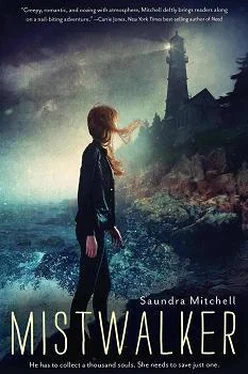

When the fishing was good, Daddy sometimes got on the radio and sang. Just a verse or two—a dirty song about ruffles and tuffles sometimes. Chanteys sometimes. But usually this song. “She Moved Through the Fair,” slow and haunting and dark.

Shining with a light I’d never seen before, Grey smiled when the song wound down. The last note plucked, and he offered me the box. “I wished for something to make sense of you, and this is what I got. It’s a message.”

“You know that song, Grey?”

“I’ve heard it many times.”

“Yeah, but do you know it?” I asked.

The expression drained from his face. “Do you?”

Fear crept through me because I knew something Grey didn’t. I knew all the words; I’d heard the song a hundred times. Uneasy, I glanced back to make sure the dory waited for me at the shore.

Then, I turned to him and said, “She never comes back, Grey. He sees her once at the fair and spends the rest of his life missing her.”

If it was possible, Grey paled. Closing the box in his hand, he stiffened. “She whispers in his dreams.”

“It’s all in his head.” Though my heart pounded, I went on. “Whatever magic that works here, whatever gave you that music box? It wasn’t wrong. Because I’m not your escape.”

He broke. I saw it in his eyes. In the trembling of his hands. It was like he’d been sleeping two sleeps, one of curses and one of fantasies. I’d just shattered the only beautiful one for him.

When he said nothing, I moved toward the path. Still he said nothing, and panic bloomed in me. Until now, he’d never been at a loss for words. If some terrible, devil version of him existed, I didn’t want to see it.

When my feet hit the path, he screamed. A plaintive wail, one that echoed longer than it had lasted. Then he called after me.

“Don’t go! I’m alone. I’m going mad; it’ll take thousands of years to collect enough souls to get off this island!”

It felt like he’d thrown a spear. Like I’d been split and pinned by it. My chest hurt, and my head, too. I knew there had to be something else. There had to be something he’d been sugarcoating. “Souls?”

“I’m not a monster,” he raged. “I could have smothered your village’s fleet a hundred times by now . Lost them all at sea, collected every soul at once, and I never have! I’ve been a boon to Broken Tooth. I’ve kept you all safe! Kept you safe in particular, Willa. The night you and your brother went into the dark, I tried to protect you. To hide you!”

“What do you mean?”

“Come with me,” he said. He held out a hand. It was pale, and in the moonlight, it looked skeletal. Suddenly, he was a long, gangling thing. Bones and angles, and it made my skin crawl. But I followed him, because I had to know. Because he had something inside his head, and it had to do with me, and Levi, and I had to know.

It wasn’t the music-box room when we went through the door of the lighthouse this time. Not the kitchen, either, or any of the rooms I’d seen. It looked like a pantry, sort of. Wood doors lined the walls. A bitter smell wafted on the air, like old paper, or an unused closet. Grey opened one of the doors.

Row after row of glass bottles lined the inside. Each hung in its own nook. Corked, they were empty. And they didn’t make sense. The jars weren’t much bigger than my thumb. They didn’t look like test tubes or like they were for spices. Light reflected on their rounded bottoms. I tightened my arms around myself because a chill came on.

“I could have collected you the night of the storm,” Grey said. “I risked myself. I tore myself to shreds to get to you, to save you! I am not a monster.”

The jars tink ed, shaking in their neat slots. It was like they were alive. Or something bigger than all of us was subtly shaking the lighthouse. My heart decided to quiver too. I felt sick and uneasy, but all I could do was ask questions.

“How’s that, Grey? It doesn’t even make sense.”

Closing one door, Grey opened another. Tilting his head to the side, like he was admiring art, he considered the three uppermost jars. They glowed, like each one had a firefly caught inside. When I stepped closer, Grey pressed himself between me and his precious jars.

“There are two ways off this island. The first? Collect a thousand souls. Anyone who dies on the water, beneath my light . . . a tally in my book. This is a century’s worth.”

All my blood drained away. I felt raw and cored, and I wanted to fall to my knees. If this was the truth, if any of it was real . . . My head split; it felt like Grey had dropped an axe instead of some words. Too many questions. Too many possibilities.

My hand shaking, I pointed. “What is that?”

“All that remains.”

I lunged past him, trying to grab the bottle. It was like hitting a wall. Icy, immovable. When I lunged again, the pantry shifted. It was there, then I took a breath, and it was gone. All that was left was music boxes. All of them, keys ticking. Notes playing. Each one played a different song, none of them in tune. In time.

Throwing myself at Grey, I grabbed his shirt. I shook him. “You let my brother die!”

“No, Willa,” he said, newly, coldly calm. “You killed your brother. I only kept what was mine.”

I tasted bile, but I wasn’t gonna turn myself inside out for Grey. For that thing. For all I knew, it was a hallucination. Another lie. There was nothing left of Levi. He was dead and gone. Gone.

Shells and stones ground beneath my feet, because I walked away. I ran. Putting my back to him, to that lighthouse, I dared him to do something about it. I wasn’t gonna be a part of this. Everything on the Rock would become myth again for me, I hoped forever.

“I promised to be honest with you, Willa! You can’t hold the truth against me. Your brother was one more toward a thousand, it’s true! But he was a happy accident. One I tried to prevent, one you engineered!”

Biting my own lips, I held in a reply. I held in everything: my gaze, my voice, my churning belly. If I could have made it a mile in icy water, I would have swum home instead of getting into that cursed boat.

Instead, I sat at the bow, staring into the sea. Staring at the shore. Looking everywhere but behind me.

I was never going back to Jackson’s Rock, not even with my eyes.

When the Big Dipper is upside down, it will rain for three days.

My father believed that—he, long dead now. My mother didn’t; she, too, molders in the earth. Every home I ever knew is ashes. Every street I ever walked, paved over. No one I knew by name, who could greet me with mine, remains aboveground.

The stars are all turned, and it hasn’t stopped raining since Willa left. Cold, ice rain that makes me glad I only imagine my body. I think I save myself from the worst of mundane realities. I feel cold, but I don’t go numb with it. I feel heat, but I never sweat.

Because I’m dead. A remnant. A revenant.

She’s not thinking of me.

I’ll never be free.

Every time I started to look toward the Rock, I distracted myself. It was hard, because the weather went crazy. Well, not the weather so much. The fog.

It rolled in and out, wildly random. The horn blared constantly, sometimes for ten minutes, sometimes for four hours. It was like a strobe light in slow motion. White, then clear. Clear, then white.

But distraction didn’t come too hard. The way my parents saw it, I’d disappeared for three days after court. Long enough that they reported me missing. Long enough that a patrol car came to our house when I turned up.

Читать дальше