Is any of this true? Carmen’s explanation for why bears attack, the Boothes’ justification for feeding them just this once?

Mostar looked about to burst. I could see the shift, the boiling rise. No more consensus building, no more playing nice. I remember thinking clearly, Oh shit, here we go.

But then the craziest thing happened.

Her face. I’d never seen this expression. Drooping, eyes down and to the side, like she was taking a call from someone in her head. This was all new, totally indecipherable. When she refocused on the room, her voice, I’d never heard it so far away.

“All right then, let’s get to it.”

And her walk afterward. Slow, dragging. Everything about her. Like God had hit the dimmer switch.

She walked right past us, not acknowledging Dan’s “Mostar?”

No one seemed to notice her change but us. Why would they? Rushing off with their new, exciting little project. Always looking out for themselves. Our community.

Except Pal. Her worried eyes shifted from me to Mostar as her parents led her away.

“Mostar?” We followed her to her house. I’d called after her this time, and again when she reached the front door. “Mostar, what’s the matter?” As she reached for the knob, I put my hand on hers. That seemed to snap her out of it. Eyes again refocused, looking up at me, hand on my cheek.

“I’m sorry, Katie. And you too, Danny.” A quick glance around at the dispersing crowd, then hustling us into and through her house to the backyard.

“I’m sorry I didn’t warn you first about the ‘bear’ tactic.” We were standing on her back steps now, looking at the tracks across her yard. “I thought it was the best way to reach them. Frame the discussion in something more familiar.” She stepped down onto the ash, toward the nearest footprint. The sky had been clear all day and night and these prints were as sharp as when they’d been made. She opened her hands to the first one, looking at us.

“Of course, I believe you, but they wouldn’t. Too many mental hurdles. Believing the unbelievable.” She shook her head. “Like being warned that the country you’ve grown up in is about to collapse, that the friends and neighbors you’ve known your whole life are going to try to kill you…” She sighed deeply, hands up to the sky. A flash of anger. “Denial. Comfort zone. Too strong. And who are any of us to judge them?”

I certainly wasn’t. I would have given anything to stay in my comfort zone. Even now, when Mostar mentioned the enigmatic trauma of her past. I could have asked about it, just like I could have asked all the other times she’d brought it up. But I didn’t. I just stood there, hoping she’d change the subject, then wishing a second later that she hadn’t.

“People only see the present through the lenses of their personal pasts.” Her lips soured. “Maybe that’s my problem too.”

She sat down on the steps, focusing on the ash. “Violence. Danger. That’s my zone of comfort.”

She looked up at us again. “You probably thought I was crazy that first night.” Her head jerked toward our house and, I’m guessing, our garden. “But I knew what I was doing. I know how quickly society can burn. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived through it. But this…”

Eyes back to the footprints. “These may be real.” Head up to the trees. “They may be out there.”

“They”? Not “it”?

“But how do I know that they’re dangerous?” She shook her head. “I don’t. They might be friendly. They might just be passing through. And the fight with that big cat. How do I know it wasn’t self-defense or that Vincent’s not right about scavengers? I don’t.”

And then I understood what had come over her. And it chilled me.

Doubt.

“Bear spray.” She huffed. “That was just the start. You don’t know how far I would have taken you all today if the others hadn’t stopped me. And maybe they were right to do so.” Her eyes, meeting ours. Apologetic? “Do I have any evidence that they’re threatening, any proof of anything except”—she blinked, hard—“the lens of my personal past?”

I couldn’t take it anymore. I still can’t. It’s been a couple hours since Mostar told us to go home. We haven’t seen her since. Dan’s off to work, brushing the Perkins-Forster roof. I’ll meet him over there after I’ve done some gardening. Not much really to do. The seeds are all in, even the rice now, scattered over a square-foot patch with some soil thrown over it. The drip line works great, so there’s no need to hand water anything. Not that anything’s coming up. Basically, my “gardening” consists of looking over a room full of mud.

I should probably go check on Mostar first. I feel so bad for her, and, yes, scared for the rest of us. We’re depending on her, Dan and I, and the whole village, whether they know it or not. We can’t have her doubting herself, ending up as lost as the rest of us. We need her to be strong. We need her to be right.

But in this case, with those things out there, what does it mean for all of us if she is?

From my interview with Frank McCray, Jr.

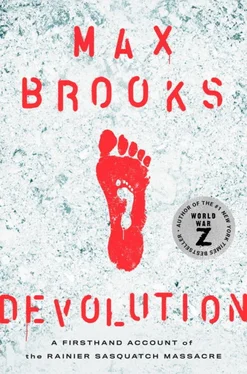

Yeah, I’ve read The Sasquatch Companion, and for the most part, I agree with the official origins story. I think the book makes some good points about being descended from Gigantopithecus and the migration from Asia to the Americas. But co-migration? I’m not so sure.

Now, I don’t have a shred of evidence to back this up, so if you want to nail me on that, be my guest. But given what happened to Greenloop, what if… what if… they weren’t just co-migrating along with us? What if they were hunting us? Isn’t that why we came over? Following the grazing animals across the Beringian land bridge? What if we were stalking the caribou while they were stalking us? It wouldn’t discount any of the adaptations, just give them a different purpose. Nocturnal hunting would catch us at our most vulnerable. Camouflage skills are ideal for an ambush. And broad running feet would give them the speed to chase us down.

And when they caught us… if the stats are right, then we’re talking about three times the strength of a gorilla, which is already six times stronger than us. And that large head, the same conical shape we see on gorillas, that’s a sagittal crest, the skull plate that anchors their jaw muscles. Those muscles give a gorilla one of the most powerful bites in the world, thirteen hundred pounds per square inch. Now triple that in a Sasquatch and picture what it would do to our bones.

Maybe they used that bite, and strength, and speed to compete with us for food, or maybe we were the food. You’ll have to talk to Josephine Schell about that part. She knows more about carnivorous apes than me.

But for whatever reason, we were the ones, not them, who couldn’t wait to flee into this vast new continent. And what if enough time went by for us, this weak little species, to build up our numbers, and our confidence, to eventually challenge the larger primates for dominance of North America? What if that’s why they’ve remained so elusive, because they knew what would happen if they stepped out of the shadows? They saw what we did to the saber-toothed cat, the dire wolf, the giant bulldog bear. They saw what we did to enough of them to realize that they were on the wrong side of evolution.

At least until Rainier.

Josephine Schell thinks I’m going too far. She’s all about ecosystems and caloric needs, and maybe she’s right. But maybe there was also some latent gene that woke up in those creatures when they stumbled across Greenloop and found themselves facing a herd of cornered, isolated Homo sapiens. Maybe some instinct told them it was time to swap evolution for devolution, reach back to who they were to reclaim what was theirs.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)