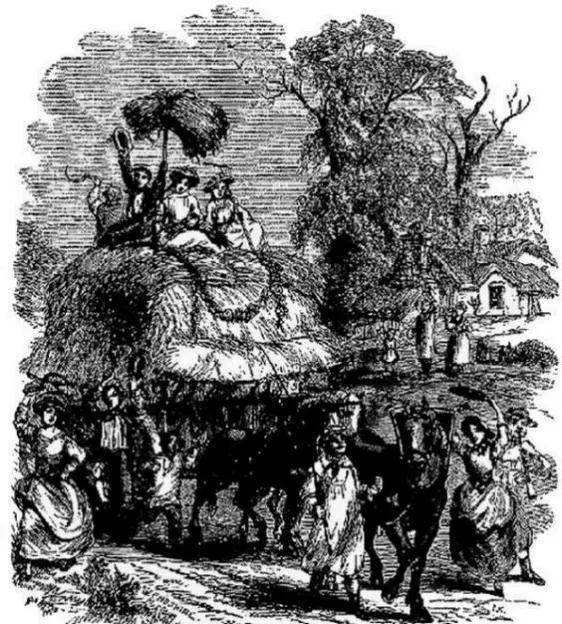

Thomas Tryon. Harvest Home

I awakened that morning to birdsong. It was only the little yellow bird who lives in the locust tree outside our bedroom window, but I could have wrung his neck, for it was not yet six and I had a hangover. That was in late summer, before Harvest Home, before the bird left its nest for the winter. Now it is spring again, alas, and as predicted the yellow bird has returned. The Eternal Return, as they call it here. Thinking back from this day to that one nine months ago, I now imagine the bird to have been sounding a warning. But that is nonsense, of course, for who could have thought it was a bird of ill omen, that little creature?

During the first long summer, its cheerful notes seemed to stand both as a mark of fulfillment and as a promise of profound happiness, signifying the achievement of our hearts’ desire. Happiness, fulfillment-if promised, they came only in the strangest measure.

The house, though new to us when we purchased it in the spring, was almost three hundred years old, an uninhabited wreck we had chanced upon, bought, and spent the summer restoring. In late August, with the greater part of the work behind us, I was enjoying the satisfaction of realizing one’s fondest wish. A house in the country. The great back-to-the-land movement. City mouse into country mouse. Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Constantine and daughter, landed gentry, late of New York City, presently residing at 11 Penrose Lane, in the ancient New England village of Cornwall Coombe. We had lived there less than four months.

I had thrown up my job as advertising executive with a large New York firm and was now working as a serious artist, painting in the studio I had made from the chicken house behind the garage. My time was my own; I kept no scheduled hours, but worked as I chose. Yet, habitually an early riser, I liked to take advantage of the pristine morning solitude, often abroad in the still unfamiliar village environs to discover a housefront to sketch, a river view, a tree, whatever might catch my fancy. Today, however, I felt slothful. Hung over, lumpish, unwilling to rise, I told myself it must be Saturday, and hoped it was true. I was dimly aware that the day held some particular significance, though what it was I could not recall.

My stomach made a hollow noise, and Beth’s head turned toward me. She reached and touched my hand, the corners of her mouth lifting with the fleeting traces of a smile; even in her sleep she knew I was suffering for my last night’s overindulgence. I tried to give her back her hand, placing it where it had rested, at her breast, but her fingers remained entwined in mine. She offered companionable little pressures between them as she lay reclined at an easy angle, tendrils of hair partly covering her closed eyes.

I listened to her easy, rhythmic breathing, watched the rise and fall of her breast, my eye lingering on the rounded fullness of the pale flesh, the darker, almost carmine-colored tips under the pleated, translucent cotton. Though pillow-creased and sleepy, a trifle wan and strained, her face to me, sixteen years her husband, was infinitely pleasing. I was not only her spouse, her lover, but her admirer as well, and I speculated as to how many married couples were as good friends as we were.

As I gazed at her, not wanting to wake her, I realized that her face was thinner. Since our coming to the village, with the work and worry of the house, and the continuing crises with our young teenage daughter Kate, fatigue had shown itself, and I wondered if having traded being city mice for being country mice was not a mistake.

She was not asleep. The smile widened lazily, her lids fluttered, she drew a luxurious breath, and opened her eyes.

“Good morning, darling.”

I smiled back and said good morning.

“Hung over?”

