Jilly laughed. “A witch?”

That was a new one on her.

Annie waved a hand towards the wall across from the window where Jilly was sitting. Paintings leaned up against each other in untidy stacks. Above them, the wall held more, a careless gallery hung frame to frame to save space. They were part of Jilly’s ongoing “Urban Faerie” series, realistic city scenes and characters to which were added the curious little denizens of lands which never were. Hobs and fairies, little elf men and goblins.

“They say you think all that stuff’s real,” Annie said. “What do you think?”

When Annie gave her a “give me a break” look, Jilly just smiled again.

“How about some breakfast?” she asked to change the subject. “Look,” Annie said. “I really appreciate your taking me in and feeding me and everything last night, but I don’t want to be freeloader.”

“One more meal’s not freeloading.”

Jilly pretended to pay no attention as Annie’s pride fought with her baby’s need.

“Well, if you’re sure it’s okay,” Annie said hesitantly. “I wouldn’t have offered if it wasn’t,” Jilly said.

She dropped down from the windowsill and went across the loft to the kitchen corner. She normally didn’t eat a big breakfast, but twenty minutes later they were both sitting down to fried eggs and bacon, home fries and toast, coffee for Jilly and herb tea for Annie.

“Got any plans for today?” Jilly asked as they were finishing up.

“Why?” Annie replied, immediately suspicious.

“I thought you might want to come visit a friend of mine.”

“A social worker, right?”

The tone in her voice was the same as though she was talking about a cockroach or maggot.

Jilly shook her head. “More like a storefront counselor. Her name’s Angelina Marceau. She runs that dropin center on Grasso Street. It’s privately funded, no political connections.”

“I’ve heard of her. The Grasso Street Angel.”

“You don’t have to come,” Jilly said, “but I know she’d like to meet you.”

“I’m sure.”

Jilly shrugged. When she started to clean up, Annie stopped her. “Please,” she said. “Let me do it.”

Jilly retrieved her sketchpad from the bed and returned to the windowseat while Annie washed up.

She was just adding the finishing touches to the rough portrait she’d started earlier when Annie came to sit on the edge of the Murphy bed.

“That painting on the easel,” Annie said. “Is that something new you’re working on?”

Jilly nodded.

“It’s not like your other stuff at all.”

“I’m part of an artist’s group that calls itself the Five Coyotes Singing Studio,” Jilly explained. “The actual studio’s owned by a friend of mine named Sophie Etoile, but we all work in it from time to time.

There’s five of us, all women, and we’re doing a group show with a theme of child abuse at the Green Man Gallery next month.”

“And that painting’s going to be in it?” Annie asked. “It’s one of three I’m doing for the show.”

“What’s that one called?”

“‘I Don’t Know How To Laugh Anymore.’”

Annie put her hands on top of her swollen stomach. “Me, neither,” she said.

6

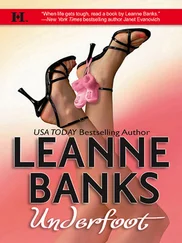

I Don’t Know How to Laugh Anymore, by Jilly Coppercorn. Oils and mixed media. Yoors Street Studio, Newford, 1991.

A lifesized female subject leans against an inner city wall in the classic pose of a prostitute waiting for a customer. She wears high heels, a microminiskirt, tubetop and short jacket, with a purse slung over one shoulder, hanging against her hip from a narrow strap. Her hands are thrust into the pockets of her jacket. Her features are tired, the lost look of a junkie in her eyes undermining her attempt to appear sultry.

Near her feet, a condom is attached to the painting, stiffened with gesso.

The subject is thirteen years old.

I started running away from home when I was ten. The summer I turned eleven I managed to make it to Newford and lived on its streets for six months. I ate what I could find in the dumpsters behind the McDonald’s and other fast food places on Williamson Street—there was nothing wrong with the food. It was just dried out from having been under the heating lamps for too long.

I spent those six months walking the streets all night. I was afraid to sleep when it was dark because I was just a kid and who knows what could’ve happened to me. At least being awake I could hide whenever I saw something that made me nervous. In the daytime I slept where I could—in parks, in the back seats of abandoned cars, wherever I didn’t think I’d get caught. I tried to keep myself clean, washed up in restaurant bathrooms and at this gas bar on Yoors Street where the guy running the pumps took a liking to me. Paydays he’d spot me for lunch at the grill down the street.

I started drawing back then and for awhile I tried to hawk my pictures to the tourists down by the Pier, but the stuff wasn’t all that good and I was drawing with pencils on foolscap or pages torn out of old school notebooks—not exactly the kind of art that looks good in a frame, if you know what I mean. I did a lot better panhandling and shoplifting.

I finally got busted trying to boost a tape deck from Kreiger’s Stereo—it used to be where Gypsy Records is. Now it’s out on the strip past the Tombs. I’ve always been small for my age, which didn’t help when I tried to to convince the cops that I was older than I really was. I figured juvie would be better than going back to my parents’ place, but it didn’t work. My parents had a missing persons out on me, God knows why. It’s not like they could’ve missed me.

But I didn’t go back home. My mother didn’t want me and my dad didn’t argue, so I guess he didn’t either. I figured that was great until I started making the rounds of foster homes, bouncing back and forth them and the Home for Wayward Girls. It’s just juvie with an oldfashioned name.

I guess there must be some good foster parents, but I never saw any. All mine ever wanted was to collect their check and treat me like I was a piece of shit unless my case worker was coming by for a visit. Then I got moved up from the mattress in the basement to one of their kids’ rooms. The first time I tried to tell the worker what was going down, she didn’t believe me and then my foster parents beat the crap out of me once she was gone. I didn’t make that mistake again.

I was thirteen and in my fourth or fifth foster home when I got molested again. This time I didn’t take any crap. I booted the old pervert in the balls and just took off out of there, back to Newford.

I was older and knew better now. Girls I talked to in juvie told me how to get around, who to trust and who was just out to peddle your ass.

See, I never planned on being a hooker. I don’t know what I thought I’d do when I got to the city—I wasn’t exactly thinking straight. Anyway, I ended up with this guy—Robert Carson. He was fifteen.

I met him in back of the Convention Center on the beach where all the kids used to all hang out in the summer and we ended up getting a room together on Grasso Street, near the high school. I was still pretty fucked up about getting physical with a guy but we ended up doing so many drugs—acid, MDA, coke, smack, you name it—that half the time I didn’t know when he was putting it to me.

We ran out of money one day, rent was due, no food in the place, no dope, both of us too fucked up to panhandle, when Rob gets the big idea of selling my ass to bring in a little money. Well, I was screwed up, but not that screwed up. But then he got some guy to front him some smack and next thing I know I’m in this car with some guy I never saw before and he’s expecting a blow job and I’m crying and all fucked up from the dope and then I’m doing it and standing out on the street corner where he’s dumped me some ten minutes later with forty bucks in my hand and Rob’s laughing, saying how we got it made, and all I can do is crouch on the sidewalk and puke, trying to get the taste of that guy’s come out of my mouth.

Читать дальше