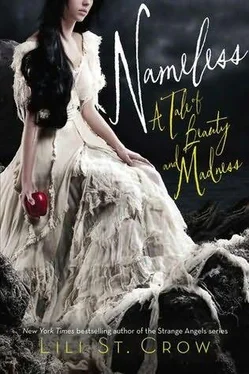

Nameless

(The first book in the Tale of Beauty and Madness series)

A novel by Lili St. Crow

For all of us.

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PROLOGUE

PART I: A Princess

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

PART II: Waking Up

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

PART III: The Sacrifice

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

OF ALL THE CARS IN NEW HAVEN TO FALL BEFORE, I chose Enrico Vultusino’s long black limousine.

The Dead Harvest had been dry for once, but Mithrus Eve had brought a cargo of snow, a white Mithrusmas for New Haven after all. There was the alley, close and dark and foul. The reason that I ran, I know, was a rat with a loathsome plated tail and beady little eyes. For years I remembered nothing before the rat, which was probably a mercy.

Fierce fiery cold, and the car’s tires squeaking as they crushed the swiftly-thickening carpet of white. The headlamps made everything a blare of blank cold brilliance, like the light dying people are supposed to see at the end of a stone tunnel. The brakes were grabby that night—I’ve been told the story so many times I can repeat it almost word for word.

If you don’t mind waiting while my tongue stumbles over it, I guess.

Chauncey was driving Papa Vultusino home from the traditional Seven and Elders meeting, watching the snow clot the wipers on the bulletproof windshield, thinking of nothing more than staying on the road and getting everyone home safe. He saw a flicker; the instinct of two decades of driving in New Haven rose under his skin and he jammed on the brakes, hoping the tire treads were deep and the snow thin enough to give him some traction. The limo slewed sideways and the small shape toppled, lay curled in a ball under an awkward slice of headlamp glow.

There was a splash—Vultusino had dropped a glass of whiskey and calf. Thankfully, it hadn’t broken. “Chauncey?” His voice floated from the backseat through the open pane of more bulletproof glass, down because Chauncey liked the smell of Papa’s cigars.

Chauncey blinked, restrained the urge to rub his eyes like a waking dreamer. “There’s a kid in the road. Not smoking, so it’s not a faust. Doesn’t look like a Twist either.”

Another sound—a click. Trigger Vane, sitting next to his employer, had pulled a nine-millimeter Stryker from its holster. His other hand touched the hilt of a wood-bladed dagger—good against fausts and some Twists, but not against minotaurs.

Nothing but running is good against minotaurs. And even that may not work.

Taut and ready, Trig’s chin tilted up. “Sir?”

Papa’s salt-and-pepper mane nodded. “Take a look.”

So it was Trigger, his lean lanky frame in a violently plaid, orange-yellow sportcoat and baggy chinos, the gun in his hand, who bore down on me, each step squeak-crunching in the snow. He glanced around—it wasn’t unheard of for an ambush to happen, even on such a hallowed day as this—but saw nothing. He stood for a few moments, gazing down on a child, her hair a messy tangle of deep blackness.

She appeared fully human. So thin bones were working out of her pallid skin, and she shivered like a trapped rabbit. Bright red striped her trembling legs, wasted muscles twitching as if she thought she was still running.

Around him, the town remained Mithrus Eve silent, snow whirling down. This was the industrial section, slumping buildings full of heavy machinery and poverty, slaughterhouses, Twisthouses, and desperation. A train newly arrived from the Waste chugged in the distance, its lonely whistle struggling through the deadness of falling flakes.

And somewhere, there were dogs, muffled as they bayed with frantic excitement.

It was the child’s bare feet, filthy and bleeding, that convinced Trigger this was no decoy, no ambush. Not many would attack the Family, and their internecine rivalries were not redhot-smoking as they had been in some other years. All was calm, the Seven were in accord, and New Haven was tranquil enough.

He stood, stolid, for what seemed a long time. Thinking quickly wasn’t Trig’s strong suit unless there were bullets involved, or violence. He preferred to chew anything else over thoroughly before he made up his mind.

The child wore a thin faded-white cotton dress far too small for her; her legs were covered with welts and burns, fresh slices welling with hot blood. She was so bruised and thin, he often remarked, that he wondered if she’d just dropped dead in the road. But her breath made a small frosty cloud over her face. Panting lightly, and likely to be dead of cold or shock before long.

He paced back to the car. “It’s human,” he murmured through the back window, dropping the words into Papa Vultusino’s waiting silence. “Barefoot. Beat up pretty bad.” He paused. “A little girl.”

Papa blinked. What he was thinking in that moment nobody has ever ventured to explain or guess. “Bring.” His accent, the ghost of another language that haunts Family wherever they settle, thickened the word.

So Trigger returned to the little girl in the snow. He bent to pick her up, and she nestled limp in his arms. He carried her to the limousine and managed to fold himself up inside the warmth of the car. His large capable hands could have held the girl still if she’d struggled, but she didn’t.

They might have taken me to the hospital immediately; a police report could have been filed. But none of them liked the police, though the Seven owned the law in New Haven. The Family remembers other countries where the police were the enemy; they don’t ever forget an enemy.

That’s one thing “Family” means.

Papa Vultusino examined the shivering little girl, who stared wildly, blank-faced and trembling. Eyes as blue as her hair was black, and her skin so cold and oddly translucent, as if she had never seen the sun. The wounds on her legs were vicious, some of them still seeping thin crimson and others oozing.

Even that trace of red was dangerous. Another of the Family might have wanted it, fresh and hot even if its vessel was weak and perhaps infected.

But Enrico Vultusino did not Borrow from children. Not like some of the Stregare, whose favorite vessels are those smallest and most fragile. No, he was the Vultusino, the head of a proud Family, and weak prey did not interest him.

Or perhaps it was something else, moving through his old, canny, labyrinthine brain.

Finally, Papa stirred. “What’s your name, little girl?”

I remember leather and spilled liquor and copper, whiskey-calf if the story is told correctly. For almost as long as I can remember that has been the aroma of safety for me. That, and Papa’s bay-rum aftershave, as he peered at me through his wire-rim reading glasses. “Little girl, piccola, what is your name?”

I began to cry. Why isn’t exactly clear to me, unless it was the stinging of heat in my hands and feet and the throb of cuts and welts returning to shivering life. Big tears splashed on my refuse-caked dress, but I made no sound. I had learned to cry quietly, wherever I’d been, and years later someone told me that Papa Vultusino’s mortal wife had wept like that before she died, tears and silence and nothing else.

Читать дальше