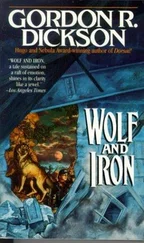

But Greta was indeed gone. Jeebee waited a little while for the fact to sink in, before he mildly offered a suggestion.

“I think she’s gone up into the woods to meet Wolf,” hesaid.

“She wouldn’t do that—” Merry broke off. She stared angrily at Jeebee. “Hell! Watch the stock!”

She wheeled her horse about and galloped up to the front of the wagon. There were a few moments in which Jeebee could hear a conversation between Paul and his daughter, but could not make out exactly what they were saying. The voices ceased and the wagon came suddenly to a stop. Merry came back to the tail of the wagon again.

“You make sure the stock stays together,” she said. “I’m going up after her and bring her back.”

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you,” said Jeebee.

She literally glared at him.

“You know, this is all your fault!” she said. “You and that wolf! Why shouldn’t I go?”

“Why?” Jeebee echoed. “Because if you start up there, Wolf is going to run away when he sees you coming. And Greta’s already shown that she’s going to follow him, so you’re likely to lose them both. You’d be surprised how hard it is to find a couple of animals like that if they want to get away from you and hide.”

He stopped. He felt sorry for her.

“It’s all right, you know,” he said. “As long as we leave them alone, she’s going to meet Wolf just inside the woods there and they’ll be together for a little while and then she’ll come back to the wagon. Just as Wolf doesn’t want to leave me, she doesn’t want to leave the rest of you down here. She’s simply being pulled two ways at the present moment.”

The nearest patch of woods was up a gentle slope and about two hundred yards away. Merry looked past Jeebee at it, stared at it.

“How long will we have to wait?” she asked. Her own voice was suddenly, surprisingly calm.

“I don’t know,” Jeebee answered. “But I don’t think it’ll be long. What I’d suggest is that you stop for maybe half an hour—long enough to have lunch, say—and if Greta hasn’t shown by that time, start to move off. She’ll have been with Wolf long enough to get over her first impulse to go to him, and when she sees you leaving, she’ll be afraid of losing you. I’m pretty sure then she’ll come out and follow—in fact I’m pretty sure she’ll catch up with us right away.”

There was a long silence. Merry looked back at him.

“It makes sense,” she said, more quietly. “Look, I’m sorry I snapped at you. You made it clear enough when you joined us that you couldn’t control that animal. I don’t mean to blame you for what he does, but maybe it’d been better all around if we’d shot him on first sight.”

“If you had,” said Jeebee, “I’d probably have shot at you. I mean that.”

For a moment their eyes locked, and somewhat to Jeebee’s surprise, Merry’s face relaxed, relaxed a little more, and finally smiled.

“He does mean a lot to you, doesn’t he?” she said. “I’m sorry. I spoke too fast. I wouldn’t really have shot at him, even then. At least I don’t think I would. Dad might’ve—but I doubt even that.”

She lifted her reins and pressed with one knee. “I’ll go talk Dad into stopping for a bit,” she said—and was gone.

To Jeebee’s surprise, Paul did not seem at all put out by the idea of a half hour or even an hour’s delay. He was discovering something more about the man who had built and operated this whole peddler’s scheme, and that was that he had a very lively curiosity about anything and everything.

There had been hints of this when he had been talking with Jeebee in the process of teaching Jeebee to drive the wagon team. Every now and then Paul would have a mild question about what Jeebee’s life had been like before he had headed west to find his brother’s ranch. At first these questions passed almost unnoticed by Jeebee as he answered them. Later, he began to realize that Paul was slowly and quite subtly drawing out of him his personal history. The questions invariably came after Paul had told Jeebee something about his own background, so that it was difficult not to reciprocate.

At first Jeebee thought that Paul was simply interested in what kind of man he’d picked up by the roadside. Then he began to discover that Paul was genuinely interested in the work of the study group. Jeebee tried to explain this in words that would be understandable to the other but Paul shook his head.

“Most of it I can’t follow,” he said finally, “but unless I’m wrong, what it all adds up to is that you saw this coming almost as early as I did and didn’t do a thing about it. Particularly you didn’t do anything to save yourself until you darn near got smoked out of your own home by neighbors that had set out to kill you.”

Jeebee nodded.

“Why?” Paul had said. “Why, when you could see it coming, wait like that?”

Jeebee hesitated. It was not that he did not know the answer. It was just difficult to explain. Finally, he shrugged.

“If you’re any good as a scientist,” he had said, “you have to learn a certain detachment from what you’re studying. If you don’t, it’s too easy to see what you want to see in the numbers. Anyone who studies social behavior has to learn to treat social processes and dynamics as pure abstractions that’ve got nothing to do with him personally. What happened in Stoketon was a truck that ran us down while we were still busy calculating, from its speed and weight, just how hard it could hit.”

He could hear his own words and they sounded a little stiff and academic in his ears. But they were all true—all what had actually happened.

The day was bright and warm, so that the little air stir resulting from their passage was pleasant. Neither he nor Paul said anything for a moment.

“You and this brother of yours pretty close?” Paul asked.

“Yes,” Jeebee said, and then hesitated.

He had never stopped to think about it, but he realized now that he had always thought of Martin as a sort of lesser and more distant father, lost somewhere behind the shadow of Carey, the actual father of both of them.

“That is,” Jeebee went on, “when we were younger. There’s eighteen years between us. He’s the older. I used to visit up at the ranch and he’d visit us—my father, my mother, and me—sometimes. After my father died—well, actually, after my mother’s death, when I was sixteen—we fell out of touch a bit; though we still wrote letters every so often. But I haven’t seen him since I was about—oh, fourteen or fifteen years old.”

“How come your father moved away from the ranch?” Paul asked.

“It really wasn’t what he wanted,” Jeebee said. “My grandfather did, and Martin did. But Dad really didn’t care for it too much. He stuck with it until the Vietnam War came along. He’d already had Martin, but he joined up and went off to the war anyway. He told my grandfather that he was giving up all claim to the ranch so the way would be clear for Martin in case anything happened to him while he was gone.”

There was another long pause as the wagon rolled and jolted on its way.

“Afterward,” Jeebee said without prompting, finding a sudden relief—almost a pleasure in telling this to someone, finally—“there was the GI Bill. He always liked architecture. So he went to school to become an architect.”

“Architecture,” Paul said thoughtfully, “a far call from ranching.”

“Oh, Dad was always a hands-on man,” said Jeebee. “He liked to build with existing materials. If he saw a rocky hillside lot, he’d immediately be taken with the idea of building a house with the rock. A house that would seem to grow right out of the hillside, there. An interesting piece of wood could give him an idea for pegged, instead of nailed houses—even log houses.”

Читать дальше