“Again! Again!” he shouted, like a demented Tellytubby.

The vehicle rocked from side to side in the winds, making me feel seasick.

Dad unbuckled himself and tried to stand. His legs went from under him, though, and he fell forwards on to the console. “Woah, dizzy,” he gasped.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Need to see where we’re coming down,” he wheezed in reply, then he staggered back into the belly of the vehicle, bracing himself against the walls as it swayed.

“Are you mad?” I asked, unbuckling myself and tumbling after him. “You don’t know how high we are, whether we’re even in breathable air yet. If you go too soon, we’ll depressurise. If you go too late, you could be unbuckled when we hit the ground and that would not be good.” I grabbed his arm and held him back.

“Lee, we might not even be over land.”

“Shit,” said Tariq, who hadn’t bothered to unstrap himself, and was still lying there. “You mean…”

Dad nodded. “We could hit water and sink like a stone. We could be over the Med or the Channel, I don’t know. Or maybe over a mountain range. For all we know, we could hit the top of a snow ridge and tumble all the way down the bloody Eiger.”

“And what would we do if we were coming down over the sea or somewhere worse?” I asked. “What good would knowing do us? I doubt this thing has a life raft, or skis. Does it have retractable skis?”

Dad glared at me and then smiled in spite of himself. “No, no skis.”

“Shocking lack of foresight, that.” Dad held my gaze as I shrugged and said: “All we can do is strap ourselves back in and hope. I didn’t come rescue you so you could take a nose dive out of an armoured vehicle at 20,000 feet.”

He paused and then nodded. “When did you become the grown-up?” he asked as we strapped ourselves back in.

“Ask Mom,” I replied and then instantly wished I hadn’t. I avoided his eyes and didn’t say another thing.

“All right,” said Dad a few minutes later. “We’ve got lots of parachutes holding us up, and the pallet we’re on is slightly cushioned, but it’ll still be a hell of a jolt when we land. So be ready.” We sat, rocking gently, listening to the wind whistle by outside, feeling the hollowness in our stomachs as we fell.

“Do you reckon…” began Tariq, but he was interrupted.

We hit something but we didn’t stop falling. The vehicle spun 180 degrees around its centre axis until we were upside down. Then there was another crash and we spun the other way, facing nose down, still falling. Loud cracks and bangs echoed through the metal structure as we fell, swivelling and spinning wildly.

“Trees!” shouted Dad.

Our stop-start, rollercoaster descent slowed as we crashed down through branches and bowers until finally we came to a halt, swinging, facing downwards at 45 degrees. We all caught our breath. The only sound was the creak of wood from outside.

“Everyone okay?” asked Dad.

Tariq groaned and lifted a thumb. I tried to nod, but my neck hurt in all sorts of interesting new ways. “Yeah,” I said. “Nothing two years of intensive physiotherapy wouldn’t fix.”

“Good.” Dad breathed out heavily. “Fuck me, that was a bit drastic wasn’t it? Remind me never to do anything like that again. And next time, son, bring a bloody gazunder. Anyway, we’re stuck. Which is good.”

“Huh?”

“If we’d just hit the ground cold, it would have been the equivalent of falling twelve feet. In a chair. We’d have been lucky not to break our backs.”

“Now you tell us,” groaned Tariq.

Dad activated the driver’s side periscope, but the view was obscured by parachute silk, so he unbuckled himself and clambered down the cabin to the gunner’s periscope, which was also blocked. He climbed to the hatch, pulling his knife from its sheath as he did so.

“You both stay here, buckled up. I’ll go see what state we’re in.”

The vehicle swung perilously as he moved around in it, making me feel seasick. He opened the hatch and shoved aside a swathe of silk.

“We’re in a forest,” he said. “Pitch black, no lights, could be anywhere.”

He climbed outside and we could hear him scuttling around on the shell of the vehicle. “We’re only about six feet off the ground and we seem pretty well braced. I think you should unbuckle and jump down.”

Tariq and I unstrapped ourselves, climbed to the edge of the roof and jumped on to a soft bed of pine needles. Dad stayed on the vehicle.

“Get clear,” he shouted. “I’m going to cut some of the parachute straps and see if I can get this thing on the ground the right way up.”

“Don’t be daft,” I replied. “If you cut the wrong cord, the Stryker could flip and land on you.”

“Just get clear, Lee,” he said impatiently.

I knew that tone meant no arguments, so I walked away and watched, nervous as hell, as Dad sawed away at the various parachute cords that were holding the vehicle in a complex swaying web. Each cord gave way with a loud twang, huge amounts of tension being released as they snapped. The vehicle lurched, first one way, then the other, then forwards, then backwards. It was like Dad was playing some vast, lethal game of Kerplunk. Cut the wrong cord and it was all over.

Bit by bit the vehicle came free, swinging more wildly as it hung by fewer threads. Then Dad made a mistake, cut the wrong cord and the whole thing pivoted and pointed nose down. Dad was flung forward and was left hanging off the gun turret. Tariq and I gasped, but Dad pulled himself up the roof until he reached the rear bumper. Reaching up with his knife, he cut the last cord and the vehicle dropped on to its nose. Then it slowly toppled backwards and landed the right way up, flinging Dad off it like a bronco rider on a bad day. He landed in a heap, but he was fine.

He stood up, brushing the dirt and pine needles off him. “Right,” he said, “let’s get this show on the road!”

We cut the straps that bound the vehicle into the pallet, and disconnected the final straggling parachute cords. Then we climbed inside and Dad booted her up. Even after that insane descent, she started first time. The touchscreens came to life. Dad pored over them for a minute or two and then announced: “It’s Bavaria.”

“What?” I said, incredulous.

Dad turned around, facing Tariq and me with a big smile on his face.

“It’s Bavaria. We’re just outside Ingolstadt.”

“How the hell do you know that?” I asked.

“The satnav’s working!” he replied with a grin. “All right, what’s your postcode?”

THE STRYKER WAS designed for road clearance, and Dad drove like a demon, so we made good time. Germany’s autobahns and France’s highways proved impassable, but the satnav steered us down side roads and country lanes, always heading for our next stop — Calais station and the Channel Tunnel.

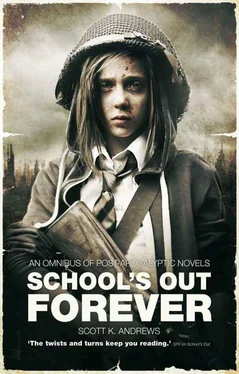

A couple of times we encountered roadblocks manned by gangs of marauders, but we kept driving straight through them as the bullets pinged harmlessly off our carapace. I knew that the Americans would have attacked England by now, and the knot of fear and anticipation in my stomach wound tighter with every mile. What would I find when we got to the school? Would it be a smoking wreck, ringed by the impaled corpses of my friends? And if so, how could I ever live with myself? I grew quiet and sullen, eaten up with stress, so it fell to Tariq to pepper our journey with anecdotes and nonsense. Sometimes he managed to get a smile out of me, but not often.

Dad and I didn’t talk much, but the silence was less charged than it had been in Iraq. Perhaps he was starting to accept that I was more man than boy now, whatever my age. Or perhaps I was just enjoying being with him, watching him be heroic and confident, enjoying having someone look after me for a change, instead of me bearing all the weight. Either way, it was better. Not right, but at least better.

Читать дальше