All life on earth consists of one or more cells containing DNA (or, in some cases, RNA). The nuclei of these cells contain molecular compounds known as nucleic acids. There are two types of nucleic acids: DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid). These play different roles. DNA is the compound in which genetic information is stored in the chromosomes: it takes the form of two long threads twisted about one another in a spiral, a shape known as the double helix. The sum total of a life form’s genetic information is inscribed within that double structure. This genetic information is like a set of blueprints for the construction of specialized proteins; each gene is a blueprint. In other words, genes and DNA are not the same thing. A gene is a unit of information.

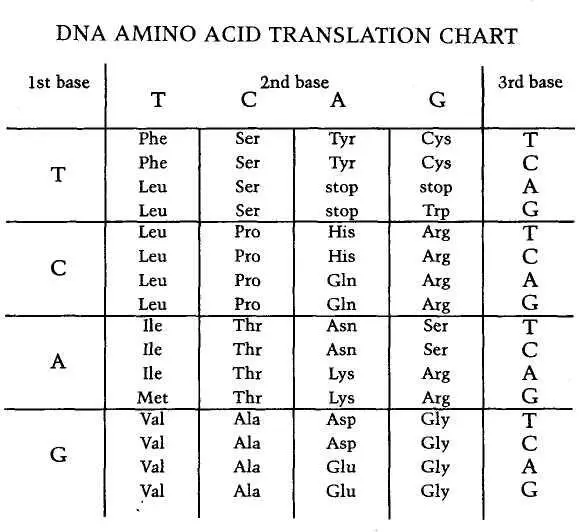

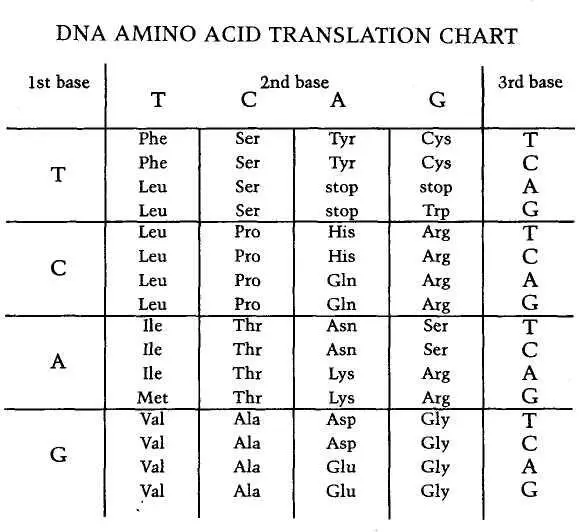

So what exactly is written on these blueprints? The letters that make up the inscriptions are four chemical compounds known as bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T) or in the case of RNA, uracil (U). These four bases work in sets of three called codons, which are translated into amino acids. For example: the codon AAC makes asparagine, the codon GCA makes alanine, etc.

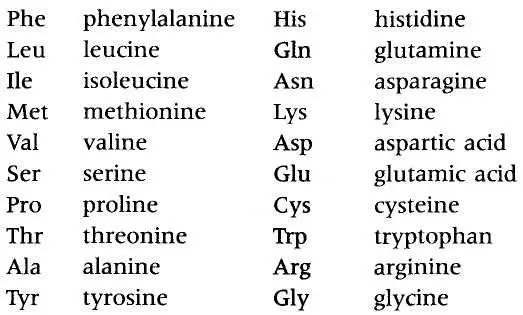

Proteins are conglomerations of hundreds of these amino acid molecules, of which there are twenty types. This means that the blueprint for one protein must contain an array of bases equal in number to the number of amino acid molecules times three.

The blueprint called the gene can be thought of, then, as basically a long line of letters, looking something like this: TCTCTATACCAGTTG-GAAAATTAT… Translated, this signifies a series of amino acids that runs: TCT (serine, or Ser), CTA (leusine, or Leu), TAC (tyrosine, Tyr), CAG (glutamine, Gln), TTG (leusine, Leu), GAA (glutamic acid, Glu), AAT (asparagine, Asn), TAT (tyrosine, Tyr), etc. etc.

