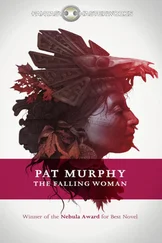

While I was thinking that, Nakaytah gathered herself and tottered toward the edge of the power circle, her hands outstretched for balance.

One thing Virissong told me was true: it was Nakaytah’s blood that brought down the circle. She fell toward it, strength draining from her body, and with a hiss and a spatter the shielding came down. Even she felt it, and through her, so did I, a buzz of power shorting out, like a circuit breaker flipping. It knocked her askew, and she sprawled across the circle’s line, landing on her back so that she and I together watched Amhuluk come smashing down to close its massive jaws over Virissong. I saw a fang slash through his right arm, and another bite through his torso, just where he’d shown me the scars that he’d claimed Nakaytah had caused. Which, technically, I guessed she had.

“Wakinyan,” Nakaytah croaked. “We need you.”

For the second time in as many moments, liquid gold burst forth from my chest and I turned inside-out.

Minutes of memory-surfing meant nothing to the world outside: no more than a blink of time had passed when I resurfaced from the thunderbird’s memories. And they were the thunderbird’s memories, I realized. Powerless or not, Nakaytah’s plea and her blood had made the creature’s passage into the Middle World possible, a dying wish granted by the very gods themselves. Her memories had played in such vivid, inhuman color because the thunderbird had partaken of the gift she offered, just as it’d gobbled through me in the skies of the Upper World. We were all in this together, shaman, spirit, and mortal alike.

I folded my wings back and tucked my claws up, plunging through the thick atmosphere. My eyes had no tears in them as wind ripped by, a thin membrane shuttering over red pupil as protection from the speed. Color dimmed only slightly with the membrane, but my focus changed, telescoping in on the serpent beneath me, its writhing form the only matter of importance in my world.

Its stubby wings drove it upward in short, twisting bursts as it strove to reach me, its Enemy, in turn. I could sense fury and hatred pouring off it, helping to fuel its passage through the sky, and knew as long as I kept it angry I had the advantage. It was in the lake below that it would come into its own, where its long serpentine form would play in and out of the water with ease while I struggled with the weight of liquid on my wings.

Backwinging, claws extended, shocked me with the force of gravity denied. It tore my breath away, making me want to laugh, wide-eyed, like a child, but the thunderbird was in control, and it had no time for my youthful glee. Wind slammed against the undersides of my wings, supporting me as my claws pinched into—no, around—the serpent’s body. Irritation surged through me, that I hadn’t drawn blood, but even so, I had the thing in my talons and flung myself skyward, wings crashing heavily against the air.

The monster in my claws twisted and struck, spires on its back rigid with rage. One bite landed and I screamed as venom shot through the wound. The sound shattered the thickness of the air, cracking the sky with its strength. I released the serpent, watching it fall away beneath me, struggling to keep aloft with its vestigial wings. I struggled as well, burning heat of poison cauterizing my blood. As a bird I had no jaw to set, but the same feeling of resolution washed through me. The bite had to be ignored, and the Enemy defeated. I turned on wingtip again, and thought, rather incongruously, hey .

Hey . I was a healer.

Hey . I had something the spirit creature didn’t.

Water in the gas line. The idea came easily, silver-sheened power rising through me even though my body wasn’t my own. I wondered briefly where the hell my body was , and if it was alive, because I didn’t see how I could’ve actually shape-shifted into a gigantic bird. The mass equation just wouldn’t work, even taking hollow bones into account. Then my heartbeat faltered as the first of the tainted blood came to it, and I stopped fucking around with little details like physics and started worrying about staying alive.

It would have been easier with a siphon, but I couldn’t wrap my mind around the idea well enough to make it work. Hell, it would’ve been easier if I could see what I was doing, but I didn’t think asking the thunderbird to nip in for a quick landing so I could step out of its body and take a look inside it would go over well.

Instead I clung to the idea of water in the gas line, one liquid floating on top of the other. Blood below, poison on top: I could tell when it began to work because the pain intensified, pure venom corroding the vessels and veins it touched. I figured the next few seconds might make me a little dizzy, but as the thunderbird folded its wings and went into another dive, it seemed as good a time as any to risk it.

It took pressure to squeeze the poison out, like a thin tube with a semisolid matter in the bottom, the liquid on top squishing its way forward. I was right: dizziness crashed through me, and instead of diving I suddenly realized I was just plain falling. The thunderbird’s heartbeat hung motionless for a terribly long time as I squeezed water from the gas line with all my concentration.

And then the poison was gone and the thunderbird somehow managed to pull out of its plummet, smashing into the serpent with such force that we all tumbled down toward the lake, tangled together. I flared my wings, slowing the fall as best I could, while the serpent wrapped itself around me, trying to crush my wings back to my body. It reared its head back, jaws agape, and lunged forward again.

To hit thin silver shielding that sparked and lit with its contact. Snakes weren’t normally much for expression, but as it flinched back I was sure I saw astonishment in its eyes. I let out a cackle of sheer delight. It erupted from my throat as a skree, making the air around me seem to collapse again.

I tore at the serpent’s face with my beak, and as it twisted away, rolled onto my back. Panic shrieked through me, warning me of my vulnerability, but it loosened the serpent’s coil from around most of my body. I rolled again, dug my claws into the Enemy’s belly, snatching it out of the air, and climbed for the sky again.

There was no sunlight left. Thick heavy clouds filled the air, like all the muggy heat of the last several days had finally coalesced together. It was my weather, thunderbird weather, and I felt the bird’s thrill of pleasure as we dragged the serpent into the clouds. Its fragile wings would be easy to rip off, its unprotected belly simple to tear open. The steaming entrails would be a feast.

I gagged. I didn’t even know birds could gag. No, I guessed they could, because mommy birds gagged up dinner for baby birds. I felt badly for the baby birds. Swallowing bird bile was not high on my list of things to do again. At any rate, I was sure eating snake was a fine thing for a bird to do, even a thunderbird, but I needed to do more than that. The coven, with my help, had opened up the passage for not just Amhuluk, but for all manner of creatures that were probably wreaking further havoc on an unsuspecting Seattle. I needed to undo that, or nothing was ever going to get straightened out. I swallowed against bile again, and tried my hand—or throat—at speaking a word with a bird’s voice box.

It came out like thunder. Amhuluk, the serpent’s name, the one I hoped was true and would force it to answer all the way from the depths of its being. Nakaytah, three millennia dead, had offered up the tool I needed to capture the thing and drag it, kicking and screaming, back into the Lower World.

Wriggling and screaming , said the snide little voice at the back of my mind.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу