Not Cima. She just screamed. Once. I shoved the yoke forward again, swung down the nose to near level, prayed for speed for speed, soon enough the Beast took it, accelerated like a swallow that swoops after veering upwards for a bug and we flew level at sixty five, I looked down at the trees, thought, If we cleared them by two feet.

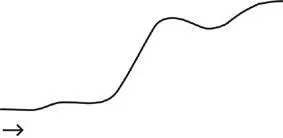

Not a regulation takeoff. Not in the book even for a short soft field. This is what our vector from the meadow probably looked like:

Well I must’ve been glad to be alive. I loosed a yell. The junipers rushed beneath us. The Beast rolled over the next ridge fifty feet over the trees, it seemed on her own volition, like a magic carpet. Coastered down the other side. One way to enter the next dream. She was beaming the way a small kid beams after surviving the magic mountain log flume at Six Flags. She reached over and pinched my arm.

We’re alive see? Nice work.

We’re awake.

You say the strangest things.

Even the lambs had caught the mood. They no longer cried, they lifted their heads off the packs and followed the conversation, floppy eared and guileless attendants. As far as they knew, all this represented the next stage in the normal life cycle of a sheep.

We crossed the big river and Pops was sitting on his pack like any hitchhiker on a shadeless stretch of desert highway. Something in his attitude at once resolute and refractory, pinned to his long shadow, the rifle standing between his knees like the staff of an acolyte. Which he was: bent to the mission, devoted now to a new life. If we could get there. The bandana fluttered on the mile post, barely registering the breeze of a calm summer morning. I banked left and landed and tapped the brakes to a full stop right across from where he sat.

He climbed in behind his daughter. Noah’s Ark, he said glancing at the lambs. That was all. Cima pulled the door shut, latched it and we took off to the west toward Grand Junction.

Something was not right. I won’t say wrong because how it registered wasn’t anything so definitive. Ten miles to the east I had made the first call. We had cleared the far cliffs of Grand Mesa, the great flattopped butte that looked like it must have been a peninsula in some shallow, plesiosaur haunted sea. A sixty mile long outcrop risen against the sky. It was banded with purple cliffs and covered with aspen forests. In summer they were waist deep with ferns and strung with dark lakes and beaver ponds. Melissa and I had shared some of our best camping trips up there, once tenting for a week on the edge of a lake with no road for miles and the trout just about jumping into our frying pan.

We had flown past it, beneath the rim, staying low to save fuel, the warm wind pouring through the empty frame where Pops had shot out my window, and there was Grand Junction, straddling the two rivers and sprawling over the desert hills. A vast gritty town that stretched all the way to the Book Cliffs to the north.

There were the highways, the streets, the developments, the cul de sacs, the flat blank roofs of the box stores, the vast parking lots. There was the industrial section along the Colorado River, the train tracks, the phalanx of warehouses. The city was threaded with cottonwoods. Many of the old trees that lined the streets and depended on watering were skeletal and dead but many were rooted deep enough and punctuated the thoroughfares with dashes and clumps of violent green like some Morse code.

The canopies of cottonwoods still shaded the river parks, some of the oldest and biggest fighting the drought just half dead, still clothed with leaves on one side. And fire. Not a corner of the city untouched. As if it had been fire not flu that had swept death through the town. The cars, every one it seemed, scorched. Where they were parked in the side streets in their rows, in mall parking lots, out on the highways, where they lay in such a chaos, such absence of pattern some giant might have thrown them like pick up sticks. Whole neighborhoods were burned to the ground. Others looked as if torched just to melting and left to cool the way a pastry chef glazes a brûlée. The sweet black smell of embered wood cloyed in my nostrils and I’m not sure if we could really smell the town a thousand feet up or if the sight produced it. And if there were skeletal trees there were human bones. I saw them. Not true skeletons as the connective tissue was gone, but the bones of the dead were everywhere gathered into heaps by some predator and scattered by scavengers. Heaps so big we could see them from here.

Cima vomited. Just the sight of the ruined town. Hurriedly she pushed open the side window and stuck her mouth in the gap and sprayed the glass behind her. This was the city where they did their big shopping, Costco and auto parts, farm equipment. This is where they came for a weekend movie when the one in Delta didn’t interest them. The two towns being almost equidistant from the ranch. She had not seen it end. She and Pops left just as it was getting really bad. When there was still TV news, when the newscasters appeared more exhausted by the day, then scared and exhausted, then terrified as their colleagues dropped away to the hospitals and makeshift flu wards, or were just not heard from, assumed ill or dead, and the last TV anchors stood in, and the field correspondents taped themselves using tripods, the reports more frantic. And were finally cut short by mayhem. I remembered that. Because they had nothing else to do at the end: broadcast, courageous, the way the band played on the deck of the sinking ship, either that or go home and die.

Sometime in there Pops and Cima decided to leave the ranch and they loaded up the gooseneck cattle trailer and towed a little trailer for the four wheeler behind that, and they drove out to the highway in the middle of the night. With a dozen cattle, as many sheep, two saddled horses, two Australian shepherds, and provisions. And Pops had to fight his way through three barricaded ambushes in just the fifteen miles to the creek road, and shoot three crazy fuckers further on in the cedar hills, all of which he was pretty much expecting and didn’t have much problem executing with his guns. But they shot one of the horses and two of the sheep inside the trailer, which made it less easy to pretend the next day that they were driving cows up onto their summer lease as they would on any normal morning in early May. He rode horseback and she drove the ATV, which pulled a small trailer of gear and supplies, the twelve miles into the canyon. She would have preferred to ride, she was never comfortable on four wheelers, but he was skilled at hazing and herding the livestock on horseback and the dogs were, too, and they were used to taking orders from him in the saddle.

The next morning they walked back downstream and he blew the one ford that crossed the creek with dynamite, and made the track impassable except on foot or horseback, and then only at low water.

They swept their tracks as best they could and obliterated them thoroughly for two miles before they left the rough road for the creek trail and the canyon. It took them all day. And then, thank god, two days later it poured rain.

All this she had told me over the last three weeks. So I understood the shock of seeing Grand Junction. It was one thing to lose the whole world as you knew it, another to see, to maybe smell your old neighborhood as charnel house and killing field.

She had made it out the window, streaked the rearward glass, but the plane still reeked. I handed her the water bottle I always kept between the seats and stole a look back at Pops to see if he would be triggered by the smell or the sights below him. It happens that way on boats and planes, the passengers already queasy and one throws up and it’s a chain reaction. But he sat like a Buddha with a lamb in his lap, one strong claw on her shoulder, his face impassive and hard, leaning to the window taking it all in.

Читать дальше