Gillian Anderson and Jeff Rovin

A VISION OF FIRE

Rocking gently under the full moon, the Falkland Advanced Petroleum survey ship rested in the harbor at Stanley. Its hull was weather-beaten after three weeks at sea, its sensitive below-deck sensors were rattled by the relentless waves, and its chief geologist was exhausted.

But as he bent over the tiny lab table in his forward cabin, Dr. Sam Story could not stop staring at a rock the remote-controlled Deep Sea Grab Vehicle had pulled from a ledge on their last day in the South Atlantic. The silvery stone fit in his palm and was roughly the shape and thickness of a playing card. He had been studying it for more than an hour through a magnifying glass, slowly moving the lens up and down and side to side; the fifty-three-year-old geologist was finding it difficult to accept what he was seeing.

Finally, the man sat upright on the stool, blinked his tired eyes, and thumbed on a small audio recorder.

“Specimen E–thirty-three,” he intoned cautiously, “definitely appears to be a pallasite meteor fragment. And it is my observation that chipping marks on the back indicate it was hewn from the parent stone by hand. However…”

He gently set the stone on a cotton swath he’d placed on the table and pulled off his latex gloves. The relic had been washed by frigid waters for centuries, perhaps millennia, and rough surfaces and body oils might cause further damage.

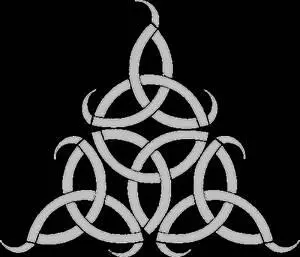

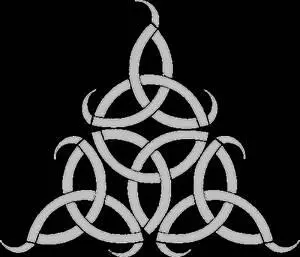

Dr. Story looked down at the stone again and studied the symbol that gently shone from it. “On the anterior façade is a carving of four triangular shapes arranged in a pyramid,” he recorded. “Each triangle is formed by three interlocking crescents, with small, extended crescents at the three corners. More of a claw or talon shape, actually, those small ones. No claws at the corners of the center triangle. I cannot begin to guess at the meaning or function of this.”

He bent low, peering at the stone. “Regarding process, the width and depth of the markings suggest they were carved by a smaller, finer tool than that which made the relic itself. While there existed any number of local tribes that could have cut these figures, the edges of the markings themselves are a real mystery.”

Picking up the magnifying glass again, he murmured, “Every side of every etching has a rounded perimeter that suggests eons of erosion. Yet these edges are not worn down uniformly but are built up, like blisters. Blisters like these could only be generated by intense heat, Class D at a minimum, and ancient peoples did not have the wherewithal to generate twenty-one hundred degrees Fahrenheit.”

Dr. Story sat upright, picked up the recorder, and grinned. The modern device felt strange and inconsequential in his hand. This relatively sophisticated by-product of human invention was dramatically less interesting than a simple stone pulled by chance from the ocean.

No , he corrected himself, this is not simple . Volcanic magma could reach that level of heat, but even that was uncommon. By the time lava reached the surface, it was closer to fifteen hundred degrees Fahrenheit. He had only seen this kind of melting and hardening on meteoric rocks that softened and bubbled during their flaming passage through the atmosphere and hardened when they reached the cooler surface, free of friction.

“But that doesn’t explain how the carvings melted,” he mumbled into the recorder. “ They couldn’t have come through the atmosphere. That would mean they had to originate in…”

Dr. Story was tired. He had been awake for nearly forty-eight hours. Before he considered the implications that the evidence suggested, he needed rest.

Turning off the desk lamp, he fell into the small bed that folded down from the wall. The gentle rocking in the harbor was a balm after twenty-one days at sea. Despite a sudden thumping on the hull beneath the water—possibly a pilot whale; the cetaceans had shown a surprising tendency to beach themselves of late—the scientist was asleep within moments.

The door opened and a figure entered the room. He moved quietly, cautiously. The rocking of the boat was unpredictable and he did not want to fall against the desk or the bed.

The man laid an empty camera case on the floor. Guided by the light of the moon through a porthole, he quickly gathered up the tablet and the audio recorder. He swaddled the small piece of rock in its cotton wrap and placed it in the camera case.

And then he was gone, headed away from the public jetty. Dropping the two electronic devices into the water, he watched their gurgling descent in the ivory moonlight, then continued toward the Malvina House Hotel.

PART ONE

It was an unseasonably warm October morning, better suited for a stroll than a stride, but Ganak Pawar and his daughter maintained their usual quick pace up the east side of Manhattan. The permanent representative of India to the United Nations, veteran of thirty years as a foreign-service officer, wore a practiced expression of tolerance. Sixteen-year-old Maanik seemed especially energized by the blanket of sunlight that spilled across York Avenue.

“Papa, your presentation last night was amazing!” Maanik said. “I couldn’t get to sleep for hours, my brain was alive with so many ideas.”

“That is gratifying,” her father replied.

“It’s time for people to think differently about Kashmir and you made that point with the General Assembly,” she said. “I’m glad CNN covered it, it was totally inspiring.”

“I am glad you feel so. I am not being universally thanked for it.”

“Papa, you got in their faces. That took courage!”

Ganak smiled. “I ‘got in their faces,’ did I?”

“You know what I mean,” his daughter said, grinning. “Anyway, don’t be so modest, especially now. Now is the time for a determined follow-up.”

Ganak wasn’t sure if it was courage or desperation that had compelled him to show the video of a Kashmiri mother immolating herself over her dead son. Tensions occurred in Kashmir every few years but this time it felt different. Thirty-two people had died in two days, and Pakistan and India were once again rattling their nuclear sabers. Perhaps that familiar, tired bragging had driven Ganak to suggest they make Kashmir a UN protectorate. If the UN temporarily governed the region, as it had in Kosovo for nine years, that could buy time for the populace to choose whether to join one country or the other, or to opt for independence…

“Papa?”

“Yes?”

“I want to be part of that follow-up,” Maanik said, bouncing in her stride with excitement. “You should hear my ideas.”

He smiled as he regarded her. She looked so mature in her brown faux leather jacket over a dark blue dress. Her leggings were orange and gold, one leg striped horizontally, the other swirling in a feather pattern. She had sewn the disparate halves together herself and matched them with an orange and gold scarf. He noticed with surprise that she had begun to pluck her eyebrows, and though her black hair had always been strong and thick, the way she arranged it over her shoulder was a recent development.

She is so unlike her mother , he thought. When the Pawar family had moved from New Delhi to Manhattan two years ago and Maanik started at Eleanor Roosevelt High School, the girl immediately began to change. Where her mother, Hansa, was reflective, Maanik did her thinking aloud. Where Hansa planned, Maanik improvised. Hansa embraced tradition but Maanik liked to Rollerblade on the sly with the son of the Canadian ambassador. The Pawars’ American bodyguard, Daniel—who was walking a few paces behind them—was charged with clandestinely keeping an eye on the young lady when she was not at home.

Читать дальше