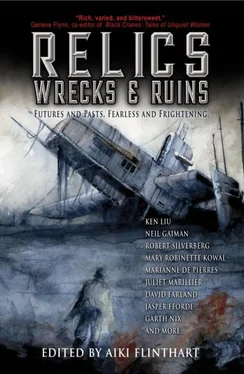

RELICS, WRECKS & RUINS

2020 Anthology of short Sci-fi, Fantasy, and Horror works

By some of the world’s best authors

Edited by Aiki Flinthart

Heartfelt thanks goes to my wonderful, supportive, fun-loving husband and my loyal, huggable, strong son. Huge appreciation to Gene Flynn, Lauren Daniels, and Pamela Jeffs who helped and supported me every step of the way in this madness. Thanks to Daniele Serra who kindly donated the beautiful cover illustration.

Also to all the authors in the Springfield Writers Group, for their enthusiasm & support; and to my many wonderful family and friends who are helping me through this difficult time.

Big thanks to Jonathan Strahan, without whose help I would not have been able to pull this crazy project into shape.

And to Ellen Datlow for her kindness and direction. And Dirk for his encouragement.

This anthology is likely to be my last project before I head off to Valhalla. So I’m hoping it will bring to your attention, dear reader, several new authors as well as let you relax with several old friends.

When you finish, if you enjoyed it, please leave a review on Goodreads or your ebook retailer so others can find it as well.

Never be afraid to try to achieve your goals. You’ll only regret it if you don’t try.

This collection contains both US and some Australian/British colloquialisms and spelling variations.

DON’T PANIC

Washing the Plaid

By Juliet Marillier

The Bridge House is a wreck. It’s been empty for years, and it’s old and crumbly and falling apart. When I walk past on the way to the school bus, I can see peeling paint and cracks in the walls. The wooden porch sags and the front door is faded to a weird shade of gravestone gray. The garden’s a mini-jungle of rioting weeds, half-dead in the end-of-winter cold.

So, everyone’s surprised when the house finally goes up for sale, then super-surprised when it sells almost immediately. The biggest shock is when Mrs. Mac moves in. That’s what people call the old lady. It’s short for Mac-something.

“Why on earth would an old girl like her buy such a huge place?” my mother asks one night at dinner. “It’ll cost a fortune to fix.”

Mum’s an accountant so everything is about budgets and money. I ignore her and flip the page of my book.

She frowns. “And Mrs. Mac must be eighty at least. Living on her own with all those dogs—that’s crazy. What if she trips over one of them and breaks her leg? Or forgets she left a pot on the stove and sets the place on fire? Mr. Briggs next door won’t be happy if they make a nuisance of themselves. He’s always hated dogs.” She points at my plate. “Rachel, close that book and finish your dinner. No reading at the table, remember?”

“If there was a fire, wouldn’t the dogs bark?” I don’t really want to be part of the conversation. I’m only here because Mum expects us all to sit at the table for meals. But someone should stand up for Mrs. Mac. “And we’d smell the smoke.” We live directly opposite the Bridge House.

“Would’ve been a smart buy for a developer.” Dad’s off on his own train of thought as usual. “That’s prime riverfront land. Demolish the old house, build a luxury two-story place, maybe a private jetty. You’d make a healthy profit. That’s if you could get around the heritage guidelines. The owner should have got us to handle the sale.” Us meaning the business he and my uncle run: Premium Property. He pauses to shove a forkful of spaghetti in his mouth, chews, and swallows. “Still, she’s an old woman,” he says. “I suppose it’ll be up for sale again before long.”

I imagine a gleaming modern house sitting there on the riverbank like some alien craft that’s landed among the big old gum trees, knocking quite a few of them over. A private jetty would mean we couldn’t walk along the riverbank anymore. It would block the path for other things too—wallabies, lizards, water birds, all the creatures that live in that patch of bushland. It might send them up onto the road where they’d get squished by passing traffic.

A house like that would never belong.

I finish my spaghetti in silence. Mum and Dad have changed the subject to some cocktail thing they’re attending on Saturday, and they’re working up to an argument. That happens a lot these days. James and I exchange a glance and take ourselves off to the kitchen. We wash and dry the dishes. In the dining room, Mum has gone quiet while Dad gives one of his lectures.

James goes up to his room, in theory to do his homework. I retreat to mine and shut the door so James can’t sneak in. He loves snooping and solving pretend crimes.

I’ve got homework, too. More than James, since he’s still at Ashburn Primary and I’m in my second year at high school. But all the talk about Mrs. Mac has given me an idea for the next part of my story and I need to write it down before it slips out of my mind. Ideas do that sometimes; like when you have a fantastic dream and then you wake up and for a moment it’s still there, bright and clear, but just fades away. That’s so cruel.

I write and write. I don’t stop until I hear Mum coming up the stairs. My neck hurts and my fingers are all cramped and it’s dark outside. I’ve written six hundred words without even thinking, as if something was sitting on my shoulder or, even creepier, in my head, controlling the whole thing. I like it when that happens; that’s when I do my best work.

But I can’t check it over now because Mum’s knocking on the door. She barges in without an invitation.

I hide my story behind a French translation assignment on the screen. I’ve never let anyone read my work. My real work, I mean. I’ve written stuff for English at school and earned high grades for it. Teachers have suggested I might do creative writing at university. But Dad wants me to work for the business, and Mum thinks I should try to get into law.

Before Mum can say, Finished your homework? something outside catches her attention. She walks to the window and stares down into the street. There’s a light out there, not the whitish streetlight but more of a gold glow, moving about.

“What’s that?” she asks.

Mum’s gazing in the general direction of Mrs. Mac’s place. I look over her shoulder, remembering the comment about pots on the stove. My eyesight is better than hers. The warm light comes from a torch. Holding the torch is the small, shadowy figure of Mrs. Mac with a shawl around her shoulders, a woolly hat on her white hair, and trainers on her feet. Beside her pads the biggest of her dogs. Its head is nearly up to her shoulder. After she moved in, I looked up dog breeds, and that one’s a Scottish deerhound. You don’t see many of those being walked around Ashburn.

“Mrs. Mac,” I say. “Just walking the dog, I guess.” Maybe two dogs; I think I spotted a tiny one tucked into her shawl, like a baby in a sling. Perhaps that one can’t walk very well.

Mrs. Mac goes in her gate with the deerhound alongside. The gold light bobs about for a bit, then cuts out as she enters the house.

“I don’t know,” mutters Mum. “Out walking in the dark, all on her own…” Her tone changes. “Finished your homework? It’s getting late.”

“Not much more to do. Half an hour, tops.”

Mum looks at her watch and rolls her eyes. “Don’t forget to iron your school shirt for tomorrow.”

“I’ll do it in the morning.”

“Rachel.” She uses the warning voice. I hate that. It’s like a threat: Do it or else (insert horrible thing that might happen). I’ve tried to explain how important my writing is, but she just doesn’t get it.

Читать дальше