Winds somewhere safe to sea

— from British folklore; collected by Stephen Gallagher

There were ten thousand maniacs on the radio—the band, not a bunch of lunatics; playing their latest single, Natalie Merchant’s distinctive voice rising from the music like a soothing balm.

Trouble me ....

Sharing your problems ... sometimes talking a thing through was enough to ease the burden. You didn’t need to be a shrink to know it could work. You just had to find someone to listen to you.

Nicky Straw had tried talking. He’d try anything if it would work, but nothing did. There was only one way to deal with his problems and it took him a long time to accept that. But it was hard, because the job was never done. Every time he put one of them down, another of the freaks would come buzzing in his face like a fly on a corpse.

He was getting tired of fixing things. Tired of running. Tired of being on his own.

Trouble me ....

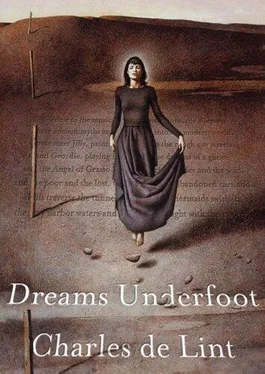

He could hear the music clearly from where he crouched in the bushes. The boom box pumped out the song from one corner of the blanket on which she was sitting, reading a paperback edition of Christy Riddell’s How to Make the Wind Blow. She even looked a little like Natalie Merchant. Same dark eyes, same dark hair; same slight build. Better taste in clothes, though. None of those thrift shop dresses and the like that made Merchant look like she was old before her time; just a nice white Butler U. Tshirt and a pair of bright yellow jogging shorts. White Reeboks with laces to match the shorts; a red headband.

The light was leaking from the sky. Be too dark to read soon. Maybe she’d get up and go.

Nicky sat back on his haunches. He shifted his weight from one leg to the other.

Maybe nothing would happen, but he didn’t see things working out that way. Not with how his luck was running.

All bad.

Trouble me ....

I did, he thought. I tried. But it didn’t work out, did it?

So now he was back to fixing things the only way he knew how.

Her name was Luann. Luann Somerson.

She’d picked him up in the Tombs—about as far from the green harbor of Fitzhenry Park as you could get in Newford. It was the lost part of the city—a wilderness of urban decay stolen back from the neon and glitter. Block on block of decaying tenements and rundown buildings. The kind of place to which the homeless gravitated, looking for squats; where the kids hung out to sneak beers and junkies made their deals, hands twitching as they exchanged rumpled bills for little packets of shortlived empyrean; where winos slept in doorways that reeked of puke and urine and the cops only went if they were on the take and meeting the moneyman.

It was also the kind of place where the freaks hid out, waiting for Lady Night to start her prowl.

Waiting for dark. The freaks liked her shadows and he did too, because he could hide in them as well as they could. Maybe better. He was still alive, wasn’t he?

He was looking for the freaks to show when Luann approached him, sitting with his back against the wall, right on the edge of the Tombs, watching the rush hour slow to a trickle on Gracie Street. He had his legs splayed out on the sidewalk in front of him, playing the drunk, the bum. Threedays’ stubble, hair getting ragged, scruffy clothes, two dimes in his pocket—it wasn’t hard to look the part. Commuters stepped over him or went around him, but nobody gave him a second glance. Their gazes just touched him, then slid on by. Until she showed up.

She stopped, then crouched down so that she wasn’t standing over him. She looked too healthy and clean to be hanging around this part of town.

“You look like you could use a meal,” she said.

“I suppose you’re buying?”

She nodded.

Nicky just shook his head. “What? You like to live dangerously or something, lady? I could be anybody.”

She nodded again, a half smile playing on her lips.

“Sure,” she said. “Anybody at all. Except you’re Nicky Straw. We used to take English 201

together, remember?”

He’d recognized her as well, just hoped she hadn’t. The guy she remembered didn’t exist anymore.

“I know about being down on your luck,” she added when he didn’t respond. “Believe me, I’ve been there.”

You haven’t been anywhere, he thought. You don’t want to know about the places I’ve been.

“You’re Luann Somerson,” he said finally.

Again that smile. “Let me buy you a meal, Nicky.”

He’d wanted to avoid this kind of a thing, but he supposed he’d known all along that he couldn’t.

This was what happened when the hunt took you into your hometown. You didn’t disappear into the background like all the other bums. Someone was always there to remember.

Hey, Nicky. How’s it going? How’s the wife and that kid ofyours?

Like they cared. Maybe he should just tell the truth for a change. You know those things we used to think were hiding in the closet when we were too young to know any better? Well, surprise. One night one of those monsters came out of the closet and chewed off their faces ....

“C’mon,” Luann was saying.

She stood up, waiting for him. He gave it a heartbeat, then another. When he saw she wasn’t going without him, he finally got to his feet.

“You do this a lot?” he asked.

She shook her head. “First time,” she said.

All it took was one time ....

“I’m like everyone else,” she said. “I pretend there’s no one there, lying halfstarved in the gutter, you know? But when I recognized you, I couldn’t just walk by.”

You should have, he thought.

His silence was making her nervous and she began to chatter as they headed slowly down Yoors Street.

“Why don’t we just go back to my place?” she said. “It’ll give you a chance to clean up.

Chad—that’s my ex—left some clothes behind that might fit you ....”

Her voice trailed off. She was embarrassed now, finally realizing how he must feel, having her see him like this.

“Uh ...”

“That’d be great,” he said, relenting.

He got that smile of hers as a reward. A man could get lost in its warmth, he thought. It’d feed a freak for a month.

“So this guy,” he said. “Chad. He been gone long?” The smile faltered.

“Three and a half weeks now,” she said.

That explained a lot. Nothing made you forget your own troubles so much as running into someone who had them worse. “Not too bright a guy, I guess,” he said.

“That’s ... Thank you, Nicky. I guess I need to hear that kind of thing.”

“Hey, I’m a bum. We’ve got nothing better to do than to think up nice things to say.”

“You were never a bum, Nicky.”

“Yeah. Well, things change.”

She took the hint. As they walked on, she talked about the book she’d started reading last night instead.

It took them fifteen minutes or so to reach her apartment on McKennitt, right in the heart of Lower Crowsea. It was a walkup with its own stairwell—a narrow, winding affair that started on the pavement by the entrance of a small Lebanese groceteria and then deposited you on a balcony overlooking the street.

Inside, the apartment had the look of a recent splitup. There was an amplifier on a wooden orange crate by the front window, but no turntable or speakers. The bookcase to the right of the window had gaps where apparently random volumes had been removed. A pair of rattan chairs with bright slipcovers stood in the middle of the room, but there were no end tables to go with them, nor a coffee table. She was making do with another orange crate, this one cluttered with magazines, a couple of plates stacked on top of each other and what looked like every coffee mug she owned squeezed into the remaining space. A small portable blackand-white Zenith TV stood at the base of the bookcase, alongside a portable cassette deck. There were a couple of rectangles on the wall where paintings had obviously been removed. A couple of weeks’ worth of newspapers were in a pile on the floor by one of the chairs.

Читать дальше