“Mm.”

“Poor sweet.”

A blue vein throbbed in her neck and I bent and pressed my mouth to it. Her arm came around my head, holding it there, her fingers playing in my hair. My wife, my love. She moved closer, her hand sliding down my cheek, feeling my night’s growth of whiskers. “Bluebeard,” she murmured, and I turned my head to find her lips. I kissed the sleep from her mouth and from her eyes; gentle kisses, but as her body pressed against mine I felt a stirring, a compelling surge. She must have felt it, too, for contented sounds came from behind her lips, and I pulled her nearer still. It was not our custom to make love in the morning-we had not, in fact, made love for some time-but quite suddenly, of all ideas it seemed the best and the most natural.

I waited while she disengaged herself, slid from under the sheet on her side of the bed, and stood. Splaying her fingers, she combed them through her hair and shook it out. It fell across her face again, obscuring her profile as she looked down to undo her nightgown. Sun rays filtering through the window framed her from behind, the flesh opaquely dark against the sheer white fabric, and the melting light produced a sort of corona around the sweep of her hair. She raised the shift over her head, bending to lay it aside with a grace and innocence that reminded me of one of those lovely pastel bathers of Degas.

When she put herself into my arms, she was warm and smelled of sleep and softness. I could feel the fragile cage of her ribs under the flesh of her back as she arched against me; yes, she was thinner. We made love affectionately, communicatively, tenderly, but without passion; we had become too used to each other, and to the act, for it to hold any new mysteries. Beth’s nature was not one of passion, but rather of compliancy. She was accessible, submissive, yielding in a mild, utterly feminine way. Myself, I did not dream of great passions; she was my wife, I loved her, we had a child, and though we could not have another, still we were a family. I had never been unfaithful, either in body or in spirit, and if passion was lacking, there were other things, more important things, that made up for the lack.

Later, we lay still joined, uttering satisfied resonances into each other’s necks and cheeks. I remember thinking how lucky I was, feeling safe and secure in the world we were creating for ourselves, this new world in the village of Cornwall Coombe. And this, our bedroom, seemed the very heart, the alive and throbbing, most particular and exact center of that world. Lying at peace, I let my eye rove around its already familiar, lived-in spaces, enjoying the pale buttery yellow of the simple plaster walls that took the sunlight and amplified it, the thick, creamy enameled woodwork, the matching Chippendale chests serving as bureaus, the Hudson River landscape over the fireplace, the airy curtains Beth had made, the bowl of flowers she had arranged on the mantel, her dressing table with its array of crystal bottles-perfume she seldom wore. Our room, I told myself; our house, our world.

And still the bird sang in the locust tree.

“ Listen to it,” Beth sat up, pulling the sheet to her chin and leaning forward on her knees.

“I could have killed it. What’s today?”

“Saturday.”

“Thought so.” I snuggled some more, pleased that I had been right. “Then we can stay right here-”

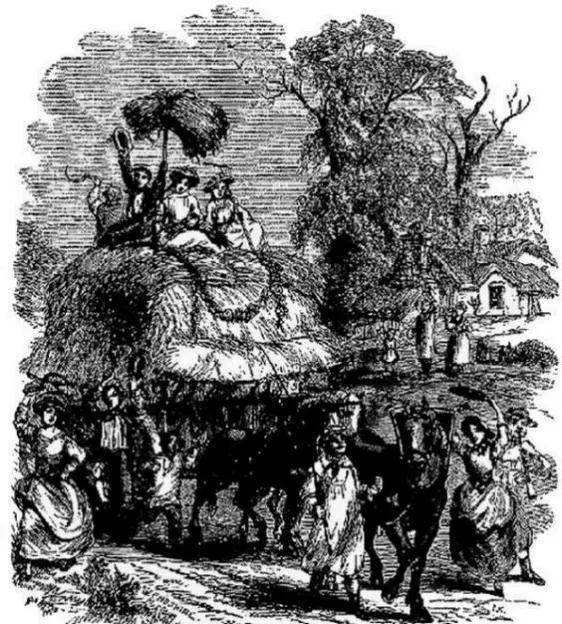

“Don’t you know what day it is?” She laughed a gay, light laugh that was all her own. “It’s fair day, remember? The Agnes Fair?”

Of course-I had forgotten. The last Saturday in August was the day of the village fair, an annual tradition. I had been hearing of little else for weeks.

Читать дальше