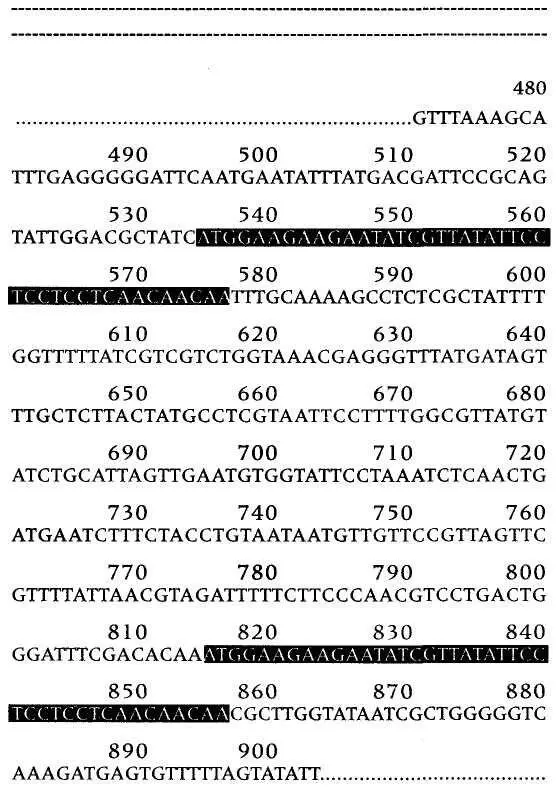

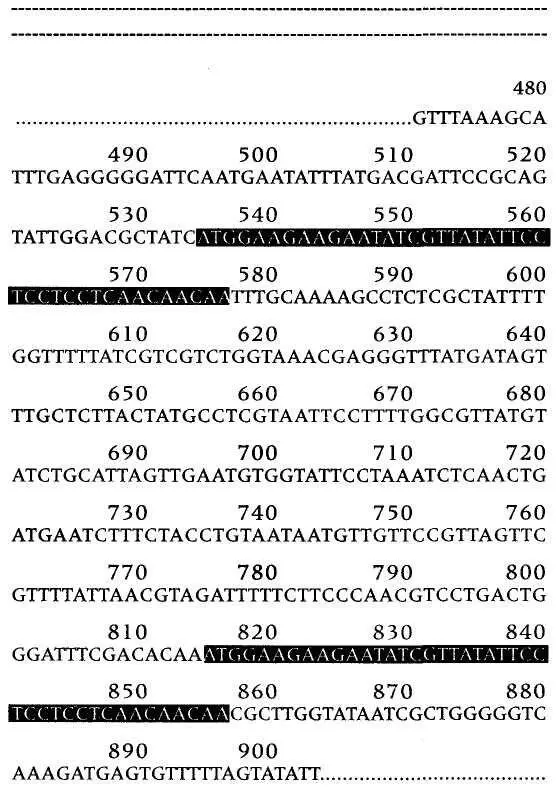

Ando glanced again at the base codes covering the printout, the four letters A, T, G, and C lined up seemingly at random across the page. Segments of three rows had been highlighted so as to stand out from the rest.

“What’s this?”

Miyashita winked at Nemoto, as if to say, you tell him.

“This is an analysis of a segment of DNA taken from the virus found in Ryuji Takayama’s blood.”

“Okay… so what’s this?”

“We found a rather strange sequence of bases, something we’ve only seen in Takayama’s virus.”

“And that’s what’s highlighted here?”

“That is correct.”

Ando took a closer look at the first highlighted series of letters.

ATGGAAGAAGAATATCGTTATATTCCTC CTCCTCAACAACAA

He looked at the next highlighted portion, and compared it with the first. He realized it was exactly the same sequence. In a group of not even a thousand bases, the exact same sequence occurred twice.

Above: between #535 and #576, and again between #815 and #856, one can observe the repetition of the 42 bases ATGGAAGAA-GAATATCGTTATATTCCTCCTCCTCAACAACAA.

Base triplets (codons) are translated into amino acids according to the principles outlined in the chart above. For example, TCT is serine (Ser), AAT is asparagine (Asn), GAA is glutamic acid (Glu). “Stop” signifies the end of a gene; the beginning code is ATG.

