* * *

When it was all over, when the attack was finally halted and the victory celebration by most had begun, the Younglings made a decision regarding their future with the colonies. Vic and Via, Kal and Tal, and less than a hundred others of both species requested an audience with the council Elders.

Though he dreaded it, Vic began the conversation that would change their lives forever.

“Council Elders Bongse, Magsay, Hettie, and Max. As you know, we council Younglings were opposed, for the most part, to your decision to eradicate the Humans. We feel that, with a little more consideration and a little more time, we could have found a better alternative, some other way to ensure the safety of the colonies. We feel that you acted just as the Humans of old would have. And by doing so, you’ve proven they were not the only creatures on this planet who are selfish and greedy, malicious and murderous.

“Your actions, whether you realize it or not, have doomed these colonies to collapse. You’ve planted the seeds of hatred within your own colonists, and before long these seeds will no doubt spring forth to kill all that you see, all that you now hold dear. The very thing you were so afraid of in Humans has now taken root in our own society—and that’s your doing. You have become the very thing you so feared and despised.

“I am ashamed—I am mortified—to have witnessed your act of barbarism against the Humans. I cannot be a member of a society that sanctions such slaughter. So it’s with a heavy heart that I must hereby resign from my position on the council. Kal also offers his resignation. We, along with the others in the colonies who agree with us, will depart immediately to begin our own colonies as far away from this tragedy as possible.”

The council Elders gaped, speechless, as Vic exited the meeting chamber followed by his sister, Kal, Tal, and the Bats and Budgies who would leave with them. None, not even the firebrand Bongse, could utter a word as they left.

Max seemed sad but resigned to Vic’s words. He knew them to be true. And a similar light of understanding was dawning on the faces of Magsay and Hettie. Understanding and loss. And a deep sense of mourning.

* * *

At daybreak the next day, the hundred or so new colonists began their journey to a new land and a new life. The Budgies would fly by day and the Bats would fly by night, each group meeting at sunset and sunrise to further plan their travels until they found a suitable place to settle down and begin life anew.

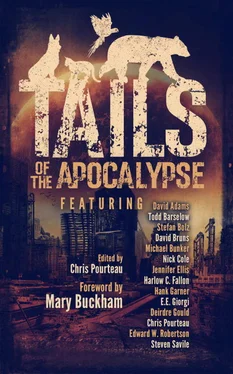

A Word from Todd Barselow

Todd with George and Tori.

I’m best known for my work as an editor who specializes in assisting independently publishing authors. I’m also known as the senior editor at Imajin Books, a small Canadian publisher, whose books are widely read and enjoyed around the world. All told, I’ve worked on more than 200 books in my career as an editor. I’m also the owner and publisher of Auspicious Apparatus Press, which produces quality fiction in ebook, paperback, and audiobook formats.

I’m a frequent contributor to Anne Rice’s official Facebook page and have been dubbed by Anne as a Pillar of the Page—one who frequently contributes content considered worthwhile by Anne.

I live in Davao City, Philippines, with my wife and four lovely little Budgie birds—Max, Charlie, Bleu, and Sandy. “Wings of Paradise” is my first published short story.

Ghost Light

by Steven Savile

They told us we didn’t need to be afraid of the Russians anymore. They told us that they were our friends. What that meant was that we neutralized each other. Mutually assured destruction. That’s not the same as friendship.

We weren’t meant to worry when they annexed the Ukraine, they said. That was just reclaiming what was already theirs. Most of the Crimea was still Russian in their hearts, if not their passports. That’s what they told us. They made excuses when the missiles first launched into Syria, a scorched-earth policy meant to burn the land and ISIS with it. Or IS or ISIL or whatever we called the terrorists back then.

Most of us just believed what we were told. The Russians were the greatest threat we’d ever faced. They were the scourge of the East. They were the root of all Evil—capital E evil, not the small stuff—but we weren’t meant to worry because our friends were on the case. Their missiles and bombs and guns would cleanse the world, and we’d line the streets and cheer when our boys came home from the front as heroes.

That’s what they told us.

Pity is, it was all a pack of lies.

I don’t remember when it all started to unravel. Maybe there wasn’t a single defining moment. We like to think of things in neat terms. We look for a tipping point, an Archduke Ferdinand moment, but sometimes life—and especially death—just aren’t that clean.

I’m part of an older generation. We were brought up knowing our enemies were big things with little names: diseases like AIDS and HIV, superflus and flesh-eating bacteria. We knew we were destroying the world with our CFCs and polluting it by burning fossil fuels. But we were selfish. We wanted to drive our Escalades and our muscle cars and didn’t give a crap about our carbon footprint. We were here, this was our world, our one life, and we’d damn well live it the way we wanted to.

And then the Russians changed everything.

It was hard to believe that some craggy-faced vodka drinker could actually do it—lean forward and press the button. But he did. It probably wasn’t how I imagine it. The end of the world seldom is.

I like to imagine him knowing exactly what he was doing, lining up some ridiculously expensive Cohiba cigar and a bottle of Stoli, a well-thumbed copy of Das Kapital beside them, the holy trinity for a Russian patriot. I can imagine him clipping off the end of the cigar and sucking in the smoke, puff-puff-puff, followed by a long exhalation as smoke rings drifted up in front of his face. Then he washes the taste out of his mouth with one last, perfect shot of vodka and turns to a passage in the good book that brings him comfort. Because it’s a big thing, ending the world. The act needs a certain resigned serenity to it, a certain ritual. I don’t want to think about power brokers in a nuclear bunker arguing about times to detonation, viable targets, and strategic strikes. I guess I want to believe it was a better world back then.

I know it isn’t a better world now.

I was one of the lucky few. Or the unlucky few, depending upon your perspective. I was airborne on a 747 flying from Munich to London. Going home. Only, it turned out, there was no home to go to. We watched the clouds rise like fungus from the earth, the nuclear winds battering the hull, forcing the pilot to rise higher. The shockwaves came again and again like tidal surges. Of the 418 passengers, 197 didn’t want to land. They argued it would be better to fly until the fuel ran out and hope the plane came down in the ocean because that was a fast death. That way we’d not have to watch what had happened to the world. Two hundred and twenty-one people refused to give up hope. Two hundred and twenty-one people damned everyone on Flight BA949.

We didn’t land at Heathrow like we were supposed to. The pilot took us north, banking up towards the Highlands of Scotland. We didn’t understand why he did that at first, but the Scots built their roads to function as emergency runways. So we could land on a remote strip well out of any city, away from the radiation and the sickness that threatened. We didn’t think about stuff like altitude and the cold or how tough it would be to scavenge food when our new world was frozen. We just wanted to hide from the worst of the destruction.

Читать дальше