It occurred to me that instead of the usual interview with the devil or a magician, an ingenious use of scientific patter might with advantage be substituted.

—H. G. Wells

The telephone was ringing. I rubbed my eyes and looked out the window (the oak tree was there, all right), looked at the set of hooks (it was in the right place, too). The telephone kept ringing. There was no sound from the old woman’s room on the other side of the wall. I hopped down onto the floor, opened the door (the latch had been on), and went out into the hallway. The telephone was still ringing. It was standing on a little shelf above a large water tub—a very modern piece of equipment in white plastic, like the ones I’d seen in movies and in our director’s office. I picked up the receiver.

“Hello…”

“Who’s that?” asked a piercing woman’s voice.

“Who do you want?”

“Is that Lohuchil?”

“What?”

“I said, is that the Log Hut on Chicken Legs or not? Who is this?”

“Yes,” I said, “this is the hut. Who do you want?”

“Oh, damnation,” said the woman’s voice. “I have a telephonogram for you.”

“All right.”

“Write it down.”

“Just a moment,” I said. “I’ll get a pencil and paper.”

“Oh, damnation,” the woman’s voice repeated.

I came back with a notepad and a pencil. “I’m listening.”

“Telephonogram number 206,” said the woman’s voice. ‘To citizeness Naina Kievna Gorynych…’”

“Not so fast… Kievna Gorynych… OK, what’s next?”

“‘You are hereby… invited to attend… today the twenty-seventh… of July… at midnight… for the annual… republican rally…’ Have you got that?”

“Yes, I have.”

“‘The first meeting… will take place… on Bald Mountain. The dress code is formal… Mechanical transport is available… at your own expense. Signed… Head of Chancellery… C. M. Viy.’”

“Who?”

“Viy! C. M. Viy.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Viy! Chronos Monadovich Viy! You mean you don’t know the head of the chancellery?”

“No, I don’t,” I said. “Spell it out for me.”

“Damnation! All right, I’ll spell it out: Vampire, Incubus, Yeti. Have you got that?”

“I think so,” I said. “I’ve got ‘Viy.’”

“Who?”

“Viy.”

“Have you got adenoids or something? I don’t understand!”

“Vile, Inconceivable, Yucky!”

“Right. Read back the telephonogram.”

I read it back.

“Correct. Transmitted by Onuchkina. Who received it?”

“Privalov.”

“Cheers, Privalov! Been in harness long?”

“Horses wear harness,” I said angrily. “I do a job.”

“You get on with your job then. See you at the rally.”

The phone started beeping. I hung up and went back into the room. It was a cool morning. I rushed through my exercises and got dressed. It seemed to me that something extremely curious was going on. The telephonogram was somehow associated in my mind with the events of the night, although I didn’t have a clue exactly how. But I was beginning to get a few ideas, and my imagination had been stimulated.

There was nothing in what I had witnessed that was entirely unfamiliar to me. I’d read something about similar cases somewhere, and now I remembered that the behavior of people who found themselves in similar circumstances had always seemed to me extremely exasperating and quite absurd. Instead of taking full advantage of the attractive prospects that their good fortune presented to them, they took fright and tried to get back to ordinary, everyday reality. There was even one hero who adjured his readers to keep as far away as possible from the veil that divides our world from the unknown, threatening them with mental and physical impairment. I still did not know how events would unfold, but I was already prepared to take the plunge enthusiastically.

As I wandered around the room in search of a scoop or a mug, I continued with my deliberations. Those timid people, I thought, were like certain experimental scientists, very tenacious and very industrious but absolutely devoid of all imagination and therefore ultracautious. Having produced a nontrivial result, they shy away from it, hastily attempting to explain it away by experimental contamination and effectively rejecting the new because they have grown too accustomed to the old that is so comfortably expounded in authoritative orthodox theory… I was already mulling over several experiments with the whimsical book (it was still lying there on the windowsill, but now it was Aldridge’s The Last Exile ), with the talking mirror, and with sucking my teeth. I had several questions to ask the cat Vasily, and the mermaid who lived in the oak tree was an especially interesting prospect. Although there were moments when I thought I must have dreamed her after all. I’ve got nothing against mermaids, I just can’t imagine how they can clamber around in trees… but then, what about those scales?