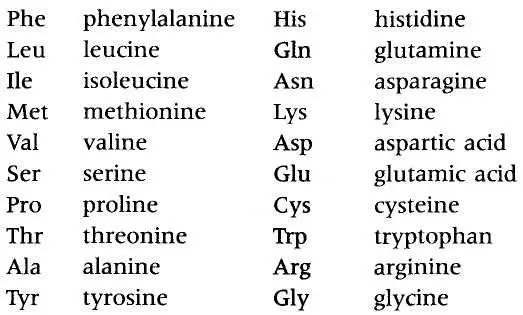

Below are the abbreviated and full names of the twenty amino acids:

Ando shifted his gaze from the printout to Nemoto’s face.

“No matter where we slice it, we always find this identical sequence.”

“How many of these are there?”

“Bases, you mean?”

“Yeah.”

“Forty-two.”

“Forty-two. So, fourteen codons, right? That’s not very many.”

“We think it means something,” Nemoto said, shaking his head. “But, Dr Ando, the strange thing is…”

Miyashita interrupted. “This meaningless repetition was only found in the virus collected from Ryuji Takayama’s blood, and not from the other two victims.” He threw up his hands in a gesture of perplexity.

In other words.… Ando tried to find a suitable analogy. Suppose three people, one being Ryuji, had copies of Shakespeare’s King Lear. Then suppose that Ryuji’s copy, and only his copy, had meaningless strings of letters sandwiched in between the lines. There were forty-two bases, and they worked in sets of three, each set corresponding to one amino acid. If you assigned each of these sets a letter, you’d have a series of fourteen letters. And these fourteen repeating letters were found on every page of the play, inserted at random. If you knew from the beginning that the play was King Lear, of course, it would be possible to go back and find the meaningless parts that had been interpolated and highlight them.

“So what do you think?” Miyashita looked to be sincerely interested in Ando’s opinion. A true scientist, he was always most excited when confronted with the inexplicable.

“What do I think? I’d have to know more before I could say anything.”

The three of them fell silent, glancing at one another’s faces. Ando felt awkward, still holding the printout.

Something was tugging at his consciousness. In order to figure out what it was, he needed time to sit down and study the meaningless string of bases. He had an unmistakable premonition that there was something here. The question was, what? And if this meaningless base sequence had indeed been interpolated, when had it happened? Was the virus that had invaded Ryuji’s body just different? Or had it mutated in Ryuji’s body, with the fourteen-codon string appearing here and there as a result of that mutation? Was that even possible? And if it was, what did it mean?

An oppressive silence fell over the three men. No amount of speculation at this point could tell them how to interpret these findings.

It was Miyashita who broke the silence. “By the way, did you come here for a reason?”

Ando had been so intrigued by the discovery that his original errand had slipped his mind. “Right, I almost forgot.” He opened up his briefcase, took out his planner, and showed Miyashita and Nemoto a slip of paper.

“I was wondering if anyone here had a word processor of this model.”

Miyashita and Nemoto looked at the model name written on the paper. It was a fairly common machine.

“Does it have to be exactly the same model?”

“As long as it’s the same brand, the model probably isn’t important. Basically, it’s a question of compatibility for a floppy disk.”

“Compatibility?”

“Yes.” Ando took a floppy disk from his briefcase.

“I need to make a hard copy and a soft copy of the files on this disk.”

“It’s not saved in MS-DOS, I take it?”

“I don’t think so.”

Nemoto clapped his hands, as if he’d just remembered something. “Hey, one of the staff members in my department-Ueda, I think-has this very model.”

“Do you suppose he’d let me borrow it?” Ando hesitated. He’d never met this Ueda.

“I don’t imagine there’d be a problem. He’s fresh out of school.” Nemoto spoke with the confidence of a senior staff member who knew that a new resident would do anything he asked.

“Thanks.”

“No problem at all. Why don’t we go over right now? I think he’s there.”

This was music to Ando’s ears. He couldn’t wait to print out whatever was on this disk.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу