Intent on adding whatever gloss of credibility to his tale that he could, the old tramp continued, saying:

‘It were in a brook. I found it by chance as I were gettin’ m’self some water for a brew. It’d make a nice paperweight, I thought. I thought so as soon as I saw it. It’d make a nice paperweight, I thought.’ He laughed self-indulgently, wiping his mouth with the sleeve of his coat. ‘But I’ve no paper to put it on.’

Lamson looked down at the carving and smiled.

When the bus drew up at the terminus, Lamson was surprised, though not dismayed, when the tramp hurriedly climbed off and merged with the passing crowds outside. His bowlegged gait and crookedly unkempt figure were too suggestive of sickness and deformity for Lamson’s tastes, and he felt more eager than ever for a salutary pint of beer in a pub before going on home to his flat.

Pressing his way through the queues outside the Cinerama on Market Street, he made for the White Bull, whose opaque doors swung open steamily before him with an out blowing bubble of warm, beery air.

One drink later, and another in hand, he stepped across to a vacant table up in a corner of the lounge, placing his glass beside a screwed-up bag of crisps.

A group of men were arguing amongst themselves nearby, one telling another, as of someone giving advice:

‘A standing prick has no conscience.’

There was a nodding of heads and another affirmed: ‘That’s true enough.’

Disregarding them as they sorted out what they were having for their next round of drinks, Lamson reached in his pocket and brought out the head. A voice on the television fixed above the bar said:

‘You can be a Scottish nationalist or a Welsh nationalist and no one says anything about it, but as soon as you say you’ re a British nationalist, everyone starts calling out "Fascist!"’

Two of the men nodded to each other in agreement.

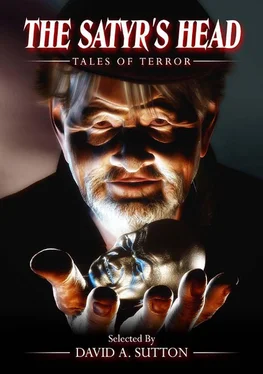

Holding the head in the palm of his hand, Lamson realized for the first time just how heavy it was. If not for the broken neck, which showed clearly enough that it was made out of stone, he would have thought it to have been molded from lead. As he peered at it, he noticed that there were two small ridges on its brows which looked as though they had once been horns

As he studied them, he felt that if they had remained in their entirety, the head would have looked almost satiric, despite the bloated lips. In fact, the slightly raised eyebrows and long, straight nose — or what remained of them — were still reminiscent of Pan.

He heard a glass being placed on the table beside him. When he looked up he saw that it was Allan Sutcliffe.

‘I didn’t notice you in here before. Have you only just got in?’ Lamson asked.

Sutcliffe wiped his rain-spotted glasses on a handkerchief as he sat down, nodding his head. He replaced his glasses, then thirstily drank down a third of his pint before unbuttoning his raincoat and loosening the scarf about his neck. His face was flushed as if he had been running.

‘I didn’t think I’d be able to get here in time for a drink. I have to be off again soon to get to the Film Society. What have you got there, Henry? You been digging out your garden or something?’

Almost instinctively, Lamson cupped his hands about the head.

‘It’d be strange sort of garden in a second floor flat, wouldn’t it?’ he replied acidly.

He drew his hands in towards his body, covering what little still showed of the head with the ends of his scarf. Somehow he felt ashamed of the thing, almost as if it was obscene and repulsive and peculiarly shameful.

‘Where did you say you were off to?’ he asked, intending to change the subject. ‘The Film Society? What are they presenting tonight?’

‘ Nosferatu . The original. Why? D’you fancy coming along to it as well? It’s something of a classic, I believe. Should be good.’

Lamson shook his head.

‘Sorry, but I don’t feel up to it tonight. I only stopped in for a pint or two before going on home and getting an early night. I’ve had a long day already, what with helping my brother, Peter, redecorating the inside of his farmhouse. I’m about done in.’

Glancing significantly at the clock above the bar, Sutcliffe drained his glass, saying, as he placed it back on the table afterwards: ‘I’ll have to be off now. It starts in another ten minutes.’

‘I’11 see you tomorrow as we planned,’ Lamson said. ‘At twelve, if that’s still okay?’

Sutcliffe nodded as he stood up to go.

‘We’ll meet at the Wimpy, then I can get a bite to eat before we set off for the match.’

‘Okay.’

As Sutcliffe left, Lamson opened his sweat-softened hands and looked at the head concealed in the cramped shadows in between. Now that his friend had gone, he felt puzzled at his reaction with the thing. What was it about the thing that should affect him like this? he wondered to himself. Placing it back in his pocket, he decided that he had had enough of the pub and strode outside, buttoning his coat against the rain.

Sunlight poured with a cold liquidity through his bedroom window when Lamson awoke. It shone across the cellophane that protected the spines of the hardbound books on the shelves facing his bed, obscuring their titles. It seemed glossy and bright and clean, with the freshness of newly fallen snow.

Yawning contentedly, he stretched, then drew his dressing gown onto his shoulders as he gazed out of the window. Visible beyond the roof opposite was a bright and cloudless sky. He felt the last dull dregs of sleep sloughing from him as he rubbed away the fine granules that had collected in his eyes. Somewhere he could hear a radio playing a light pop tune, though it was almost too faint to make out.

Halfway through washing he remembered the dreams. They had completely passed from his mind on wakening, and it was with an unpleasant shudder that they returned to him now.

The veneer of his cheerfulness was dulled by the recollection, and he paused in his ablutions to look back at his bed. They were dreams he was not normally troubled with, and he was loath to think of them now.

‘To Hell with them!’ he muttered self-consciously as he returned to scrubbing the threads of dirt from underneath his nails.

The measured chimes of the clock on the neo-Gothic tower, facing him across the neat churchyard of St. James, were tolling midday when Lamson walked past the Municipal Library. Sutcliffe, who worked at a nearby firm of accountants as an articled clerk, would be arriving at the Wimpy further along the street any time now. Going inside, Lamson ordered himself a coffee and took a seat by the window. He absent-mindedly scratched his hand, wondering nonchalantly, when he noticed what he was doing, if he had accidentally brushed it against some of the nettles that grew up against the churchyard wall. A few minutes later Sutcliffe arrived, and the irritation passed from his mind, forgotten.

‘You’re looking a bit bleary eyed today, Henry,’ Sutcliffe remarked cheerfully. ‘An early night, indeed! Too much bed and not enough sleep, that’s your trouble.’

‘I wish it was,’ Lamson replied. ‘I slept well enough last night. Too well, perhaps.’

‘Come again?’

‘Some dreams—’ Lamson started to explain, before he was interrupted by Sutcliffe as the waitress arrived.

‘Wimpy and chips and coffee, please.’

When she’d gone, Sutcliffe said: ‘I’m sorry. What was that you were saying?’

But the inclination to tell him had gone. Instead, Lamson talked about the Rovers’ chances this afternoon in their match against Rochdale. As they spoke, though, his mind was not wholly on what they were talking about. He was troubled, though he did not know properly why, by the dreams he had been about to tell Sutcliffe about, but which, on reconsideration, he had decided to keep to himself.

Читать дальше