He came back inside and started blindly to go to work at finally opening up the ceiling above their heads. Merry stopped him.

“Have you no sense left at all?” Merry said. “You’re so close to being unconscious, you don’t know whether you’re standing on your head or your feet.”

He turned around to argue with her, and found that the movement made him dizzy. Subsiding, he let her pilot him back to the bed, and lay down on it.

“Just give me an hour,” he said, “then I can finish it.”

“Hour, nothing!” Merry retorted. “You’ve got us sealed in up there now. You’ve got all winter to take down the ceiling of this room. You sleep and just let yourself sleep as much as you can.”

He still felt that he should be arguing with her, but somehow the strength was not in him. He did not remember any more until he woke, finally, to find sunlight in his face.

He came to, startled, opening his eyes and sitting up on the edge of the bed at the same time. Above him the ceiling had been half torn down toward the front of the inner room, and daylight was streaming through and down upon them. There was a fire in the fireplace, Paul was silent in his crib, and Merry was busy sewing something at the table.

“You opened up the ceiling—” Jeebee said stupidly.

Merry bit off a thread.

“And I can do the rest of it without your help,” she said without looking at him. But her tone was soft. “Go back to sleep.”

He tried to stand up, found he was still dizzy, and lay back down on the bed. Sleep came again, at once. However, this time it was not a deep unconsciousness, in which he would even lose track of time. This time he dreamed; and it was the old nightmare that he had carried with him out of Michigan into northern Indiana and westward.

He dreamed again that he was working in the study group, and that the screen in front of him was full of the symbols of his equations. Suddenly a darkness, just a pinpoint of darkness at first, appeared near the middle of the screen to obliterate some of them. But it grew, spreading and wiping out all his work.

It was, as he had long since figured out, his consciousness of the Collapse, in retrospect coming to interrupt and destroy all that he had tried to do—he and the others. Again he dreamed of the black shape that pursued him, cornered him, over and over, looming closer and closer, to blot out everything as it came close to blot him out also.

He woke, sweating.

Merry was seated on the bed beside him, her hands on his shoulders. She had been the one who had seized him, not the darkness.

“You had a nightmare,” she said, relaxing her grip and letting him sag back against the pillow. “You were shouting—something about iron.”

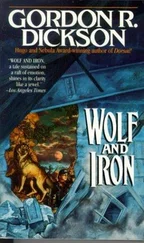

“The iron years,” he said dully.

“The iron years?” She looked at him narrowly.

“It was just my name for this time we’re in, that’s followed the Collapse,” Jeebee said. “That’s all. I thought—I told myself we’d gone back to the time of iron. You understand?”

Merry nodded her head.

“I think so,” she said. “You mean we’ve moved into a time when things are hard, when everything is hard, like iron?”

“That’s it,” Jeebee said, remembering even as he spoke to her. “Maybe a little more than that. I meant—you know, there was a time once when iron ruled the world. Men with iron weapons, in iron armor, ruled everything. And in some ways we’ve gone back to it now, and it will last at least for decades, maybe for a couple of hundred years—”

He broke off, looking up at her concerned face.

“Oh, we’ll go back to civilization, back to technology,” he said. “It’s inevitable. It won’t be exactly the same, but the knowledge’ll all be built up again. It’s always been that way.”

“Always?” said Merry. “This never happened before—the Collapse with everything falling apart, the whole world going bankrupt, transportation and communication and everything failing, all at once.”

“No,” Jeebee answered, “but that’s just the shape it’s taken in our time. Before that there was pestilence, or barbarians who took everything, including life, from all but a few lucky ones, and each time the race built back to get pretty much on the track it’d been on from the start. We’ll do it again. But it’s going to be a hard time, in between. That’s what I was thinking of when I started calling them ‘iron years.’”

She took a corner of the top sheet and wiped his damp face, gently.

“It’s my fault,” she said.

“Your fault?” Jeebee stared at her.

“Oh, I don’t mean the iron years. I mean, you overworked. You drove yourself to the dropping point. And that was my fault because I started you out by shoving you in that direction. I was so full of thinking what we needed for Paul through this winter. I should have known you don’t need prodding, that you’d go to your absolute limits anyway, without anyone shoving you from behind.”

“Well, then.” Jeebee reached up and pulled her down to him so that he could kiss her. “I would have done the same thing anyway then, wouldn’t I?”

“Maybe,” Merry said, laying her cheek alongside his, “but if you do, from now on, you’ll only have yourself to blame.”

Jeebee looked around him. There was a strange quality to the light coming down on them from the skylight. It could not be just that they were later in the afternoon; the angle of the light had not changed that much. He could have only been asleep another hour or so at the most.

“I’ve got to get up,” he said.

Merry’s hands pressed his shoulders softly back toward the bed.

“It’s snowing. Snowing heavily,” she said. “We’re locked in for a while. Besides, it’s time for you to do nothing for a few days and mend. Give yourself time.”

“Still, I—”

“No still,” Merry interrupted. “It’ll be hard to stop the wheels spinning at first, but you’ll just have to wait until they do. Now lie back, take it easy, do nothing; at least till the storm stops and probably for the next few days. We’re in no hurry, now. We’re sealed in, nice and tight and warm, the three of us. We’ve got plenty of meat and vegetables stored. There’s all the time in the world for us, now.”

She was right, of course. It took Jeebee a little time to admit it to himself, but the way he had collapsed physically before his first long sleep was something with which he could not argue.

He worked at resting. For the first two days, it was indeed work. He had to fight to keep from getting up and doing things; and in the end, about the third or fourth day, he did let himself finish opening up the whole ceiling of the inner room to the skylight. He also let himself do small things like bringing in wood to keep the fireplace fire going, and making sure the solar blanket was not covered by snow, but hung up against the front wall of the cave, where it could get the full benefit of the sun to recharge the batteries he had depleted during his last orgy of work.

Little by little, he relaxed. It did not come easily, but gradually the urge crying out inside of him to be busy, always busy, muted and fell silent. He reread his wolf books, he watched Merry, he thought, and above all he studied young Paul, sitting in a chair by the cradle and watching the baby, both asleep and awake, for long periods.

There was a healing element in this period. He could feel it, but the machinery of it did not come out into the open of his conscious mind until he felt Merry’s arm around his shoulder one day as he was sitting watching Paul and saw her gazing down at him.

He looked up at her.

“You know,” he said, “I told you about that moment I had with him during the birth, when his eyes opened? That moment of bonding?”

Читать дальше