He grins lopsidedly. “I can’t. That was one hell of a spell you got for us, Cas. I’d sure like to meet your supplier.”

“I’ll introduce you sometime,” I hear myself say. But not right now. Gideon is the last person I want to talk to, when I’ve just lost the knife. My eardrums would burst from all the yelling. The athame. My father’s legacy. I have to get it back, and soon.

* * *

“The athame is gone. You lost it. Where is it? ”

He’s got me by the throat, strangling the answers, slamming me back into my pillow.

“Stupid, stupid, STUPID!”

I wake up swinging, popped upright in my bed like a rock ’em sock ’em robot. The room is empty. Of course it is; don’t be stupid . Using the same word on myself brings me back into the dream. I’m only half-awake. The memory of his hands on my throat is lingering. I still can’t speak. There’s too much tightness, there and in my chest. I take a deep breath, and when I exhale it comes out ragged, close to a sob. My body feels full of empty spaces where the weight of the knife should be. My heart is pounding.

Was it my father? The idea brings me back ten years, and the guilt of a kid balloons sharply in my heart. But no. It couldn’t have been. The thing in my dream had a Creole or Cajun accent, and my father grew up in accent-neutral Chicago, Illinois. It was just another dream, like the rest, and at least I know where this one came from. It doesn’t take a Freudian interpreter to realize I feel bad about losing the athame.

Tybalt jumps up onto my lap. In the scant moonlight through my window I can just make out the green oval of his irises. He puts a paw up on my chest.

“Yeah,” I say. The sound of my voice in the dark is sharp and too loud. But it sends the dream farther away. It was so vivid. I can still remember the acrid, bitter smell of something like smoke.

“Meow,” Tybalt says.

“No more sleep for Theseus Cassio,” I agree, scooping him up and heading downstairs.

When I get there, I put some coffee on and park my butt at the kitchen table. My mom has left out the jar of salt for the athame, along with clean cloths and oils to rub it and rinse it and make it new. It’s out there somewhere. I can feel it. I can feel it in the hands of someone who never should have touched it. I’m starting to think murderous thoughts about Will Rosenberg.

My mom comes down about three hours later. I’m still sitting at the table and staring at the jar as the light grows stronger in the kitchen. Once or twice my head thumped down against the wood and then bounced back up again, but I’m half a pot of coffee in now, and I feel fine. Mom is wrapped in her blue bathrobe and her hair looks comfortingly fuzzy. The sight calms me immediately, even as she glances at the empty jar of salt and puts the cover back on. What is it about the sight of your mother that makes everything fireside-warm and full of dancing Muppets?

“You stole my cat,” she says, pouring herself a cup of coffee. Tybalt must sense my unrest; he’s been circling around my feet off and on, something he usually only does to my mom.

“Here, have him back,” I say as she comes to the table. I hoist him up. He doesn’t stop hissing until she brings him down to her lap.

“No luck last night?” she asks, and nods at the empty jar.

“Not exactly,” I say. “There was some luck. Luck of both kinds.”

She sits with me and listens while I spill my guts. I tell her everything we saw, everything we learned about Anna, how I broke the curse and freed her. I end with my worst embarrassment: that I lost Dad’s athame. I can hardly look at her when I tell her that last part. She’s trying to control her expression. I don’t know if that means she’s upset that it’s gone or if it means she knows what the loss of it must’ve done to me.

“I don’t think you made a mistake, Cas,” she says gently.

“But the knife.”

“We’ll get the knife back. I’ll call that boy’s mother, if I have to.”

I groan. She just crossed the mom line from cool and comforting to Queen of Lame.

“But what you did,” she goes on. “With Anna. I don’t think it was a mistake.”

“It was my job to kill her.”

“Was it? Or was it your job to stop her?” She leans back from the table, cradling her coffee mug between her hands. “What you do — what your dad did — it was never about vengeance. Never about revenge, or tipping the scales back to even. That’s not your call.”

I rub my hand across my face. My eyes are too tired to see straight. My brain is too tired to think straight.

“But you did stop her, didn’t you, Cas?”

“Yes,” I say, but I don’t know. It happened so fast. Did I really get rid of Anna’s dark half, or did I just allow her to hide it? I shut my eyes. “I don’t know. I think so.”

My mom sighs. “Stop drinking this coffee.” She pushes my cup away. “Go back to bed. And then go to Anna and find out what she’s become.”

* * *

I’ve seen a lot of seasons change. When you’re not distracted by school and friends and what movie’s coming out next week, you’ve got time to look at the trees.

Thunder Bay’s autumn is prettier than most. There’s lots of color. Lots of rustle. But it’s also more volatile. Frigid and wet one day, with a side of gray clouds, and then days like today, where the sun looks as warm as July and the breeze is so light that the leaves just seem to glisten as they move in it.

I’ve got my mom’s car. I drove it up to Anna’s place after dropping Mom to do some shopping downtown. She said she’d get a lift home from a friend. I was glad to hear that she’d made some friends. She does it easily, being so open and easygoing. Not like me. I don’t think it was quite like my dad either, but I find that I can’t really remember, and that bothers me, so I don’t push my brain too hard. I’d rather believe that the memories are there, just under the surface, whether they really are or not.

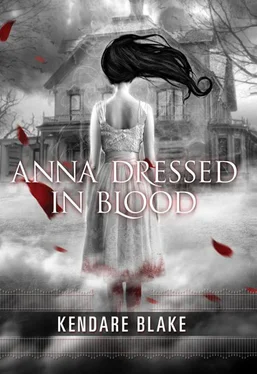

As I walk up to the house, I think I see a shadow move on the west side. I blink it off as a trick of my too-tired eyes … until the shadow turns white and shows her pale skin.

“I haven’t wandered far,” Anna says as I walk up.

“You hid from me.”

“I wasn’t sure right away who you were. I have to be cautious. I don’t want to be seen by everyone. Just because I can leave my house now doesn’t mean I’m not still dead.” She shrugs. She’s so frank. She should be damaged by all of this, damaged beyond sanity. “I’m glad you came back.”

“I need to know,” I say. “If you’re still dangerous.”

“We should go inside,” she says, and I agree. It’s strange to see her outdoors, in the sunlight, looking for all the world like a girl out picking flowers on a bright afternoon. Except that anyone looking closely would realize she should be freezing out here wearing just that white dress.

She leads me into the house and closes the door behind like any good hostess. Something about the house has changed too. The gray light is gone. Plain old white sunshine streams through the windows, albeit with a hampering of dirt on the glass.

“What is it that you really want to know, Cas?” Anna asks. “Do you want to know if I’m going to kill more people? Or do you want to know if I can still do this?” She holds her hand up before her face, and dark veins snake up to the fingers. Her eyes go black and a dress of blood erupts through the white, more violently than before, splashing droplets everywhere.

I jump back. “Jesus, Anna!”

She hovers in the air, does a little twirl like something’s playing her favorite tune.

“It’s not pretty, is it?” She crinkles her nose. “There aren’t mirrors left here, but I could see myself in the window glass when the moonlight was bright enough.”

Читать дальше