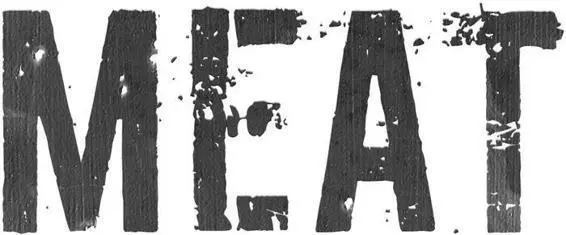

Joseph D’Lacey

This book is for Foxy, my mainstay and the love of my life.

Behold I have given you every herb bearing seed which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.

Genesis 1:29

Briefly, to my publisher and editor, Simon Petherick, for edging out along an untested branch and to my family for encouraging it to grow. To my in-laws for keeping faith and to my friends for being true. To all – whether Beautiful or Bloody – for their enthusiasm.

My thanks also to Colin Smythe, Lisanne Radice, Stephen Calcutt, Kate Pool, Kenilworth Writers and Doomey, Deplancher & Theo at www.tqrstories.comfor their support.

And especially to you, for opening this book.

Under skies of tarnished silver, towards the granite clouds, Richard Shanti runs home.

Step after crushing step, his breath falling in and out of strange rhythms with the pounding of his feet. Mucus building at the back of his throat – the only moisture left in his body. His legs alternately telling him that they’re burning beyond endurance, that they’re too weak to go on. He wants to listen.

Instead, he spits out his precious phlegm.

He’s out of sweat. The last of it has dried at his temples and his bearded face is aflame. His eyes sting with salt but there are no tears left to clear them. He’s desiccating on the run.

He smiles.

His thighs and calves are blowtorched. Blazing, blazing, blazing with every step. His muscles are lava and jelly. There’s no strength left in them; not an ounce of goodness or grace.

Not yet.

His shins bend with each burdened contact. He can feel them giving under the load. He imagines hairline cracks appearing in the immaculate bones and a snap – the sound of a wooden ruler breaking under water. It extends his pain. The sound of that damp splintering lingers in his aura; echoes eternal in his ears.

How much will it take to clear the backlog? I’ll do anything . I want my purity back .

He runs.

There’s a limitless tempo to it. Pain is the punctuation. The percussion of his soles on the stony road is a beat of torment.

Thack-thack-thack-thack-thack-thack-thack.

He runs.

It is his only salvation. He runs. He pays.

This life is not long enough to clear him of the ill he has begotten. By his own hand he is condemned. Every part of him must atone. The agony in the soles of his feet lances up into the marrow of his ankles. He visualises stress fractures creeping through his tarsals.

He runs; willing the pain into his body. The pack hammers his back as though it is alive. Every step forces it up and then slams it down against his spine. There is no harmonious pace. The straps chafe his shoulders and the weight threatens to pull him over backwards. Every movement pounds him, grinds him down.

His lungs are dry with the frenetic passing of air. Smoke from the meat trucks clings in his throat until it is distilled to a tainted scum that sickens him.

He runs. He pays. He prays.

The pain is with him all the time now. The damage in his joints and bones scrapes along his nerves each moment of the day. His existence is a whiteness of suffering.

Perhaps I am getting clear .

‘Hey, Ice Pick!’ Bob Torrance shouted from the elevated observation box at the top of the steel stairs, ‘What’s the chain speed today?’

Shanti checked the stun-counter beside the access panel against the main clock.

‘Running at a hundred and thirty an hour, sir.’

Torrance smiled in admiration and delight. High chain speeds meant bonuses for everyone. They made him look good with the men and with Rory Magnus.

‘You wipe out cattle like a disease, Rick. Keep it up.’

Shanti was the calmest employee in Magnus Meat Processing and Bob Torrance, the chain manager, loved him. He’d never seen another man like him. They called him the Ice Pick or Ice Pick Rick because of the total cool with which he manned the stun gun. Psychologically, it was one of the toughest jobs on the chain; the most damaging to the mind. For this reason the position was rotated between four trained stunners on the work force, each taking a week of stunning followed by three weeks on other areas of the chain or elsewhere in the factory. No one could kill hour after hour, day after day, month after month without something coming permanently adrift in their head. A break was mandatory for the sake of sanity and, more crucially, to maintain high productivity.

But if anyone could lay a captive bolt gun to the brow of a living creature from this day to retirement without a single day off, it was the Ice Pick, Richard Shanti. If anyone could look into the eyes of the soon-to-be-bled-gutted-quartered-and-packed for the rest of his life without a hint of damage to the psyche, it was he.

And look into their eyes he did. Everyone had seen him do it.

For most stunners, it was the eyes that were the problem. Torrance understood why – he’d been a stunner himself in his youth. He knew it was the toughest job in the slaughterhouse. How could you watch the light go out of thousands of pairs of eyes and not be affected by it? How could you not wonder where that light went? How could you not wonder if there was something wrong in what you were doing?

These questions layered up in a person’s head. Each passing pair of eyes had their own character and texture. Each pair of eyes was unique.

So what, if Shanti didn’t mix with the other workers? So what, if he ran himself to the edge of collapse every night and morning? As long as he turned up on time and did the kind of quality work he always had, Torrance had no complaints.

Every stunner needed a way of counteracting the job. If running helped Shanti cope, that suited Bob Torrance. He smiled to himself as he imagined Shanti sweating his way home of an evening.

It couldn’t have suited him better.

Management had learned over the decades that stunners needed time out from the job they were trained for otherwise they didn’t last. Torrance had seen it a few times in his long career at MMP. He remembered one young employee in particular:

Stunner Wheelie Patterson had been a jovial, fresh-faced boy when he started out. Pulled the front wheel of his push-bike high in the air on his way out of the yards every evening, thinking it was impressive and making everyone laugh. He was keen, sincere and committed to his work. He told the chain manager at the time – a fool with no instincts called Eddie Valentine – that he could handle two weeks at a time on the stun. It was a mistake for Valentine to let him do it, but back then there had only been religious guidelines for workers to follow – nothing secular or practical.

The kid had worked at the head of the chain like he was one of the machines. The conveyor would roll, the aluminium panel would open bringing a restrained head into view. Wheelie would voice the blessing, ‘God is supreme. The flesh is sacred,’ then whack the head with a sharp hiss and metallic clunk from the captive bolt gun. The panel would slide closed. He’d hit the proceed button and the conveyor would roll again.

The panel would open.

Head.

Eyes.

‘God is supreme. The flesh is sacred.’

Hiss-Clunk.

The panel would close.

The stun counter spun higher.

Wheelie worked that way – two weeks on, two weeks off – for six months. Each night he rode home on the bike everyone had come to know as the unicycle owing to his customary flourish in the forecourt. The other two weeks saw him ‘on the bleed’ or herding the cattle into the crowd pens and single file chute with an electric prod.

Читать дальше