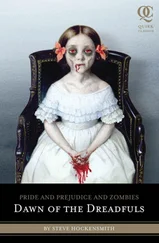

“I HAVE BEEN THINKING it over again, Elizabeth,” said her uncle, as they drove from the town; “and really, upon serious consideration, I am much more inclined than I was to judge as your eldest sister does on the matter. It appears to me so very unlikely that any young man should form such a design against a girl who is by no means unprotected or friendless, and who was actually staying in his colonel’s family, that I am strongly inclined to hope the best. Could he expect that her friends would not step forward? Could he expect that her sisters would not pursue him to the ends of the earth with their swords? Could he expect to be noticed again by the regiment, after such an affront to Colonel Forster? His temptation is not adequate to the risk!”

“Do you really think so?” cried Elizabeth.

“Upon my word,” said Mrs. Gardiner, “I begin to be of your uncle’s opinion. It is really too great a violation of decency, honour, and interest, for him to be guilty of. I cannot think so very ill of Wickham. Can you yourself, Lizzy, so wholly give him up, as to believe him capable of it?”

“Not, perhaps, of neglecting his own interest; but of every other neglect I can believe him capable. If, indeed, it should be so! But I dare not hope it. Why should he fire upon the Colonel if that had been the case?”

“In the first place,” replied Mr. Gardiner, “there is no absolute proof that they do not intend to marry.”

“But why all this secrecy? Why any fear of detection? Why must their marriage be private? Oh, no, no-this is not likely. His fellow officer, you see by Jane’s account, was persuaded of his never intending to marry her. Wickham will never marry a woman without some money. He cannot afford it. And what claims has Lydia-what attraction has she beyond youth and good length of bone that could make him, for her sake, forego every chance of benefiting himself by marrying well? As to your other objection, I am afraid it will hardly hold good. My sisters and I cannot spend any substantial time searching for Wickham, as we are each commanded by His Majesty to defend Hertfordshire from all enemies until such time as we are dead, rendered lame, or married.”

“But can you think that Lydia is so helpless as to allow herself-nay, her family to be so dishonoured?”

“It does seem, and it is most shocking indeed,” replied Elizabeth, with tears in her eyes, “that a Bennet sister’s mastery of the deadly arts should admit of doubt. But, really, I know not what to say. Perhaps I am not doing her justice. But she is very young; and for the last half-year, nay, for a twelvemonth-she has been given up to nothing but amusement and vanity. She has been allowed to dispose of her time in the most idle and frivolous manner, and to neglect her daily sparring, meditation, or even the simplest game of Kiss Me Deer. Since the Militia were first quartered in Meryton, nothing but love, flirtation, and officers have been in her head. And we all know that Wickham has every charm of person and address that can captivate a woman.”

“But you see that Jane,” said her aunt, “does not think so very ill of Wickham as to believe him capable of the attempt.”

“Of whom does Jane ever think ill? I have seen her cradle unmentionables in her arms, apologising for taking their limbs, even as they tried to bite her with their last. But Jane knows, as well as I do, what Wickham really is. We both know that he has been profligate in every sense of the word; that he has neither integrity nor honour.”

“And do you really know all this?” cried Mrs. Gardiner.

“I do indeed,” replied Elizabeth, colouring. “I told you, the other day, of his infamous behaviour to Mr. Darcy; and you yourself, when last at Longbourn, heard in what manner he spoke of the man who had behaved with such forbearance and liberality towards him. And there are other circumstances which I am not at liberty-which it is not worth while to relate; but his lies about the whole Pemberley family are endless.”

“But does Lydia know nothing of this? Can she be ignorant of what you and Jane seem so well to understand?”

“Oh, yes! That is the worst of all. Till I was in Kent, and saw so much both of Mr. Darcy and his relation Colonel Fitzwilliam, I was ignorant of the truth myself-so ignorant that my honour required the seven cuts. And when I returned home, the Militia was to leave Meryton in a week or fortnight’s time. As that was the case, neither Jane, to whom I related the whole, nor I, thought it necessary to make our knowledge public; for of what use could it apparently be to any one, that the good opinion which all the neighbourhood had of him should then be overthrown? And even when it was settled that Lydia should go with Mrs. Forster, the necessity of opening her eyes to his character never occurred to me.”

“When they all removed to Brighton, therefore, you had no reason, I suppose, to believe them fond of each other?”

“Not the slightest. I can remember no symptom of affection on either side, other than her carving his name into her midriff with a dagger; but this was customary with Lydia. When first he entered the corps, she was ready enough to admire him; but so we all were. Every girl in or near Meryton was out of her senses about him for the first two months; but he never distinguished her by any particular attention; and, consequently, after a moderate period of extravagant and wild admiration, her fancy gave way, and others of the regiment, who treated her with more distinction, again became her favourites.”

However little of novelty could be added to their fears, hopes, and conjectures, on this interesting subject, by its repeated discussion, no other could detain them from it long, during the whole of the journey. From Elizabeth’s thoughts it was never absent. Fixed there by the keenest of all anguish, self-reproach, she could find no interval.

They travelled as expeditiously as possible, until they neared the village of Lowe, where there had lately been a skirmish between the King’s army and a southerly herd. Here, the road became so littered with bodies (human and unmentionable alike), that it was rendered almost impassable. As the bodies were unsafe to touch, the coachman was forced to lift the iron beak from the undercarriage and affix it to the horses-hanging it with leather straps from their necks, so that it rested front of their feet, forming a plow, which pushed the bodies aside as they continued.

Determined that they should lose no more time, Elizabeth sat next to the coachman with her Brown Bess, ready to meet the slightest sign of trouble with the crack of powder. She ordered him to stop for nothing; even that most personal business would have to be attended to from where they sat. They drove through the night, and reached Longbourn by dinner time the next day. It was a comfort to Elizabeth to consider that Jane could not have been wearied by long expectations.

The little Gardiners, attracted by the sight of a chaise, were standing on the steps of the house as they entered the paddock; and, when the carriage drove up to the door, the joyful surprise that lighted up their faces was the first pleasing earnest of their welcome.

Elizabeth jumped out; and, after giving each of them a hasty kiss, hurried into the vestibule, where Jane immediately met her.

Elizabeth, as she affectionately embraced her, whilst tears filled the eyes of both, lost not a moment in asking whether anything had been heard of the fugitives.

“Not yet,” replied Jane. “But now that my dear uncle is come, I hope everything will be well. Oh! Lizzy! Our sister abducted and repeatedly dishonoured, even as we stand here helpless!”

“Is my father in town?”

“Yes, he went on Tuesday, as I wrote you word.”

Читать дальше