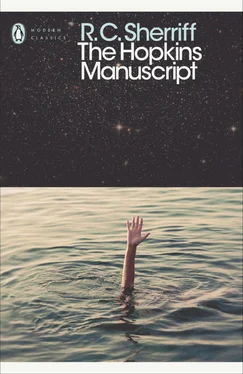

Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, humor_satire, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopkins Manuscript

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:978-0-241-34908-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopkins Manuscript: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopkins Manuscript»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopkins Manuscript — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopkins Manuscript», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But the strange thing is this. The news of the fantastic, ownerless wealth within the moon was the signal for a horrid swarm of political upstarts to appear in every nation of Europe. Some were fanatics devoid of all powers of reason and common sense, but most of them were worthless adventurers, greedy for wealth and power, their only claim to attention a loud voice and endless cascades of words.

These nasty creatures would swoop down upon peaceful, hard-working communities, upon people intent only upon rebuilding their shattered fortunes and living in quiet happiness. With clever, impassioned speeches they declared that their cowardly Governments were allowing other countries to seize the lion’s share of the moon’s wealth. They frightened bewildered people into believing that if they did not arouse themselves and ‘stand up for the rights of their country’ they would soon be living in poverty, slaves to a foreign power.

The quiet, hard-working men of the original Parliaments, exhausted already by their incessant labours, were no match for these maniacs and noisy upstarts. One by one, in different ways, the Governments fell, and with their passing the doom of Europe was sealed.

But I am wandering into the very trap that I have resolved so firmly to avoid. I am speaking of politics, and politics are no part of my story. Even had I the ability, I have no inclination to unravel and describe the network of intrigue – the cesspits of political chicanery that marked the Years of Decline.

I resolved, from the beginning of my narrative, to tell the story of these days as I saw them with my own eyes and I shall do so until the end.

When I awoke on the morning after Dr Cranley’s party I found myself living once again the emotions of an autumn morning two years ago. My reactions were very similar to those after the meeting of the British Lunar Society, when the approach of the moon was first made known to me.

Once again I was drowsily, uneasily conscious that something unpleasant had happened: once again I tried to persuade myself that it was no more than a dream, and then, when at last reality forced itself upon me, I began to persuade myself that it was just a silly scare and that nothing serious would happen.

But this new menace was so different – so sordid compared with the menace of the approaching moon. Despite the horror of it, the news that Professor Hartley gave to our Society upon that other night was too fantastic to be sordid: it had carried a spice of romance with it: a breathless excitement – a secret and a mystery that had chilled and yet enthralled me. The approaching moon had been so remotely beyond human control that it drew humanity together in a bond of ennobling courage.

But what thrill was there in the menace that stalked us now? – the menace of human greed and suspicion? The thin, brittle crust of prosperity that we had built over the ruins of the cataclysm would never stand the weight of human strife. Under the strain of war it must collapse in unspeakable chaos and misery.

I feared my fellow creatures far more than I ever feared the moon. The crisis of the cataclysm had been calculated to a definite day: a definite hour. We knew that by the 4th of May it would all be over one way or another: that we should die or live. But who could measure the suspense – the awful possibilities of war with every nation at the throat of its neighbour? – a war that could only end in the slavery of all to the tyranny of a solitary victor?

As I dressed in the pale sunlight of that autumn morning I whistled a tune from The Mikado : I whistled away the menace of the previous night and ran cheerfully down to breakfast determined that Major Jagger and his mad stories of approaching violence should be treated with the contempt that they deserved.

At breakfast Pat and Robin were quiet and thoughtful: it was natural that their young and impressionable minds should be affected by what they had heard, and I wasted no time in debunking Jagger with a vengeance.

‘The fellow’s a menace!’ I declared. ‘If he goes about talking as he did last night he ought to be locked up! Does he imagine anybody’s mad enough to fight over a gift from God? – there’s tons of moon – millions of tons of it: more than enough for everybody!’

Pat murmured agreement and poured out my coffee, but Robin was unconvinced.

‘Of course, it’s mad to think about fighting one another when we’re all just getting on our legs again. But it’s difficult. I never realised how difficult it was. I’ve been thinking about it all night.’

‘You’ve allowed a thing like this to keep you awake?’ I exclaimed.

‘I should have thought it would keep anybody awake,’ retorted the boy. ‘Look here…’ He drew from his pocket a sheet of paper, and I saw that it was a sketch, drawn from memory, of the map which Jagger had shown us on the previous night. To my alarm I noticed something of Jagger’s voice in Robin’s as he spoke: something of Jagger in the abrupt, decisive way in which the boy laid his map upon the table.

‘England, Spain and France are the only countries with a direct contact with the moon. Norway and Sweden might get to it around the north of Scotland, but how are the central European nations going to do it? How can Germany and Poland and Italy get to their provinces on the moon without passing through France and Spain? D’you suppose France and Spain will allow that?’

I had not thought of this. I looked at the map with a sudden loss of appetite.

‘How can they do it?’ demanded Robin.

‘The big question at the moment,’ I replied, ‘is how we shall get our wheat and potatoes to Mulcaster Market. Shall we hire the Municipal lorry and do it in one journey, or run it over in half a dozen journeys with the old Ford?’

I was afraid the boy would be angry at this bold and impudent change of subject, but instead his eyes lit up, and he laughed.

‘You’re right, Uncle,’ he said. ‘Let the politicians look after the moon and we’ll look after the farm.’

I went out to my morning’s work, happy and reassured. Even if men were mad enough to fight about the moon, their insanity could never harm us here. The air was fresh and keen: the first frost of autumn was sparkling in the meadows and the threat of danger, remote though it was, acted as a spur to my pleasure in the happy scene before me: to my pride in our achievement. The threat of danger gave me a fierce, triumphant determination that, come what may, our little estate would stand inviolable.

I thought of this valley as I had seen it in the grey dawn that followed the cataclysm: the hideous wastes of slime and destruction: the hopeless ruin of it all – I looked upon it now with renewed wonder.

The muddy silt of the tidal wave had given new heart to the land, and in the spring the grass had broken through richer and more verdant than ever I had seen it. The hillcrest, swept bare by the hurricane, was already speckled by stripling trees sprung from the shattered roots of their fathers. Stretching for two broad acres beyond the house lay my vegetable garden with its strong green ranks of cabbages and leeks, celery and turnips, with its reddish haze of sturdy rhubarb in the background.

We now employed a boy named Jim: a good, willing boy who gave alternate days to me in my vegetable garden, Robin in his rabbit and fish preserves and old Humphrey in the farm beyond The Manor House.

We were far more than self-supporting now. We sent regular and increasing supplies to Mulcaster Market and were accumulating a nice little credit with the new National Bank that opened in the summer. From this credit we bought new houses for my poultry farm, also our most prized possession of all, a cow and a calf. Humphrey had cleaned out and repaired the old dairy of The Manor House and Pat became expert at butter making. She was even experimenting, under Humphrey’s direction, in the art of making cheese.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

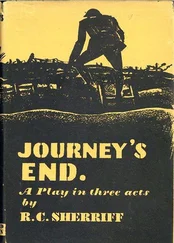

Похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopkins Manuscript» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.