They looked at the map under Doyle’s meaty hand. They looked at each other over the folded borders of their scarves—brown eyes, blue eyes, muddy hazel.

“How can we know that?” asked one of them. He was young, nineteen or twenty, and when everyone turned to stare, the tops of his freckled ears flushed dark red.

“We have intelligence,” said Doyle in his rumbling, bottomless voice. “Unlike yourself. Save your questions, cubby. Shut up and learn.” A few uneasy chuckles rose and fell. “They have a small head start, but they have impediments that we don’t,” he said. “An old woman. A young one who doesn’t know shit about rough living. A dog.”

Russell stood and leaned over them, both hands on the table. The skin on his left hand was a map, too, one made of grisly interconnected scars. “We’re going to take them,” he said. He spoke softly and the indigo wrap helped muffle the speech impediment caused by his wounds. “Every single one. Take them, and deal with them.” He put his hands behind his back and let his good eye linger on each face. “Including the dog,” he said. “Believe it.”

THE SOUND OF RAIN. Shivering, her shoulder and back on fire. Renna coaxing, Drink this, Arie. Drink. Water. Broth, the taste of bone marrow. Sleep. Dreams of her sister Mercy, crying at the south gate as Arie walked away. A crackle of flames, then Handy, You’re safe, Sister, it’s only to cook on. Sweet brown eyes, cold nose, heavy pelt—Talus watching, licking her hand, stretched out along her side. Outside again: lying in Curran’s arms, lying on a gently bouncing stretcher, trees like cathedral spires far overhead. Inside, somewhere. Curran singing, There is a ship that sails the sea, she’s loaded deep as deep can be. Smell of mildew and mouse turds. Raised voices, men’s voices, Yes, but if we’re caught out in the weather. Renna with a soft cloth, washing her like a baby. Dreams of Granny in the bed with her, We won’t go anywhere.

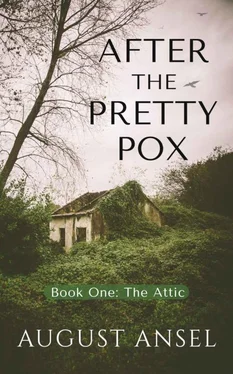

One morning, there were birds. Arie opened her eyes. She was in a bedroom. In a bed. The room was large, beautiful. Next to the bed were French doors that let out on a deck. The glass panes, though cloudy with dirt, offered a grand view of the trees. Narrow ribbons of morning sun stabbed through the branches.

A Steller’s jay landed on the deck rail. He cocked his dark, crested head in several directions, hopped down onto the deck floor. He pecked at the piled needles, cones, and leaves, his plumage an otherworldly blue. Another jay landed, and they squabbled in their raucous way. On the floor next to Arie’s bed, Talus lifted her head to see what the trouble was. She stood, stretched deeply, and stepped over to the French doors. One of the birds flew onto a nearby branch, but the other hopped brazenly about, keeping an eye on the dog behind the glass.

“Hey,” said Arie. Her voice was a dry whistle. Talus looked and grinned her doggy grin, tongue out, big tail swinging. She came to the edge of the bed and stood. This put them eye-to-eye. “Aren’t you a great good thing,” said Arie. Talus put her forelegs on the bed and rested her muzzle on the mattress, looking out from under her black eyelashes. Arie reached, ran her palm over the silky face. The bad spot on her back was stiff and painful, as if some terrible thing would crack open if she moved too much. Talus let herself be stroked, and then she surged forward to give Arie a vigorous face-licking. She bounced off the bed and pushed open the partially closed bedroom door. In a moment, Arie heard Curran murmur. Talus barked once, twice, and Curran came shuffling into the bedroom, squinting against the sun now streaming across the floor.

“Hey,” he said. “Is that you in there?”

“Still here.”

He shook his head and smiled. “Your life is still your own.”

“So it seems. Water?”

“Yep.” He bent and kissed her cheek. “Be right back.”

“Handy and Renna?” Arie rasped.

Curran stood at the door in sock feet, scratching the back of his head. His black hair had grown and mostly covered the place where she’d stitched his torn and naked scalp. His face was clear of all the residual bruises. Beyond the fact of healing, he looked changed to her. Older. “I’ll get your entourage,” he said.

For two weeks Arie’s fever had run its course. Handy found chamomile and plantain in the ditches bordering the long gravel driveway that meandered up from the road. Renna bathed the burn in cool tea and gave it air until it scabbed over, then she covered it with plantain poultices, exactly as she had seen Arie do for her own dog bites. It had likely saved her.

Everything Arie knew now about those bleary, half-conscious days after the fire, she’d been told by the three of them, starting on the morning she woke up with Talus.

They had fled to Curran’s house in the stump and stayed for two days, waiting for the first break in the rain. There were still a few usable items inside the place; the tarps and fabrics he’d used to cover the floor served to make Arie’s stretcher. During those couple of days, both men had gone out under cover of dark, more concerned with human threat than with lion or bear. Back at the burned-out house, they had scavenged the black wreckage. The bodies of the two dead men were still there, picked over much as the wild dogs had been—scattered bones, torn and bloody clothing, a featureless skull wearing hair and an orange beanie.

“It was Little Mikey,” Curran said. Telling this part, his face was more miserable than Arie had ever seen it.

“I thought as much.”

“I killed him,” he said. “Got on top and choked him.” He held out his hands as he spoke, visibly shaking.

“Thank you for that,” Arie said.

He balled his trembling hands into a single fist and nodded. “It was bad, seeing him like that, after—”

“No one came back for them.” Arie shook her head. “Gods…not even to make a burial.” She put her own hand over his two clenched ones and could feel his muscles thrumming. “Kings, my ass,” she said.

As for salvage, there was little left in the smoking wreckage. The hundred-year-old redwood timbers had made glorious fuel. The site was little more than a pile of jagged black jackstraws heaped around exposed lead pipes and various humps and twists of metal—the steel tool chest, kitchen appliances, Granny’s chrome dining table, the old hot water heater. But just as they were ready to give up and retreat into the woods, they stumbled across a wonderful thing: two of the three packs that Arie had made. While Arie had kept Russell busy from the roof, Renna managed to drag the packs down the inside hatch. She’d stashed them in the useless bathroom, which was nearly as far from the ignition point of the fire as it could be. Laid in the cast iron tub behind a closed door, the two packs ended up fully intact, no more the worse for wear than a great deal of smoke smell, greasy dark ash, and wet from the days of rain soaking through the rubble.

They were in a huge house, something a backcountry weed grower had commissioned far up a dirt road, lived in during construction but then abandoned—maybe a grow bust. Maybe the Pink. The finished area was a wonder, with its pale bamboo floors and natural stone fireplace. Those rooms boasted vivid hand-woven wall hangings from Guatemala and a display case of jade Buddhas, their milky translucent green so beautiful they were almost painful to look at. Nevertheless, depredation was everywhere. A falling branch had crashed through a bank of windows, allowing in all manner of weather and wildlife.

Читать дальше