She broke into a loud laugh. ‘Just listen to yourself. Your fiancée, the woman you love, and whom you want to marry and have kids with, is threatening to slit a child’s throat and your first thought is how you can clean up after her.’

He looked at her in disbelief. ‘Tell me, are you bluffing?’

‘Only partly,’ she said. ‘I still feel really tempted, but it was interesting to hear your reaction.’

He blinked. ‘Sorry, but just who is it standing there with the knife? I mean, I’m the one with more reason to be concerned.’

She looked at him with a pained expression on her face. ‘I just want all this to stop.’

‘So do I,’ he said.

‘So we agree? Can you forgive me?’

‘Always,’ he said.

‘Good,’ she said and laid the knife down.

The boy turned around in the doorway. He hadn’t said anything since he got up from the table and went out into the entryway.

‘Thanks,’ he said.

‘For what?’ she said.

‘Your generous contribution.’

Neither of them had any desire to know what he meant by that.

‘The pleasure was all yours,’ he said to the boy.

That was meant as a sarcastic comment, an ‘I-got-the-last-word’ reply, but he could himself hear how lame it sounded.

‘Farewell,’ she said.

The boy just smiled and went down the garden path. They remained standing in the doorway and watched him go, as if to assure themselves that he had entirely disappeared from their life. Only when they could no longer see him did they close the door and lock it.

They looked at each other.

‘Did we win?’ she asked.

‘I hope so,’ he said.

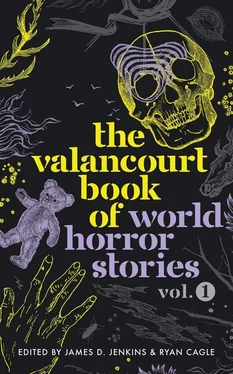

Translated from the Danish by James D. Jenkins

Solange Rodríguez Pappe

TINY WOMEN

Born in Guayaquil, Ecuador in 1976, Solange Rodríguez Pappe is a professor and an award-winning writer whose work often incorporates elements of the supernatural, strange, or macabre, usually mixed with a dose of quirky or offbeat humor. ‘Tiny Women’ originally appeared in her 2018 collection La primera vez que vi un fantasma (The First Time I Saw a Ghost) and was also selected for inclusion in the 2019 anthology Insólitas , which collected the best fantastic tales by contemporary women writers from Spain and Latin America. We fell in love with this odd little story the first time we read it, and though it’s perhaps not a ‘horror’ story in the traditional sense, we nonetheless thought it was a perfect fit for this volume, and we’re confident our readers will enjoy it as much as we did.

As I filled box after box with rubbish taken out of my parents’ house, I saw the first tiny woman run to the sofa and scamper away under its legs with a shout of euphoric joy. Nor did it surprise me overly much to stumble upon her. Being the daughter of a couple of hoarders who had done nothing else their whole life except stockpile empty paper bags, plastic containers and porcelain bugs increases the possibility that, if you make a thorough exploration, you’ll run across very strange things hidden in your childhood home.

One of my favorite activities during my boring childhood was rummaging through the contents of boxes, but challenging myself to leave things exactly as I had found them. Thus, I came across a collection of keychains from the Second World War, some pornographic coasters, and the silver dagger that my father guarded jealously underneath the slats of the bed. ‘You’ve been messing with things!’ my mother would shout if she noticed some slight rearrangement of one of the hundreds of collected objects. Then she would give me some good open-handed slaps or a stroke of her belt across my palms. ‘Learn from your brother, who never gives us any trouble.’ Obviously, since for as long as I could remember Joaquín had spent all his time playing in the street, with his toy cars, his bicycle, his skates, his gang, his little girlfriends. He had always refused to be one of the many gadgets in my mother’s collection.

Once they were in the retirement home, my parents wouldn’t need anything more than what was essential, so I had spent almost a week separating into piles what I would donate to charity, what I would give away, sell and auction at a good price, and also what I was going to hold onto. But first I had to get rid of all the filth. Amidst all the junk in the kitchen I found several lizards, a rat, and even a dead bat. If I thought about it carefully, the rat even appeared to be the corpse of an old hamster we lost in my childhood. As I was chasing some spiders with a shoe, I saw the tiny naked woman cross the living room in full war cry. Between all the odd things I was discovering there, a wild little woman running around didn’t seem all that incredible.

I looked under the seat and, just as I had imagined, there was an entire civilization of diminutive women making their life. Some were seated in groups close together, combing each other’s hair, telling each other things and laughing; some others were reclining, smoking pieces of leaves torn from a fern near the sofa; and others were entwined in wars of pleasure, licking each other’s genitals and breasts by turns, as they bit the fingers of each other’s little hands or let out sharp groans of delight. These exercises I’m telling you about, they did them in general view of the entire population without shame or modesty. I didn’t see children or pregnancies among the tiny women, who were all young and slender. All of which seemed rather hedonistic to me, not to say indecent.

In mid-afternoon the phone rang. I answered with a mixture of courage and dismay at the tiny women who were now making my cleaning of the room difficult. It was my brother Joaquín, who was asking me for a place at the house to spend the night because his wife had thrown him out again.

‘She figured out that I hadn’t broken things off with Pamela like I promised her. You know that Mom always gave me a hand with this kind of thing and let me sleep on the sofa.’

‘I’m tidying up the house, everything’s a mess and covered in dust. But if you think you can stand it, then come.’

‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what it is about that sofa, but it always makes me sleep well.’ Then I felt a shiver go up my spine.

Armed with a broom I went to sweep the tiny women’s city. With the strength of my few kilos, I turned over the seat and, when it was upside down, with swipes of the broom like an expert housewife killing crawling insects, I dispersed, shook up, and killed those that I could. It wasn’t easy. They stood their ground and they had sharp little teeth; but in less than an hour I had evicted them from the sofa. One or two fled towards the bedrooms, but I was sure that it had only been a small number in comparison with those I had eliminated. Just when I had replaced the piece of furniture in its original position, the doorbell rang. Joaquín smiled at me charmingly like Clark Gable from the other side of the peephole. Together we put the trash bags full of tiny women out on the curb so that the garbage truck could collect them.

We made a quick dinner out of some leftover soup. From time to time my glance would turn towards the floor to see the occasional tiny woman running around as she pulled her hair or wept with her mouth open, wandering aimlessly. But I managed to ignore them while my brother recounted for me the details of his sophisticated life as adviser to a politician, about the trips he was taking, the people he knew, while I discreetly kicked at the tiny women who were trying to climb up my leg.

‘I don’t want to have to choose any one woman because the impression I have is that they would rather me choose so they’ll have an excuse to start a fight. For women, men are just one more motive for their war, and no: I refuse to play that game. I’m happy with the two, the three, with the four women in my life,’ and I feigned an itch on my leg to scare a tiny woman who was vengefully sticking an arrow into my knee. Yes, Joaquín was awful, he had taken a philosophic stance towards his persistent infidelity. I thought that, I didn’t say it. Instead I smiled at him with an expression much like pleasure. Like Mom used to.

Читать дальше