“Let me guess, the local guard was murdered in a horrible way.”

“Probably,” Derek said. “The body is missing but there was a lot of blood. Hibla wants to know what’s going on.”

Doolittle picked a pipette and dipped it into the Wolf test tube. “The essence of the test is based on the assimilation properties of Lyc-V. When faced with new DNA, it seeks to incorporate it.”

He uncorked the Bear test tube and let two drops from the pipette fall inside. The blood turned black, swirled, and dissolved.

“Assimilated,” I guessed. The Lyc-V had chomped on the foreign DNA.

“Precisely.” Doolittle picked up a test tube marked Bear II. “The blood in this test tube is from Georgetta, but the blood in front of you is from her father.”

He sucked a couple of drops from George’s test tube and let them fall into Mahon’s blood. Nothing happened.

“Same species.”

“But wouldn’t the difference in human DNA affect it?”

“It does, but you won’t see a dramatic reaction.” Doolittle leaned forward. “We’ve tested the blood from the man you killed against all of these. Every single one gave a reaction.”

“Even the lynx and lion?”

Doolittle nodded. “Whatever it is, it may look feline, but it’s not. If it is, its DNA is significantly different from that of a lynx or a lion.”

“So where do we go from here?”

“We try to get more samples,” Doolittle said.

That would be problematic, to say the least. I tried imagining walking over to the Volkodavi or Belve Ravennati and telling them, “Hi, we suspect that one of your people might be a terrible monster; can we have your blood?”

Yeah. They would just fall over themselves to donate a sample.

“I could pick a fight,” Derek said. “Get some blood that way.”

“No fights. We start nothing. We only react.”

“That’s exactly what I said.” Doolittle fixed Derek with his stare. “Also, Kate, if you do run across another specimen, do try to keep him or her alive until I get there.”

Ha-ha. “Will do, Doc. My turn.” I opened the Bible and showed him the verse from Daniel.

Doolittle read it, raised his glasses onto his forehead, and read it again. “I’ve read the Bible hundreds of times. I don’t remember reading this.”

“You weren’t looking for it.”

Derek came over and read the verse.

I brought them up on Daniel’s brief history. “The beasts in Daniel’s dream are usually interpreted to mean kingdoms, in this case Babylon, that will eventually fall from glory. But if taken literally, it could mean a shapeshifter.”

“Were there winged cats in Babylon?” Doolittle asked.

“The only thing close were the lamassu,” I told him. “Lamassu served as the guardians of ancient Assyria. Assyria spanned four modern countries: southern Turkey, western Iran, and the north of Iraq and Syria. Assyrians liked to do war, and they fought with Babylon, Egypt, and pretty much everyone they could reasonably conquer in ancient Mesopotamia for about two thousand years. Around six hundred BC, Babylonians, Cimmerians, and Scyths, all the nations who had once paid Assyria tribute, finally banded together and sacked it. We don’t have many records of the Assyrians. They left behind some ruined cities and stone reliefs depicting fun things like impaling entire villages of subjugated people and riding around in chariots hunting lions.”

“Amusing people, the ancient Assyrians,” Derek said. “They hunt, they sing, they dance, they impale people.”

A joke. Finally. “Pretty much. They also built lamassu, massive stone statues that guarded the city gates and the entrances to Assyrian palaces.”

I opened the Almanac and showed them the picture of the colossal statues. “Bearded human face, body of a lion or a bull, and wings.”

“Why five legs?” Doolittle asked.

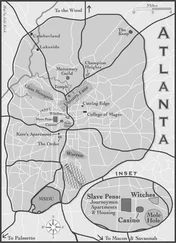

“It’s conceptual: from the front the lamassu seem to be standing still, but from the side they appear to walk. Here is an interesting thing: Assyria wasn’t that far from here, about a thousand miles southwest as the crow flies. It’s a thousand miles of mountains and terrible roads, but in country terms, ancient Assyria and ancient Colchis were practically neighbors.”

Derek frowned at the picture.

“But they have human faces,” Eduardo said. “And no scales.”

I nodded. “And that’s a problem. Also there are dozens of theories as to who or what the lamassu represent, but not one of them says they were evil or that they ate people. They are viewed as benevolent guardians. People have found amulets with lamassu and protective spells on them, and modern Assyrians still have their images in their houses.”

Doolittle studied the picture. “To show a creature with five legs demonstrates understanding rather than observation.”

“What do you mean, understanding?”

“They didn’t simply follow nature’s blueprint and make exactly what they observed,” Doolittle said. “They understood the difference between perception and reality, and they portrayed a concept rather than the exact copy of what they could see.”

Doolittle took a piece of paper and a pen and began to draw. “When we are born, we start out with concrete thinking. We perceive only what we see and hear.” He showed us the piece of paper. On it a dove soared above a crushed birdcage.

“What do you see?”

“A bird flying away from a broken cage,” Derek said.

“What does it symbolize?”

“Freedom,” I said.

“What else?”

“Escape,” Eduardo said.

Doolittle turned to Derek.

“Leaving what is safe so you can be more,” Derek said. “The cage is what the bird knows; the sky is all the things he still wants to do, even if it’s a risk.”

“Ah!” Doolittle raised his index finger. “All those are examples of abstract thinking. Our entire culture is based on the idea that a single concept can have many different interpretations. We actively encourage the development of this skill, because it helps us solve our problems in new ways. So did the ancient Assyrians, apparently. When looking at the lamassu, we have to consider not only what it is but what it may represent. We can’t simply take it at face value.”

The million-dollar question was, what could a scaled bull with a human face and wings symbolize?

A knock sounded and Andrea and Raphael came into the room. Keira stalked in behind them and winked at Eduardo.

“Stop that,” Eduardo told her.

I leaned over to Doolittle. “What do you think it represents?”

“Let me think about it,” he said.

Barabas was the last to arrive. We were missing Curran and Mahon, and Aunt B and George, who were guarding Desandra. It would have to do.

“Desandra doesn’t do well with men,” I said. “We need to have a woman with her at all times. I’m thinking three shifts, two people per shift. Midnight to eight, eight to four, and four to midnight. Volunteers?”

Raphael raised his hand. “We’ll take eight to four.”

“I can take four to midnight,” I said. “I need a partner.”

Derek raised his hand. Perfect.

“I’ll take midnight to eight,” Keira said. “I don’t mind sleeping in the room and I talked to George last night. We’ll work well together.”

“What about me?” Eduardo asked.

“You and our good doctor are joined at the hip for the rest of our stay here,” I said. “I have a feeling that Curran will be busy.”

“He will be,” Barabas confirmed. “I have several requests for meetings with him. He’s an arbiter, so the packs will likely want him there any time they decide to talk.”

“That leaves us with you, Mahon, and Aunt B,” I said. “I’ll talk to both of them and see if they would mind acting as standbys in case we need extra support: twelve hours on, twelve hours off. Same instructions as last night until further notice: we do not go anywhere alone, we do not take risks, and above all we do not permit ourselves to be provoked. One last thing: the most dangerous person in this castle isn’t Jarek Kral or any of the other pack alphas. It’s Megobari.”

Читать дальше