We rode to war in a taxi-cab. Dash found it in Fettlers Lane, near the old greengrocer. We’d gone there looking for food. We were fierce hungry and would have taken anything on offer, but the hostiles had got there first. The place was destroyed. The till was thrown through the front window, the shelves were ripped off the walls. Our feet crunched on glass, and everything reeked of smoke from someone lighting a fire in the back room.

They’d stripped it bare before they’d done the damage – not a tin of beans, not a bottle of water, not a crust of bread. We were scrabbling around in the rubble when Dash yelled and we all charged outside.

The cab was one of those big black hulks – beetles, we called them. This one had a smashed back window, a door torn off, blood spattered across the windscreen and a broken fuel cell: dead, by the looks of it. Bad news for us, because without wheels we were stuck in the city, easy prey for the hostiles. So Dash and Jono had this argument about whether the fuel cell was fixable and I said couldn’t they just try for half an hour and see? And, surprise, Dash stuck her head under the bonnet and fixed it in twenty minutes flat, while Jono muttered and shrugged and the rest of us watched up and down the lane and chewed our fingernails.

When Dash yelled ‘Done!’ we all piled in and took to the road. We didn’t think we were riding to war, of course. Who in their right mind goes to war with an eight-year-old kid in tow? No. We thought we were getting out.

Two weeks earlier…

ISIS came recruiting on Victory Day. Two agents from the Internal Security and Intelligence Services were standing in the shadows at the back of the chapel when we all trooped in for morning prayer. The sun was barely up and we were fasting, but for once we weren’t grumbling. You didn’t grumble when ISIS came to call.

We passed these agents, a man and a woman, on the way in. Tall. Fit. Head to toe in black. And sharp, from their razored hair to their battle boots. Alike as peas in a pod, as bullets in a belt.

We were craning our necks to look at them and whispering to each other, and Dr Stapleton had to rap on the lectern (which meant trouble down the line) to launch us into the city anthem: ‘God bless these ancient city walls and all who dwell herein…’

God hadn’t been doing a great job of it recently, and ISIS had to make up for that. So here they were at school, Tornmoor Academy, recruiting for their labs and their surveillance ops: they wanted smart, so every year they checked out the top senior grades in physics, mathematics, and computing, and in scripture study because they wanted dedicated too. This year we were it, the senior year, ISIS agents-in-waiting.

Dr Stapleton read out the Victory Day message from the General. It was the same message every year: Never forget, never forgive. The invasion of our city will be repelled. The massacre of our people will be avenged. We will not rest until Southside is reclaimed . And the punchline: Remember, always, God Is On Our Side. Victory Is In Sight .

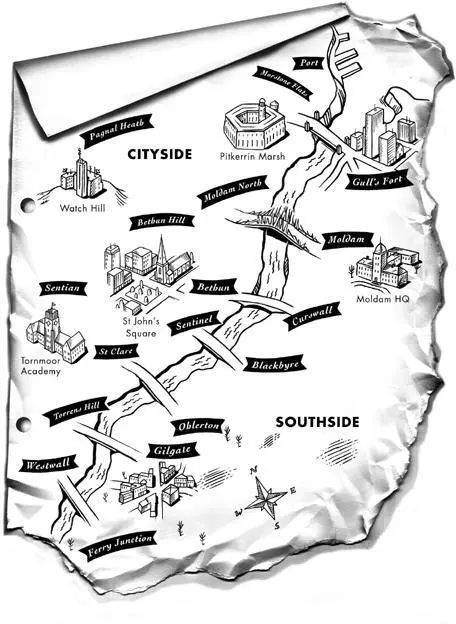

I don’t think anyone actually believed the victory being in sight bit anymore. Not when the latest news upriver was of five brave, stupid church workers who’d ventured over the river into Southside to bring aid or something to the heathens, and who now swung from Westwall Bridge, turning slowly above the water. We’d seen the grainy pictures in the City News . We’d listened to broadcasts of attempts to retrieve the bodies and heard the hail of sniper fire that greeted rescuers every time. Meanwhile, downriver, hostiles had hacked into the flood protection system just in time for a storm surge to meet a high autumn tide and drown Morstone Flats. Hundreds killed, they said. Thousands homeless.

So, no. No one believed that victory was at hand.

Stapleton droned to a halt and Dash was called up to read something from Scripture about battles and bloody vengeance. I wondered what the agents saw when they looked at her. An ideal recruit for sure: tall and sporty, she’d take you on at anything and play hard; blue-black eyes with a seriously sharp brain behind them; thick fair hair clipped close; a way of standing with her neck and shoulders held straight and fine; and this way of lifting her chin when she was on shaky or dearly held ground. Which is what she did as she finished the Scripture reading, as if to say, Go on, disagree – I dare you . But I couldn’t, because I hadn’t heard a word of it.

Dash and I had battled each other for top spot in our year all the way up from junior school. She beat me at applied physics and engineering – she could take anything apart and put it back together better than it was before. I beat her at mathematics and programming. Mostly it was a close-run thing either way. Which meant everyone expected us to be together. And we were. Which was also fine.

We prayed some more. We sang. But mostly we thought about being chosen for ISIS, because that was the prize we’d worked for from day one. Those who missed out would be sent for compulsory service in the army, the factories, or the farms – a grim, boring slog, and long. If you didn’t have family to find you a different job, or claim they needed you at home, you could be stuck for years.

But the chosen ones were in for the ride of their lives. ISIS was the brains behind the war. Its agents worked in hi-tech, often high-risk, operations in surveillance, cryptography, and forensics dedicated to outwitting and defeating the hostiles. What better way to avenge the people we were now about to honor.

The thirty students chosen this year to commemorate their murdered loved ones were stepping forward under Stapleton’s ferrety eye. Everyone was on extreme best behavior now, standing straight and serious and repeating the response after each name: We will remember them. God bless the city . In twelve years at Tornmoor I’d never once been up there to speak my parents’ names. They’d been killed in a bomb blast when I was a little kid. Not being chosen year after year didn’t bother me, and, to be honest, I didn’t remember their first names, exactly, which was why, maybe, I’d never been chosen. But Stais, Mr and Mrs , that would have been okay.

We filed out of the chapel’s dark, ancient spaces into the bright auditorium where Dr Gorton was practically having a seizure trying to get us organized. He scurried up and down the stairs beside our rows, muttering and gibbering, ‘Are we ready? Are We Ready?’ He stopped beside Lou, who’d unwisely picked an aisle seat. ‘Hendry! Is that gum? You are chewing gum. Few are called, Hendry. Fewer are chosen. You will never be one of them. Get Rid Of It.’ Slap, slap, slap on the back of Lou’s pricey haircut. Lou ducked, winked at me, and grinned. He had no intention of being chosen for anything other than an easy life in the soft bed of family trust funds and parental doting. But I was a scholarship kid. A few brain cells were all that lay between two futures for me: working with the most brilliant minds around to win the war, and being sent upriver to batter hostiles into submission with a life expectancy I wouldn’t like to speculate about. This was my chance. I intended to grab it.

Читать дальше