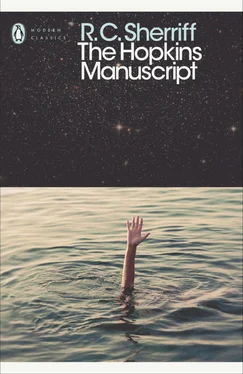

Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Роберт Шеррифф - The Hopkins Manuscript» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: sf_postapocalyptic, humor_satire, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopkins Manuscript

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:978-0-241-34908-3

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopkins Manuscript: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopkins Manuscript»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopkins Manuscript — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopkins Manuscript», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It did not occur to me that this all-important world of ours was one of a thousand million worlds eddying in the great hive of the universe. It did not occur to me that God had an intense, burning interest in them all – that even as we seethed and strutted on our own little earth, God might be planning and creating life upon a million others. If two of His thousand million worlds were to collide and destroy each other there was no special reason why He should be more concerned than I should be if two specks of dust ran into one another in my breakfast-room when Mrs Buller was sweeping the carpet.

But these thoughts have come to me only in the bitterness of the past seven years. Upon that sunlit autumn morning I am afraid my vanity persuaded me that God would never permit the world to end until I personally had finished with it.

Anyhow, the principal fact remained that I was a bachelor aged forty-seven, of set habits and comfortable circumstances. Even if I had wanted to, I could not have altered those habits upon my own accord. It needed more than a mere threat: it needed a complete, head-on collision with the moon to alter what I considered to be my rightful mode of life. The Burhampton Poultry Show was on Saturday and I had a reputation to keep up. I had entered six handsome Wyandotte cockerels, and my first duty after breakfast was to remove their portable run (with the assistance of Haggard, my gardener) to a clean spot in the meadow where they could benefit from the sweet grass and nutritious insects that infested it.

It was a magnificent autumn morning of crisp sunlight and refreshing north-west wind. As I worked with my gardener, Captain Alec Williams, the riding master, came along with one of his grooms and a waggon to stack a load of grass.

I had an arrangement with Captain Williams by which he paid me four guineas a year for my meadow grass, he being responsible for scything and stacking it in a corner of the field and collecting it as necessary. He paid me half-yearly, in June and December, and it occurred to me, as I watched him at work, that if the worst happened on the 3rd May he would get four months’ grass for nothing.

I did not resent this personally, but knowing what an honest man he was I realised that he would never forgive me if I allowed him to die in my debt. I decided to drop him a line suggesting that he paid me quarterly, so that his guinea upon the 25th March would practically cover the grass to the end.

It is remarkable how quickly a fine sunlit day can dissolve one’s cares. As the morning drew on and the sun grew warmer, and the bracing wind blew away the remnants of my headache, I found the trouble about the moon receding right into the background. For ten minutes at a time I completely forgot about it, as a man working in the sunlight of a garden around a haunted house might forget the ghost within until the shadows lengthen across the lawn.

I had a half-bottle of my favourite claret for lunch, and as I sat smoking a cigar and reading The Times beside my fire I felt prepared to argue against the greatest scientist in the world that the whole business about the moon was an absurd hoax – that everything would be all right and that I should continue to enjoy life upon my little estate for years and years to come. It was too absurd to believe.

During the afternoon I had one difficult moment when Haggard, my gardener, was helping me to clip my shaped yews. Without any warning he asked me whether my meeting had gone off all right on the previous evening.

It was upon the tip of my tongue to tell him that it had gone off quite unexpectedly: gone off, in fact, with a considerable explosion, when I remembered my oath and replied lightly that it had been a pleasant meeting at which we had discussed the action of the moon upon the tides of the ocean. It was my first lie for the sake of humanity and I was pleased with it.

He asked me whether the tide went out further at Southend than it did at Brighton because Southend was nearer the moon. I replied that this was no doubt the reason and tactfully changed a subject which I did not wish to pursue by making a suggestion concerning the shape of one of my yew trees.

When I had purchased Beech Knoll five years ago, the yew trees lining the path to the front door were trimmed into the shape of rabbits sitting up on their hind legs. By carefully training and clipping each summer I had altered these figures into hens sitting upon nests. I had achieved this by allowing the lower portions of the rabbit to bush out a bit (to form the ‘nests’) and by training a small piece of foliage in each tree to resemble a hen’s tail.

I now suggested that in one tree, as an experiment, we might entirely cut away the foliage that formed the nest, trim down the base until we had two parallel stalks, and so make a very passable gamecock.

Haggard agreed enthusiastically, but in doing it we had the misfortune to cut the stem that supplied the foliage for the head. We had no alternative but to trim the tail into a head, with the disappointing result of what appeared to be a small fat man with his trouser legs turned up, paddling in the sea.

Those who know the slowness of a yew tree’s growth will realise what this meant. For years I would be forced to look at this grotesque monstrosity and explain it away as best I could to my friends. My nerves were no doubt upon edge and I am afraid I lost my temper when Haggard suggested trimming it neatly all round and having a cannon ball.

‘Leave it alone!’ I said. ‘Let it grow out and we’ll do what we can next year.’

Even as I said the words I felt a sudden, sick bewilderment. It needed something definite, something intimate like this mutilated yew tree to give me a full sense of proportion. Yews were late starters and seldom made new growth until mid-May or June, and there was never to be another May, or another June. The old trees stood before me – olive green in the fading light: for five years I had known them as the faithful, unsleeping sentinels that lined my path – that greeted me in the morning and rustled a ‘goodnight’ to my bedroom window. And now they were over. Most of my trees would have awakened from their winter sleep and clad themselves in a sheen of delicate spring leaves to meet their death on the 3rd of May – but my yews were ended for ever – they had thrown out their last green tips of growth this summer and were doomed never to grow again: the end would come before the spring life stirred in them – they would die in their sleep… it was bewildering, and horrible…

‘You all right, sir?’ enquired Haggard.

‘Of course I’m all right,’ I snapped. ‘Why?’

‘You’re looking quite pale, sir. Turns cold quick in this wind at sundown. Better be careful of chills, sir.’

I was angry, and made no reply. Haggard apparently thought me a weakling – chilled by a puff of wind. How quickly his contempt would have changed to wonder had he known the truth! – had he known the awful reality that I had faced with no more than a passing paleness!

I had been very proud of the terrible secret I had carried away with me from our Meeting: proud of the trust reposed in me – proud of my supreme knowledge over ignorant millions, but steadily my pride was turning to impotent annoyance. What, after all, is the pleasure of holding within oneself a colossal, awe-inspiring secret when nobody around one even knows that you are keeping it? No more good than a brave smile to hide a toothache when nobody knows you’ve got a toothache!

I had no heart for further work. As I glanced up from my darkening yew trees I saw that the sun was setting, and once again there had crept into the sky that pulsating, rusty glow. I felt utterly miserable as I watched Haggard striding down the hillside with an armful of tools. Out in this carefree, sunlit garden I had been able to cast aside my thoughts of dread reality, but the beauty of this dying autumn day was making more horrible the knowledge that never again upon this earth would there be another summer – never again a haze of violet blossom in May – never again the spangle of June roses.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopkins Manuscript» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopkins Manuscript» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.