He stepped back into his bedroom and looked at the head, perched where he had left it. The thing stared at him with its coal-black, swollen eyes. It seemed bigger than before, like an oversized, blackened grapefruit. You know, he thought suddenly, you know what happened, you black swine of a devil! But no, this was madness. How could he believe that the thing had some sort of connection with what had happened? It must be something else. But what? he wondered. What but something equally bizarre, equally preposterous could account for it?

What?

What?

Outside he heard the two-tone siren of a police car as it sped down the road. After it had gone there was another. Lamson strode to the window and looked down as an ambulance hurtled by, its blue light blinking furiously.

He leant against the windowsill, feeling suddenly weak. Resignedly, he knew that it happened, it really did happen. By now they must have found her blood-soaked body, or what was left of it. He gazed down at the stains still sticking to his fingers, and wondered what he could do. Like the Brand of Cain, threads of blood clung to the hardened scales about his knuckles. If only he had thrown that stone away when he’d intended to originally. If he had, he was sure that none of this would have ever happened. He grabbed hold of the stone, clenching it tightly as if to crush it into dust. Something black seemed to move on the edge of his sight. He turned round in surprise, but there was nothing there now.

He placed the head back on the dresser and took a deep breath to compose himself. He wondered if he had left it too late to get rid of the head. Or was there time yet? After all, there was no saying what the thing might make him do next. Reluctantly, he looked again at the head. How he wished he could convince himself that it was nothing more than just an inanimate lump of stone. Once more he picked it up, his fingers experiencing the same kind of revulsion he would have felt on touching a diseased piece of flesh.

‘Damn you,’ he whispered tensely, suddenly flexing his arm. There was a movement by his side, furtive and vague. He whipped round. ‘Where are you hiding?’ he asked shakily, searching round the empty room. There seemed to be a sound somewhere, like the clattering of hoofs. Or was there? It echoed metallically, almost unreal. ‘Come on, now, where are you hiding?’ Something touched his arm. He cried out inarticulately in revulsion. ‘Go away!’ he choked, retreating to the window. He turned round to look outside, raising his hand and glancing at the head clasped tightly in his fingers.

Steady, now, steady, he told himself. Don’t lose your grip altogether.

He coughed harshly, feeling the phlegm in his throat. It involuntarily dribbled from his lips and spilt on the floor. Looking down, he saw a string of blood in it. He closed his eyes tightly. He knew what it meant, though he wished fervently that he could believe that it didn’t. He wished that he could have known earlier what he knew now and done then what he was about to do, when it wasn’t already too late.

‘God help me!’ he cried as he tugged his arm free of the fingers that plucked at him, and flung the stone through the window. There was a crash as the glass was shattered, and he fell to the floor.

Something rose up above him, seeming monstrously large in the gloom of his faltering sight.

‘Are you going up to see Mr. Lamson?’ the elderly woman asked, detaining Sutcliffe with a nervously insistent hand.

‘I am,’ he replied. ‘Why? Is there something wrong?’ He did not try to hide his impatience. He was nearly half an hour late already.

‘I don’ t know,’ she said, glancing up the stairs apprehensively. ‘It was late this afternoon when it happened. I was cleaning the dishes after having my tea when I heard something crash outside. When I looked I found there was broken glass all over the flagstones. It had come from up there,’ she pointed up the stairs, ‘from the window of Mr. Lamson’s flat; his window had been broken.’

His impatience mellowing into concern, Sutcliffe asked if anyone had been up to see if he was all right.

‘Do you know if he’s been hurt? He hasn’t been too well recently and he might be sick.’

‘I went up to his rooms, naturally,’ the woman said. ‘But he wouldn’t answer his door. On no account would he, even when I called out to him, though he was in there right enough. I could hear him, you see, bumping around inside. Tearing something up, I think he was. Like books, I s’ppose. But he wouldn’t open the door to me. He wouldn’t even talk. Not one word. There was nothing more I could do, was there?’ she apologized. ‘I didn’t know he was ill.’

‘That’s all right,’ Sutcliffe said, thanking her for warning him. ‘I’ll be able to see how he is when I call up. I’m sure he’ll answer his door to me when I call to him. By the way,’ he went on to ask, turning round suddenly on the first step up the stairs, ‘do you know what it was that broke the window?’

‘Indeed I do,’ the woman said. She felt in the pocket of her apron. ‘I found this on the pavement when I went out to clear up the glass. It’s been cracked, as you can see.’ She handed him the stone. ‘Ugly looking thing, isn’t it?’

‘It certainly is.’ Sutcliffe felt at the worn features on its face. It was pleasantly soap-like and warm. He wondered why Lamson should have thrown something like this through his window. ‘Do you mind if 1 hold onto it for a while?’ he asked.

‘You can keep it for good for all I care. I don’t want it. I’m certain of that, Lord knows! It’d give me the jitters to keep an evil-looking thing like that in my rooms.’

Thanking her again, Sutcliffe bounded up the stairs, three at a time. He wondered worriedly if Lamson had thrown it through the window as a cry for help. Just let me be in time if it was, he thought, knocking on his door. ‘Henry! Are you in there? It’s me, Allan. Come on, open up!’

There was no sound.

Again he knocked, louder this time.

‘Henry! Open up, will you?’ Apprehensively, he waited an instant more, then he took hold of the door handle, turning it. ‘Henry, I’m coming in. Keep well away from the door.’ Heavily, he lunged against the door with his shoulder. The thin wood started to give way almost at once. Again he lunged against it, then again, then the door shot open, propelling Sutcliffe in with it.

‘Where are you, Henr—’ he began to call out as he steadied himself, before he saw what lay curled against the windowsill. Shuddering with nausea, Sutcliffe clasped a hand to his mouth and turned away, feeling suddenly sick. Naked and almost flayed to the bone, with tears along his doubled back, Lamson was crouched like a grotesque foetus amongst the blood-soaked tatters of his clothes. His head was twisted round, and it was obvious that his neck had been broken. But it was none of this, neither the mutilations nor the gore nor the look of horror and pain on Lamson’s rigidly contorted face, that were to haunt him in the months to come, but an expression that lay raddled across his friend’s dead face which he knew should have never been there — a look of joyful ecstasy. And there was a hunger there, too, but a hunger that went further than that of mere hunger for food.

* * *

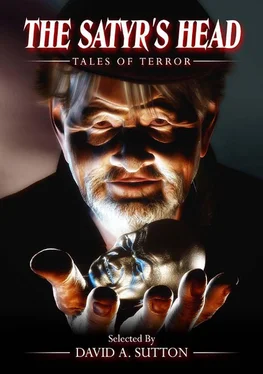

The Satyr’s Head: Tales of Terror

First published as The Satyr’s Head & Other Tales of Terror

by Corgi Books 1975

This edition © 2012 by David A. Sutton

Cover artwork & design © 2012 by Steve Upham

The Nightingale Floors © 1975 by James Wade

The Previous Tenant © 1975 by Ramsey Campbell

The Night Fisherman © 1975 by Martin I. Ricketts

Sugar and Spice and All Things Nice © 1975 by David A. Sutton

Читать дальше