I found a dipper on the tub under the telephone, but there was no water in the tub, so I set out for the well. The sun had already risen quite high. There were cars droning along somewhere in the distance, I could hear a militiaman’s whistle, and a helicopter drifted across the sky with a sedate rumbling. Walking up to the well, I was delighted to discover a battered tin bucket on the chain, and I began winding out the rope with the windlass. The bucket sank down into the black depths, clattering against the sides of the well shaft. There was a splash and the chain went taut.

As I turned the windlass I looked at my Moskvich. The car had a tired, dusty look; the windshield was plastered with midges that had been flattened against it. I’ll have to put some water in the radiator, I thought. And all those other jobs…

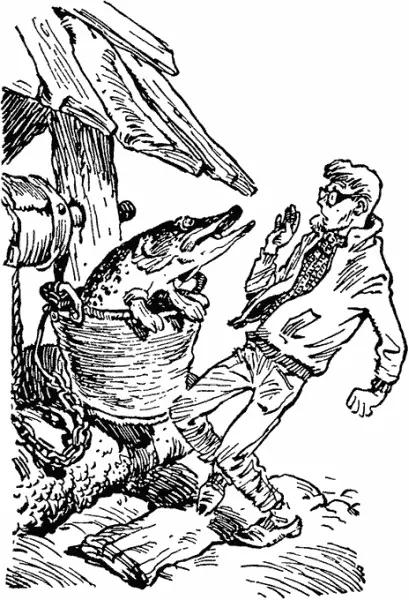

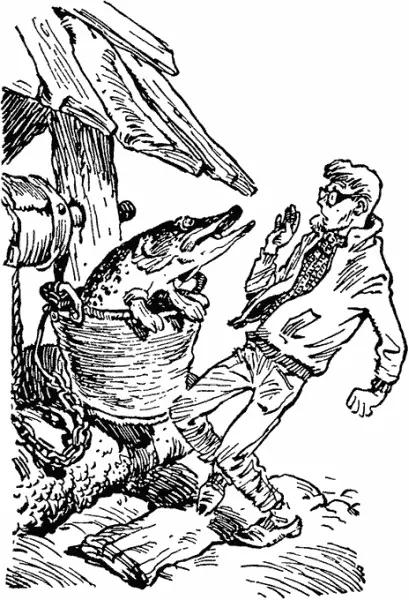

The bucket seemed very heavy. When I stood it on the wall of the wooden well, a huge pike stuck its green, mossy-looking head up out of the water. I jumped back.

“Are you going to drag me off to the market again?” the pike asked in a strong northern accent. I was too flabbergasted to say anything. “Why can’t you just leave me alone, you pest? How many more times? I’m just getting settled, just snuggling down for a bit of a rest and a doze—and out she pulls me! I’m not a fit young thing any longer; I must be older than you are… and my gills are giving me trouble too…”

It was strange to watch the way she spoke, exactly like a pike in the puppet theater—the way the opening and closing of her sharp-toothed jaws coincided with the sounds she pronounced was very disconcerting. She pronounced that final phrase with her jaws clamped shut.

“And the air is bad for me,” she went on. “What are you going to do if I die? It’s all because of your stupid, peasant meanness… always saving, but you have no idea what you’re saving up for… Got your fingers badly burned at the last reform, didn’t you. Oh yes! And what about those old hundred-ruble notes you used to paper the inside of your trunks! And the Kerensky rubles! You used the Kerensky notes to light the oven…”

“Well, you see…” I said, recovering my wits slightly.

“Ooh, who’s that?” the pike said in fright.

“I… I’m here by accident, really… I was just going to wash up a little.”

“Wash up! And I thought it was the old woman again. I can’t see too well; I’m old. They tell me the index of refraction in air is quite different. I ordered myself some air goggles once, but then I lost them and I can’t find them again… But who are you, then?”

Читать дальше

![Братья Стругацкие - Путь на Амальтею. Стажеры [сборник; litres]](/books/34218/bratya-strugackie-put-na-amalteyu-stazhery-sborn-thumb.webp)

![Братья Стругацкие - Путь на Амальтею. Далекая Радуга [сборник litres]](/books/388671/bratya-strugackie-put-na-amalteyu-dalekaya-raduga-thumb.webp)

![Братья Стругацкие - Улитка на склоне столетия [сборник, litres]](/books/420353/bratya-strugackie-ulitka-na-sklone-stoletiya-sborn-thumb.webp)