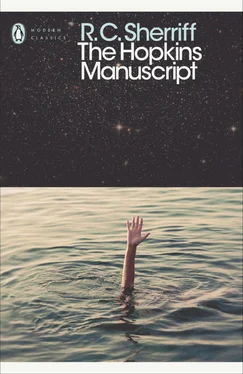

Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, humor_satire, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopkins Manuscript

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:978-0-241-34908-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopkins Manuscript: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopkins Manuscript»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopkins Manuscript — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopkins Manuscript», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It can readily be understood how this torment of mind and sudden, unexpected relief had blurred for the moment the significance of what the President had been talking about. I could scarcely be expected to care what happened to the moon so long as my fortune was saved and my enterprise vindicated.

It was not until the President had taken his seat that I began to realise the significance of this new turn in affairs. If the moon returned to the earth, or disappeared into space, the telescope would be a pure waste of money. It was just the kind of thing that would happen, I bitterly reflected. How was I to have known that by the time the telescope was delivered by the makers there would be no moon to look at? It was scant consolation to tell myself that this was a pardonable miscalculation that even the biggest astronomer might make.

I was upon the point of rising to ask the President what the Committee was going to do about the telescope when my attention was attracted by something that was happening around me.

It was as if a monkey wrench had been thrown suddenly into the wheels of time. Time had stopped dead, and every one of those men around me sat as if embalmed for all eternity. There was not a sound. The fat man beside me had apparently ceased to breathe, for the whistling intake and exhalation through his effective nostril had died away. I stared at the pallid, rigid profiles around me, and it seemed as if death had already brushed its fingers across those stark cheekbones.

And in that icy silence the terrible meaning of it all crashed into my brain and sent it reeling for support.

Many a time, in moments of morbid reflection, I had pictured this mighty, uncontrollable earth of ours plunging through space like a great liner ploughing at full speed through the dense fog of an iceberg-ridden sea. Always I had shuddered away from the thought of a ghastly collision with some dead, roaming world and applied my mind to healthier things.

And now – if this were true – if this meeting and these words from the President were not the twisted ravings of a nightmare, the horror was in fact staring us in the face.

A mighty mass of dead, ice-cold rock – three thousand miles in thickness and two thousand million tons in weight – was plunging towards us through the night.

No one could stop it. Death was facing us, and something worse than death. For always I had believed that when I died, the unquenched vitality of my body would mingle with the reservoir of life-giving power that lay within our atmosphere – to be used again and again to give animation, intelligence and happiness to living creatures for ever. My body would die but my life would survive, and now the horror that was approaching us would blast the earth to fragments. It would not only destroy our flesh and bones but would swirl this glorious life-power into the blackness of eternity.

The lecture room, with its tawdry, glaring lights – the President resting in his chair – that audience of rigid bodies – all become unreal and hollow – a cheap tin toy that tapped against my brain and set my teeth on edge.

Out of the silence came a tiny voice: the distant, quivering voice of Humphrey Tugwall, our Secretary. He rose to his feet and I stared at him. I knew his face, but I could not remember his name – nor his purpose in life.

‘The President will answer any questions,’ said the voice.

And then, without warning, came the incident which I think restored to all of us the knowledge that we were facing reality. And indirectly it restored to us our courage and control.

A small, sharp-featured man with dead white face and mop of black, dusty hair, sprang up from the back of the room and began to shout in an almost incoherent voice. Out of the babble of cascading words I caught remnants of coherency:

‘It’s all this damn monkeying that’s done it,’ he yelled. ‘All this damn monkeying with wireless and television and radio and aircraft rays! – I said it would! – you can’t monkey with things eternal and get away with it! – all this bloody monkeying with…’

The President had risen. He had taken up the small ebony mallet that lay beside him: he tapped sharply upon the table and the hysterical little man collapsed with a strangled sigh. There was something symbolic and exalting in those three sharp knocks upon the table: the first skirmish of reasoning courage against panic and disruption: courage won and panic collapsed.

‘Questions were invited,’ said the President. ‘No good can be served by useless proclamations. I would ask Members not to speak too loudly: the walls are thin and a women’s welfare club is meeting next door.’

There were murmurs of approval – even a ripple of laughter – and with it the tension snapped.

It eased rather than snapped, for the action of one of our number in rising and making an exhibition of himself did us all a power of good. It had been another man and not ourselves who had shown himself the coward. The terror of that little black-haired man had made the rest of us brave.

There came the rustling of a hundred bodies relaxing in their chairs. Someone lit a cigarette: someone cleared his throat, and a soft whistling beside me showed that my neighbour’s unobstructed nostril was at work again.

And then, as if further to bring us back to sanity, came the clear, jovial voice of Dr Perceval. He stood up, jingled a few coins in his pocket, and spoke as if he were opening a discussion upon the Butterflies of England.

‘I am sure that I voice the feelings of all members of this society when I tell Professor Hartley how much we have admired his courage, and his ability in placing this matter before us so clearly and calmly.’ He raised his head and spoke directly to the President. ‘You have given us, sir, a fine example, and I hope we shall prove worthy of it.’

Professor Hartley inclined his head in acknowledgement: there were some subdued ‘Hear – hear’s!’ and a little applause that died away directly Dr Perceval spoke again.

‘I would like to ask the President a question. It may be a futile question, but I think it is one that lies in the minds of all of us.

‘To what extent can the President give us hope? What hope is there of the earth surviving? What hope is there of life surviving? I realise that hope under such conditions is not easy to discover – but even in the gravest peril there must be a loophole for it.’

The President rose from his chair.

‘Thank you, Dr Perceval,’ he said. ‘I expected that question, naturally. I did not refer to this in my speech because I felt it better to confine myself to fact and leave theory and conjecture to discussion.’

Without conscious intention Professor Hartley gave proof that this question was expected by drawing towards him some notes which he had not yet consulted. He glanced down at them and proceeded.

‘Science, as you may well guess, is divided upon the question whether the earth can survive this concussion, and if so, whether life in any form can survive. There are those that believe that the explosion and destruction of the earth is inevitable. This I might describe as the “official” view. The earth, as you know, is no more than a stout crust that encases a furnace of molten rock. It is generally believed that the impact of the moon will split the earth to such an extent and to such a depth that this subterranean furnace will explode and blow the cool outer crust of the earth into fragments. Or it may burst from the ruptures in the earth’s surface in the form of great ridges of volcano. Upon this theory the earth may become as it was in the beginning: a ball of fire that in the course of eternity will once again form a crust upon which life will begin afresh.

‘Another school of thought led by the great German scientist, Franz Mulhause, believes that the moon may strike the earth a glancing blow and ricochet, as it were, into space again – once more becoming a satellite of the earth or vanishing altogether into the limitless spaces of the universe. This view is based upon the theory that the moon is not being drawn back to the earth by magnetic power: that the moon, for reasons unknown, has been forced from its normal path and is not necessarily bound to strike the earth a fatal blow. This theory may sound fantastic, but we are facing fantastic problems.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopkins Manuscript» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.