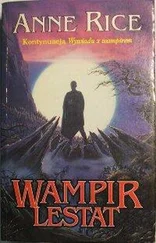

Anne Rice - The Vampire Lestat

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anne Rice - The Vampire Lestat» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Vampire Lestat

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Vampire Lestat: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Vampire Lestat»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Vampire Lestat — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Vampire Lestat», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I know how it is, " she said to me. "You hate them. Because of what you've endured and what they don't know. They haven't the imagination to know what happened to you out there on the mountain. " I felt a cold delight in these words. I gave her the silent acknowledgment that she understood it perfectly.

"It was the same the first time I bore a child, " she said. "I was in agony for twelve hours, and I felt trapped in the pain, knowing the only release was the birth or my own death. When it was over, I had your brother Augustin in my arms, but I didn't want anyone else near me. And it wasn't because I blamed them. It was only that I'd suffered like that, hour after hour, that I'd gone into the circle of hell and come back out. They hadn't been in the circle of hell. And I felt quiet all over. In this common occurrence, this vulgar act of giving birth, I understood the meaning of utter loneliness. "

"Yes, that's it, " I answered. I was a little shaken. She didn't respond. I would have been surprised if she had. Having said what she'd come to say, she wasn't going to converse, actually. But she did lay her hand on my forehead-very unusual for her to do that-and when she observed that I was wearing the same bloody hunting clothes after all this time, I noticed it too, and realized the sickness of it. She was silent for a while. And as I sat there, looking past her at the fire, I wanted to tell her a lot of things, how much I loved her particularly. But I was cautious. She had a way of cutting me off when I spoke to her, and mingled with my love was a powerful resentment of her. All my life I'd watched her read her Italian books and scribble letters to people in Naples, where she had grown up, yet she had no patience even to teach me or my brothers the alphabet. And nothing had changed after I came back from the monastery. I was twenty and I couldn't read or write more than a few prayers and my name. I hated the sight of her books; I hated her absorption in them. And in some vague way, I hated the fact that only extreme pain in me could ever wring from her the slightest warmth or interest. Yet she'd been my savior. And there was no one but her. And I was as tired of being alone, perhaps, as a young person can be. She was here now, out of the confines of her library, and she was attentive to me. Finally I was convinced that she wouldn't get up and go away, and I found myself speaking to her.

"Mother, " I said in a low voice, "there is more to it. Before it happened, there were times when I felt terrible things. " There was no change in her expression. "I mean I dream sometimes that I might kill all of them, " I said. "I kill my brothers and my father in the dream. I go from room to room slaughtering them as I did the wolves. I feel in myself the desire to murder... "

"So do I, my son, " she said. "So do I " And her face was lighted with the strangest smile as she looked at me. I bent forward and looked at her more closely. I lowered my voice.

"I see myself screaming when it happens, " I went on. "I see my face twisted into grimaces and I hear bellowing coming out of me. My mouth is a perfect O, and shrieks, cries, come out of me. " She nodded with that same understanding look, as if alight were flaring behind her eyes.

"And on the mountain, Mother, when I was fighting the wolves . . . it was a little like that. "

"Only a little? " she asked. I nodded.

"I felt like someone different from myself when I killed the wolves. And now I don't know who is here with you-your son Lestat, or that other man, the killer. " She was quiet for a long time.

"No, " she said finally. "It was you who killed the wolves. You're the hunter, the warrior. You're stronger than anyone else here, that's your tragedy. " I shook my head. That was true, but it didn't matter. It couldn't account for unhappiness such as this. But what was the use of saying it? She looked away for a moment, then back to me.

"But you're many things, " she said. "Not only one thing. You're the killer and the man. And don't give in to the killer in you just because you hate them. You don't have to take upon yourself the burden of murder or madness to be free of this place. Surely there must be other ways. " Those last two sentences struck me hard. She had gone to the core. And the implications dazzled me. Always I'd felt that I couldn't be a good human being and fight them. To be good meant to be defeated by them. Unless of course I found a more interesting idea of goodness. We sat still for a few moments. And there seemed an uncommon intimacy even for us. She was looking at the fire, scratching at her thick hair which was wound into a circle on the back of her head.

"You know what I imagine, " she said, looking towards me again.

"Not so much the murdering of them as an abandon which disregards them completely. I imagine drinking wine until I'm so drunk I strip off my clothes and bathe in the mountain streams naked. " I almost laughed. But it was a sublime amusement. I looked up at her, uncertain for a moment that I was hearing her correctly. But she had said these words and she wasn't finished.

"And then I imagine going into the village, " she said, "and up into the inn and taking into my bed any men that come there-crude men, big men, old men, boys. Just lying there and taking them one after another, and feeling some magnificent triumph in it, some absolute release without a thought of what happens to your father or your brothers, whether they are alive or dead. In that moment I am purely myself. I belong to no one. " I was too shocked and amazed to say anything. But again this was terribly, terribly amusing. When I thought of my father and brothers and the pompous shopkeepers of the village and how they would respond to such a thing, I found it damn near hilarious. If I didn't laugh aloud it was probably because the image of my mother naked made me think I shouldn't. But I couldn't keep altogether quiet. I laughed a little, and she nodded, half smiling. She raised her eyebrows, as if to say, 'We understand each other'. Finally I roared laughing. I pounded my knee with my fist and hit my head on the wood of the bed behind me. And she almost laughed herself. Maybe in her own quiet way she was laughing. Curious moment. Some almost brutal sense of her as a human being quite removed from all that surrounded her. We did understand each other, and all my resentment of her didn't matter too much. She pulled the pin out of her hair and let it tumble down to her shoulders. We sat quiet for perhaps an hour after that. No more laughter or talk, just the fire blazing, and her near to me. She had turned so she could see the fire. Her profile, the delicacy of her nose and lips, were beautiful to look at. Then she looked back at me and in the same steady voice without undue emotion she said:

"I'll never leave here. I am dying now. " I was stunned. The little shock before was nothing to this.

"I'll live through this spring, " she continued, "and possibly the summer as well. But I won't survive another winter. I know. The pain in my lungs is too bad. " I made some little anguished sound. I think I leaned forward and said, "Mother! "

"Don't say any more, " she answered. I think she hated to be called mother, but I hadn't been able to help it.

"I just wanted to speak it to another soul, " she said. "To hear it out loud. I'm perfectly horrified by it. I'm afraid of it. " I wanted to take her hands, but I knew she'd never allow it. She disliked to be touched. She never put her arms around anyone. And so it was in our glances that we held each other. My eyes filled with tears looking at her. She patted my hand.

"Don't think on it much, " she said. "I don't. Just only now and then. But you must be ready to live on without me when the time comes. That may be harder for you than you realize. " I tried to say something; I couldn't make the words come. She left me just as she'd come in, silently. And though she'd never said anything about my clothes or my beard or how dreadful I looked, she sent the servants in with clean clothes for me, and the razor and warm water, and silently I let myself be taken care of by them.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Vampire Lestat»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Vampire Lestat» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Vampire Lestat» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.