Blomqvist thought a freighter crew made up of closely related individuals, especially when marriage was involved, was a subject of derision and wonder. He'd learn, soon enough. A high percentage of the crews of such freighters—"gypsies," they were called, usually small in size and with no regular runs of any kind—were comprised of people related to each other. There were whole clans and tribes out there, working the fringes of the interstellar freight trade. Some of them were so large they even held periodic conclaves; where, among other things, marriages were contracted. There were some powerful incentives to keeping their businesses tightly held, after all.

Unlike her new partner, whom she'd already decided was a jackass, E.D. was not given to much in the way of prejudice—at least, so long as genetic slaves weren't involved. On that subject, she had the same attitudes as almost all freeborn Mesans.

But, unlike Blomqvist, who, despite the benefits of a good education, seemed remarkably incurious about the universe into which he'd been born, E.D. hadactually absorbed what she'd learned as a student in one of Mesa's excellent colleges. Those colleges and universities, of course, were exclusively reserved for freeborn citizens. Mesa didn't forbid slaves to get an education, as many slave societies had done in past. They couldn't, given that even slaves in a modern work force needed to have an education. But the training given slaves was tightly restricted to whatever it was felt they needed to know.

She'd been particularly fond of ancient history, even if the subject had no relevance to her eventual employment.

"Why should tramp freighter crews sneer at the same practices that stood the dynasties of Europe in good stead?" she asked. "To this day, I think the Rothschilds still set the standard, when it comes to inbreeding."

Blomqvist frowned. "Who's Europe? And I thought the name of that dog breed was Rotweiler."

"Never mind, Gansükh." She leaned over him, studying the screen. "Cargo . . . nothing unusual. Freight brokerage . . . okay, nothing odd there."

Blomqvist made a face. "I thought Pyramid Shipping Services was one of those outfits serving the seccy trade."

"It is. And your point being . . . ?"

He said nothing, but the sour look on his face remained. Normally, Trimm would have let it go. But she really was getting tired of Blomqvist's attitudes—and, looked at the right way, you could even argue she was just doing her job by straightening out the slob. Technically, she was Blomqvist's "senior partner," but in the real world she was his superior. And if he didn't realize that, he'd soon be getting a rude education.

"And what would you prefer?" she demanded. "That we insist the sutler trade be serviced by the Jessyk Combine? No—better yet! Maybe we should have Kwiatkowski & Adeyeme handle it."

Blomqvist grimaced. Kwiatkowski & Adeyeme Galactic Freight, one of the biggest shipping corporations operating out of Mesa, was notorious among System Guard officers for being a royal pain in the ass to deal with. Worse than Jessyk, even though they didn't have nearly as much influence with the General Board.

Still, they had enough. The quip among experienced customs agents was that any finding of an irregularity by a K&A freighter guaranteed at least fifteen hours of hearings—and, if people had still been using paper, the slaughter of a medium-sized forest. As it was, untold trillions of electrons would soon be subject to terminal ennui.

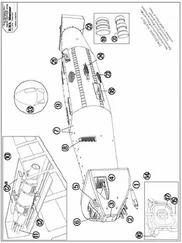

She straightened up. "Just take my word for it. Everyone's better off leaving the ragtag and bobtail seccy trade to the gypsies. Easier for everybody, especially us. The only important thing—check this for me too, if you would—is how long the Hali Sowle is requesting orbit space."

Blomqvist pulled up yet another screen. "Anywhere up to sixteen T-days, it looks like."

Trimm frowned. That was a littleunusual. Not unheard of, by any means, but still out of the ordinary. Most gypsies wanted to be in and out of Mesan orbit as fast as possible. Not because the Mesan trade gave them any moral qualms, but simply because they weren't making money unless they were hauling freight somewhere.

"What reason do they give?" she asked.

"They say they're waiting for a shipment of jewelry coming from Ghatotkacha. That's a planet . . ." he squinted at the screen, trying to find the data.

"It's the second planet of Epsilon Virgo, over in Gupta Sector," said Trimm. The request for such a long orbital stay made sense, now. Gupta Sector was rather isolated and the only easy access to the big markets of the League was through the Visigoth Junction. Given the notorious fussiness of Visigoth's customs service, any freighter captain with half a brain who needed to spend idle time in orbit waiting for a shipment to arrive would choose to do so at the Mesan end of the terminus.

Gupta Sector was known for its jewelry, and jewelry was one of the high value freight items that a freighter would be willing to wait for. Provided . . .

"Send them a message, Gansükh. I want to see the financial details of their contract of carriage. Certified data only, mind you. We're not taking their word for it."

From the frown on his face, it was obvious that Blomqvist didn't understand why she wanted that information.

"For your continuing education, young man. The financial section of their contract of carriage should tell us who's paying for their lost time in orbit. The shipper of origin? Or it could even be the jewelers themselves. Or the final customer, or their broker. Or . . ."

His face cleared. "I get it. Or maybe they're eating the cost themselves. In which case . . ."

"In which case," E.D. said grimly, "were sending a pinnace over there with orders to fire if they don't allow a squad of armored cops aboard to search that vessel stem to stern. There's no way a legitimate gypsy would agree to swallow the cost of spending that much time in orbit, twiddling their thumbs."

"What's a stem?" he asked, as he sent the instructions to the Hali Sowle. "I thought it was part of a plant. So why would it be connected to a starship?"

Since he couldn't see her face, she let her eyes roll. At least she'd only have to put up with the ignoramus for another three days before the shifts were restructured. If she got lucky, she might even be partnered next time with Steve Lund. Now, there was a man with whom you could have an intelligent conversation. He had a good sense of humor, too.

"Never mind, Gansükh. It's just a figure of speech."

She sometimes thought that for Gansükh Blomqvist, the whole damn universe outside of his immediate and narrow range of interests was a figure of speech. Oh, well. She reminded herself, not for the first time, that every hour she spent bored by Blomqvist's company piled up just as much in the way of pay, benefits and retirement credit as any other hour on the job.

* * *

"And there it is, Ganny," said Andrew Artlett admiringly. "Just like you predicted. How do you know these things, anyway?"

Elfride Margarete Butre smiled, but gave no answer. That was because the answer would have been heart-breaking for her. She knew the many things she did which almost none of her descendants and relatives did, for the simple reason that she'd had a full life prior to being stranded on Parmley Station—where most of them had spent their entire lives there.

For some considerable part of that pre-Station life, she and her husband had been very successful freight brokers. That was how they'd amassed their initial small fortune, which Michael Parmley had then parlayed into a much larger fortune playing the Centauri stock exchange—and then blown the whole thing trying to launch a freight company that could compete with the big boys in the lucrative Core trade.

Читать дальше