“But… but…” Dimly I realised I was crying too. This was my wife. My wife , for Christ’s sake.

Diane forced a smile. “Just stay put. Or try… make a getaway.”

“I’m not leaving you.”

“Yes, you are. It’ll go after you. Might be able… drag myself there.” She nodded at the boulder. “You could go get help. Help me. Might stand a chance.”

I looked at the blood still bubbling up from the stones. She must have seen the expression on my face. “Like that, is it?”

I looked away. “I can try.” My view of the gully was still constricted by my position. I could see the floor of it sloping up, but not how far it ultimately went. If nothing else, I could draw it away from her, give her a chance to get to the boulder.

And what then? If I couldn’t find a way out of the gully? If there wasn’t even a boulder to climb to safety on, I’d be dead and the best Diane could hope for was to bleed to death.

But I owed her a chance of survival, at least.

I put the backpack down, looked into her eyes. “Soon as it moves off, start crawling. Shout me when you’re here. I’ll keep making a racket, try and keep it occupied.”

“Be careful.”

“You too.” I smiled at her and refused to look at her feet. We met at University, did I tell you? Did I mention that? A drunken discussion about politics in the Student Union bar. More of an argument really. We’d been on different sides but ended up falling for each other. That pretty much summed up our marriage, I supposed. “Love you,” I managed to say at last.

She gave a tight, buckled smile. “You too,” she said back.

That was never something either of us had said easily. Should’ve known it’d take something like this. “Okay, then,” I muttered. “Bye.”

I took a deep breath, then jumped off the boulder and started to run.

I didn’t look back, even when Diane let out a cry, because I could hear the rattle and rush of slate behind me as I pelted into the gully and knew the thing had let her go — let her go so that it could come after me.

The ground’s upwards slope petered out quite quickly and the walls all around were a good ten feet high, sheer and devoid of handholds, except for at the very back of it. There was an old stream channel — only the thinnest trickle of water made it out now, but I’m guessing it’d been stronger once, because a mix of earth and pebbles, lightly grown over, formed a slope leading up to the ground above. A couple of gnarled trees sprouted nearby, and I could see their roots breaking free of the earth — thick and twisted, easy to climb with. All I had to do was reach them.

But then I noticed something else; something that made me laugh wildly. Only a few yards from where I was now, the surface of the ground changed from a plain of rubble to bare rock. Here and there earth had accumulated and sprouted grass, but what mattered was that there was no rubble for the creature to move under.

I chanced one look behind me, no more than that. It was hurtling towards me, the huge bow-wave of rock. I ran faster, managed the last few steps, and then dived and rolled across blessed solid ground.

Rubble sprayed at me from the edge of the rubble and again I caught the briefest glimpse of something moving in there. I couldn’t put any kind of name to it if I tried, and I don’t think I want to.

The rubble heaved and settled. The stones clicked. I got up and started backing away. Just in case. Click, click, click. Had anything ever got away from it before? I couldn’t imagine anything human doing so, or men would’ve come back here with weapons, to find and kill it. Or perhaps that survivor hadn’t been believed. Click. Click, click. Click, click, click.

Click. A sheep bleated.

Click. A dog barked.

Click. A wolf howled.

Click. A cow lowed.

Click. A bear roared.

Click. “John?”

Click. “Shona? Shona, where are ye?”

Click. “Mummy?”

Click. “Oh, for God’s sake, Marjorie. For God’s sake.”

Click. “ Down yonder green valley where streamlets meander… ”

Click. “Christ.” My voice. “Christ.”

Click. “Steve? Get help. Help me.” Click. “Steve. Help me.”

I turned and began to run, started climbing. I looked back when I heard stones rattling. I looked back and saw something, a wide shape, moving under the stones and heading away, back towards the mouth of the gully.

“Diane?” I shouted. “Diane?”

There was no answer.

I’ve been walking now, according to my wristwatch, for a good half-hour. My teeth are chattering and I’m tired and all I can see around me is the mist.

Still no signal on the mobile. They can trace your position from a mobile call these days. That’d be helpful. I’ve tried to walk in a straight line, so that if I find help I can just point back the way I came, but I doubt I’ve kept to one.

I tell myself that she must have passed out — passed out from the effort and pain of dragging herself onto that boulder. I tell myself that the cold must have slowed her circulation down to the point where she might still be alive.

I do not think of how much blood I saw bubbling out from under the stones.

I do not think of hypothermia. Not for her. I’m still going, so she still must have a chance there too, surely?

I keep walking. I’ll keep walking for as long as I can believe Diane might still be alive. After that, I won’t be able to go on, because it won’t matter anymore.

I’m crawling, now.

We came out here to see if we still worked, the two of us, under all the clutter and the mess. And it looks like we still did.

There’s that cold comfort, at least.

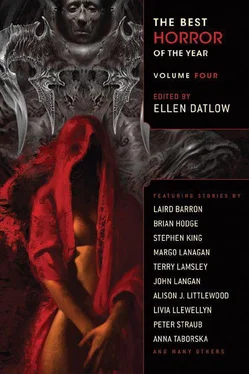

BLACKWOOD’S BABY

Laird Barron

Late afternoon sun baked the clay and plaster buildings of the town. Its dirt streets lay empty, packed as hard as iron. The boarding house sweltered. Luke Honey sat in a chair in the shadows across from the window. Nothing stirred except flies buzzing on the window ledge. The window was a gap bracketed by warped shutters and it opened into a portal view of the blazing white stone wall of the cantina across the alley. Since the fistfight, he wasn’t welcome in the cantina although he’d seen the other three men he’d fought there each afternoon, drunk and laughing. The scabs on his knuckles were nearly healed. Every two days, one of the stock boys brought him a bottle.

Today, Luke Honey was drinking good strong Irish whiskey. His hands were clammy and his shirt stuck to his back and armpits. A cockroach scuttled into the long shadow of the bottle and waited. An overhead fan hung motionless. Clerk Galtero leaned on the counter and read a newspaper gone brittle as ancient papyrus, its fiber sucked dry by the heat; a glass of cloudy water pinned the corner. Clerk Galtero’s bald skull shone in the gloom and his mustache drooped, sweat dripping from the tips and onto the paper. The clerk was from Barcelona and Luke Honey heard the fellow had served in the French Foreign Legion on the Macedonian Front during the Great War, and that he’d been clipped in the arm and that was why it curled tight and useless against his ribs.

A boy entered the house. He was black and covered with the yellow dust that settled upon everything in this place. He wore a uniform of some kind, and a cap with a narrow brim, and no shoes. Luke Honey guessed his age at eleven or twelve, although his face was worn, the flesh creased around his mouth, and his eyes suggested sullen apathy born of wisdom. Here, on the edge of a wasteland, even the children appeared weathered and aged. Perhaps that was how Luke Honey himself appeared now that he’d lived on the plains and in the jungles for seven years. Perhaps the land had chiseled and filed him down too. He didn’t know because he seldom glanced at the mirror anymore. On the other hand, there were some, such as a Boer and another renowned hunter from Canada Luke Honey had accompanied on many safaris, who seemed stronger, more vibrant with each passing season, as if the dust and the heat, the cloying jungle rot and the blood they spilled fed them, bred into them a savage vitality.

Читать дальше