And when the phone rang again and footsteps came down the hall towards my room to give me a message, it wasn't from my brother.

Someone else entirely had sent the message. The nonsense one about fishing and leaves, and water under the bridge.

It wasn't my brother. Of course not.

But the nurse said it was, and left the message on my bedside table.

Bear and I stared at it for most of the night, wondering if the world had gone quite mad.

***

My flat-mate came to visit the next day.

I found out the most amazing thing: it's catching.

She, it seemed, saw ghosts now too. My parents, my sister-she saw them all.

Oh, the long conversations she'd had with them, face to face.

I told my doctor he should write it up. The second sight is a communicable disease. It would make his name.

We'd be famous. All of us.

***

She did her best, my flat-mate. But she smiled too much.

I offered her some vodka, she certainly looked like she needed it, but they must have taken my bottle away, because the drawer was empty.

Or, I'd drunk it all.

"I feel like I've downed a whole bottle," I said.

She smiled. Too much.

And then she said: "Your brother rang. He sends his love."

Whoever she was went away, then, and it was me and the bear and a nurse looking jolly and worried, and fuck them all, really, apart from the bear.

He just stays quiet, like people should.

None of this shit about messages. None of this sending of love, which really means: "You really must come and stay with us for Christmas."

But it sounds so cold and far away, where he lives.

So I'll try to hang on. I'll try not to go.

We'll try to hang on together, won't we, bear?

***

But the furry brute's silent.

And the river is rising and Christmas is coming.

And I guess I really should go.

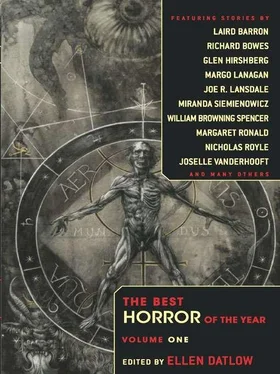

Sweeney Among the Straight Razors by JoSelle Vanderhooft

(after T. S. Eliot)

Switchblade Sweeney sweeps his floors-

grey curls and stubbly foam, stray molars'

snaggle roots, their pitted tops decayed

down to the stringing pulp. He hums

balladeer;

Scarborough Fair, Greensleeves,

lampblack hair bound back to scrub and scour,

lips summer-chapped, eyes sleepless-rubbed, but clear.

The nightingales are singing in the eaves

and from the shop below, the swirl of starch

the onion sting and clink of ale, the chop

chop chop of carrot, shell of peas.

The unmistakable waft of oregano.

On palm and knee he pigeon-picks each hair,

each fleck of flesh, each shred of cuticle,

a writhing leech replaced in her glass bowl.

So much work to be done with surgeon's care

he near forgets the bigger mess-the man

ash-cheeked, exsanguinate, distressed

upon the chair. His fingers cramped to claws

even in death. The blood spreads everywhere.

Straight-edged Sweeney sighs like bakehouse smoke

and dips his rag into the lavabo.

The water drizzles gristle-like the pulp

that Mrs. Lovett folds into her pies.

Hair, teeth and surgery; the little things

school one in patience and respect. The way

the razor pares the flesh, the fallow bones

blasted from age and bodily neglect;

musculature of thorax, thigh and back;

mucous-machinery of myelin;

gut avenues beneath the stomach trap;

ghost lungs that in their silence lie

like lovers in dread of discovery.

The steel-jawed barber wonders, what is man,

(steadily as he carves), but sallow skin

gilding all this gross anatomy

as truth is buttered up in flattery

and crust covers Mrs. Lovett's pies?

How easy, then, it is to slice the meat,

drop it down the shaft, fetch broom and sweep?

His work almost complete, serrated Sweeney

magpie-picks the leavings for the gruel.

The day is done, and cruel things still are cruel.

The day is done, and smoke churns from the chimney.

From bone to skin, men are monstrosities.

The nightingales sing in the laurel trees.

Loup-Garou by R. B. Russell

I first saw the film,

Loup-garou, in 1989, in a little arts cinema in the centre of Birmingham. I had driven there for a job interview and, as usual, I had allowed far more time for the journey than was required. I had reasoned that it should take me two hours to travel there, to park, and to find the offices of the firm of accountants where I desperately wanted a position. The interview was at two-thirty, so I intended to leave home at midday. I had worked it all out the night before, but then became concerned that the traffic might be against me, and I decided to allow another half-hour for the journey. That morning I checked my map, but no car parks were marked on it and so I added yet another half-hour to the time I would allow myself. Leaving at eleven o'clock seemed prudent, but I was ready by half-ten and, rather than sit around the house worrying, I decided to set out.

I know my nervousness about travelling is a failing, but I've always lived and worked in this small provincial town and it is not a day-to-day problem. On this occasion it was made very obvious to me just how irrational my fear of being late for appointments really was; the traffic was light and the roads clear and I was in the centre of Birmingham by a quarter to twelve. I found a car park with ease and was immediately passed a ticket by a motorist who was already leaving, despite paying to stay the whole day. I parked, and as I walked out on to the street I could see the very offices that I wanted directly opposite. I had two and a half hours to kill.

For no reason other than to pass the time I looked into the foyer of the cinema which was immediately adjacent to the car park. Pegged up on a board was the information that a film called

Loup-garou was about to start, and that it would be finished by two o'clock. It seemed the perfect solution to my problem.

I doubt if there were more than five or six people in the cinema. It was small and modern and the seat into which I settled myself was not too uncomfortable. I was in time to watch the opening credits slowly unfold. The sun was rising over a pretty, flat countryside, and the names of the actors, all French, slowly faded in and out as the light came up over fields and trees. It was beautifully shot, and a simple, haunting piano piece repeated quietly as the small cast were introduced, and finally the writer and director, Alain Legrand. I noted the name carefully from the information in the foyer when I left the cinema two hours later.

The film was incredibly slow, but each scene was so wonderfully framed, and the colours so achingly vivid that it was almost too lovely to watch. The sunlight, a numinous amber, slanted horizontally across the landscape as we were introduced to the hero, a boy who was walking from his home in the village to a house only a half-mile distant. The camera was with him every step of the way. There was a quiet voice-over, in French, that was unhurried enough for me to understand it. The boy was kicking a stone and noting that he had a theory that four was a perfect number, as exemplified by a square. Therefore, if he kicked this stone, or tapped the rail of a fence, he had to do it three more times to make it perfect. If, by some unfortunate mischance, he should repeat the action so that it was done, say, five times, then he would have to make it up to sixteen-four times four. The penalty for getting that wrong was huge; the action would need to be repeated again and again to make it up to two hundred and fifty-six, or sixteen times sixteen.

Читать дальше