I was locked into her skyward gaze, thinking of the Simons, and the children staring at us with lapidary stillness so that we would go away, so that we wouldn’t see what was to occur atop Doug Sahm Hill.

The next comment Mr. English had made at the top of the page was: When are you going to let me submit that story of yours for you? And so here’s where it gets weird. It’s something I haven’t told you yet. I dunno, I just haven’t wanted to yet. Besides, this is the proper place in the story to do it.

So, the other thing Mr. English had said to me in his office when I went to pick up the essay, which was really a ruse to hang out because he could’ve just left it in my cubby—with the door closed, which he never did, this stricken, beset look on his face—was that these sorts of stories are popular right now. That’s not weird. What was weird was his tone which was low and careful like he was talking to a seething school-shooter holding Mommy’s M-16 Bushwacker.

He had continued, “People in general are fearful of what’s coming next. You can feel it in the air, Kevin. This apocalyptic vision of yours is not only well-written, sounding like something written by a seasoned writer, it’s something people are actually going to want to read, maybe even talk about.” A tight smile broke onto his face. “You could expand this and write a series of stories, which, if this quality were to be maintained… I wouldn’t be surprised if it saw a little serialization. They could even end up being fixed up into a novel.”

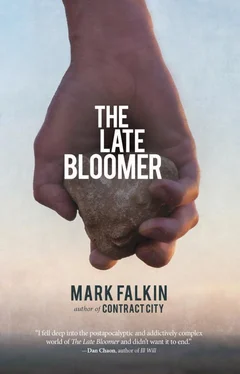

That’s not so weird either. What’s weird is the story’s existence in context. The short story which I called The Late Bloomers is a story about the end of the world. Three thousand words. Not so weird. But in it—here’s the thing—all the adults died leaving only the kids. What killed everyone was a virus like bird flu meets H1N1, and it took a while, more than a morning. But the story wasn’t about the virus and how it all went down or anything like that. The story was a snapshot of the aftermath, how the humans—a specific group of people I placed in Phoenix, who were eighteen, nineteen, who were adults but they weren’t—were dealing with it. The story ended elliptically but it seemed clear that the children and the late bloomers, the young adults who didn’t die because they still had kid in them, were going to rebuild the world together. The late bloomers would take the lead because the world needed the kid in us to remake the world.

I didn’t see it as good in the way Mr. English did. I mean, I was shooting for Carver realism and got this whacked-out end-of-days story. I guess that’s what happens when you uncork your mind and let the subconscious roam about.

It’s one story of several I’d shown him, but it was the one about which he gushed.

So, you get my queasiness now? I just wrote this story over the summer. I had given it to Mr. E in August. Right before my big pot bust was when he’d mentioned it to me. When I dropped by to pick up my No Go essay.

He was so keen on the story. The way he acted when talking to me about it, treating me like some sort of clairvoyant. He’d handed me the essay but held the story in his hands and he stabbed the paper with his index finger, saying, “There’s something here.” He gave me an accusatory look.

That’s when he’d moved past me to close the door. When it closed, the room got cottony quiet. I realized just how stuffed with books his office was.

He sat on the edge of his desk and looked down at me. His eyes said sit. I sat.

I set my backpack in my lap as a buffer between me and him.

I wouldn’t say he scared me then, but he wasn’t the flip and comely rake of a teacher with bedhead hair, chunky glasses, and a half-sleeve of tats I was used to. Here sat a man with curiosity, wonder, and, I detected, fear in his eyes. The look in one’s eyes you only see in dreams.

Like the one I’d had before I wrote that story. I popped up at 3:30 a.m. to write it.

I’d gotten to know Mr. English this fall, he being both my AP English teacher and my advisor. He’d requested that I be his advisee because he’d been on the Austin library’s poetry contest judging panel last April—National Poetry Month—and he’d read the poem I’d entered. The poems were submitted anonymously. I thought it was just this tiny contest. Well, mine, a not-half-bad free verse thing called My Unstrung Heart, Won’t You Please Be Still? , ended up winning in the high school category. It turned out to be not so tiny a contest. Mr. E read the poem aloud on the radio after Garrison Keillor had finished this especially glum delivery of a Galway Kinnell poem, The Silence of the World , concluding his radio segment The Writer’s Almanac .

Was Galway Kinnell one of my favorites? Yes, he was. You could even say he was my favorite. Was it neat-o that it was read right before mine, my poem rubbing elbows with his? You bet.

Given the tenor of this particular tale I’m telling you was the whole thing kissed by kismet in that now the aspect of this new world that makes my balls recede inside my body cavity is its silence and that Kinnell’s poem, coming right after mine, had that as its subject matter, indeed, bore the very title? Uh-huh. Yep. You’re catching on, dear reader.

Coincidences? Patterns? Early-onset schizophrenia? Psychosis? Grandma Lucille, what say you?

I know, I know.

So, anyway, you’re sitting at the edge of your desk, Mr. E, staring me down like I’d done something wrong, holding my story, touching the pad of your index finger to it saying, ‘there’s something here.’ You ‘couldn’t put your finger on’ what it was, yet you kept putting your actual finger on it. Kept making little circles on it with your index finger like a conjurer. My eyes flicked to your desk’s nameplate: Todd English, PhD (with such an education, why were you teaching high-school, Mr. E?), then to the framed black-and-white photograph of you and that smoking-hot wife of yours—Inga? Inger?—sitting on a boulder atop Mount Bonnell. My eyes stayed there. I hadn’t noticed the picture before. I started to lift my hand to point at it when you said, “Yeah. That’s new. We got engaged at that spot.”

I kept staring at it, looking at the transect of lake way down below you, and the strip of lawn where the bald man had stood waving up at me with that sickening smile.

I looked at your wife’s face. Intimidatingly beautiful with her square jaw, all blond Swedish model-looking. Real breasts, clearly. I couldn’t help thinking of her swanning around your house in one of your T-shirts post-coitus sipping on a bottle of water imported from her native Nordic country. I knew you didn’t have any kids. Fetching couple that you still were, I knew you’d probably be too old to conceive. You were the type who wanted kids. I knew it by the way you were, Mr. E. I thought maybe the pain and frustration I sensed in you wasn’t because of the shelved novel but the baby who wouldn’t come.

“Kevin? About this story. You said you’d had a dream?” you’d asked.

My eyes shifted from the photograph to your face. “Yes.”

“If you don’t mind my asking, what was the dream about? I’m not trying to analyze you or anything. I’m fascinated.” Your finger still on the paper.

“Well, you were in it,” I told you.

You sat up straight and cleared your throat. “Okay.” You sat back on the edge of your desk and crossed one leg over the other, furrowed your brow and nodded.

“Not until the end though, and your appearance didn’t connect to the rest. It was basically… what you and I are doing now. You, sitting on the edge of your desk looking as you do now, and me sitting here with my backpack in my lap.”

Читать дальше