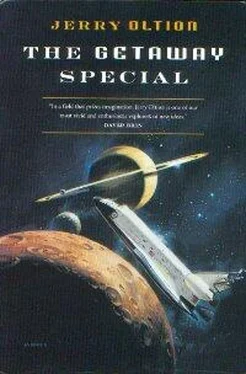

The Getaway Special

by Jerry Oltion

Special thanks to Eleanor Wood for being wonderful, Bob Gleason for being patient, the Oregon Writers Colony for refuge from the real world, and Pat Dooley for writing a computer program to calculate the Tangential Vector Translation Maneuver.

I owe you an explanation.

If you’ve read another book of mine called Abandon in Place , you’ve met a character named Allen Meisner. He’s a genuine mad scientist, a card-carrying member of the International Network of Scientists Against Nuclear Extermination, and he helped a couple of astronauts figure out how to make a spaceship out of goodwill and wishful thinking.

He’s in this book, too. In fact, he actually came from here first. The first section of this book predates Abandon in Place by about fifteen years. I wrote it as a short story back in 1984, and it was published in Analog magazine in April of ’85.

That was before the Soviet Union collapsed and the Berlin Wall came down. The Cold War was still in full swing, and people were afraid the world could go up in a mushroom cloud at any moment. I wanted off the planet, and I wanted off now . From that impetus, “The Getaway Special” was born.

People liked the story. They kept asking me to write a novel based on it. I tinkered with it a little here and there, but years passed without much progress. In the meantime I wrote Abandon in Place , and I needed a mad scientist for that book, so I borrowed Allen from here. Never mind that the two books describe wildly different universes; Allen seemed adaptable enough, and he wasn’t doing much over here. He had to leave his invention behind, but that was okay, too; there was plenty of wonky science for him to do in Abandon .

But playing with Allen again got me to thinking about The Getaway Special, and Tor expressed an interest in publishing it, so here I am writing it after all. The world is a different place than it was when I wrote the original short story, and Allen has been living in an alternate universe for a while, but that’s okay. Reality has never been all that easy to pin down anyway.

The short story that started everything became the first part of this book. I adjusted it for the politics of the day, but there was surprisingly little change necessary. The Soviet Union may not be the Evil Empire anymore, but the pieces it left behind are still a nuclear threat—in many cases a more dangerous threat than the parent country. The International Space Station that we were talking about building in the ’80s is still not up and running, and nobody seems to know what we’ll call it when (if) it is. The space shuttle is still our only way to put people into orbit, despite the steady aging of the fleet. And so on.

In 1984, Allen Meisner saw all this and said, “Enough!” Now it’s 2000 and he’s back from a consulting job in another universe, still eager to get on with the business of busting humanity out of the cradle. So am I. I’m glad to have him back.

Allen Meisner didn’t look like a mad scientist. He not only didn’t look mad, with his blonde hair neatly brushed to the side and his face set in a perpetual grin, but—at least in Judy Gallagher’s opinion—he didn’t look much like a scientist, either. He looked more like a beach bum.

But his business card read: “Allen T. Meisner, Mad Scientist,” and he had the obligatory doctorate in physics to go with it. He also had a reputation as an outspoken member of INSANE, the politically active International Network of Scientists Against Nuclear Extermination, and he held patents on half a dozen futuristic gadgets, including the electron plasma battery that had revolutionized the automobile industry. He had all the qualifications, but he just didn’t look the part.

That was all right with Judy. In her five years of flying the shuttle, most of the passengers she had taken up had looked like scientists, or worse: politician’s. She enjoyed having a beach bum around for a change.

Right up to the time when he turned on his experiment and the Earth disappeared. She didn’t enjoy that at all.

It started out as a routine satellite deployment and industrial retrieval mission, with two communications satellites going out to geostationary orbit and a month’s supply of processed pharmaceuticals, optical fibers, and microcircuits coming back to Earth from Space Station Freedom . It was about as simple as a flight got, which was why NASA had sent a passenger along. Judy and the other two crewmembers would have time to look after him, and NASA could reduce by one more the backlog of civilians who had paid for trips into orbit.

Another reason they had sent him was the small size of his experiment. Since the shuttles had begun carrying pay-loads both ways there wasn’t a whole lot of room for experiments, which meant that most scientists had to wait for a dedicated Spacelab mission before they could go up, but Allen had promised to fit everything he needed into a pair of getaway special canisters—small cylinders designed for schoolkids’ experiments and the like—if NASA would send him on the next available flight. After all the bad publicity they’d gotten for nationalizing the space station and carrying the laser and particle beam weapons into orbit, they’d been glad to do it. It would give the press something else to talk about for a while.

They had even stretched the rules a little in their effort to launch a scientific mission. Most getaway specials were allowed only a simple on/off switch, or at most two switches, but they had allowed Allen to plug a notebook computer into the control line for his. It had seemed like a reasonable request at the time. After all, he would be there to run it himself; none of the crewmembers needed to fool with it.

Officially his was a “Spacetime Anomaly Detection and Transfer Application Experiment.” One of the two canisters was simply a high-powered radio transceiver, but the other was a mystery. It contained a bank of plasma batteries with enough combined power to run the entire shuttle for a month, plus enough circuitry to build a supercomputer, all wired together on a hobbyist’s integrated circuit board three layers deep. That in turn was connected to a spherically radiating antenna mounted on top of the canister. Rumor had it that someone in the vast structure of NASA’s bureaucracy knew what it was supposed to do, but no one admitted to being that person. Still, someone in authority had vouched for it, and it apparently held nothing that could interfere with the shuttle’s operating systems, so they let it on board. It was Allen’s problem if it didn’t work.

So on the second day of the flight, as Mission Specialist Carl Reinhardt finished inspecting the last of the return packages in the cargo bay with the camera in the remote manipulator arm, he said to Allen, “Why don’t you go ahead and warm up your experiment? I’m about done here, and you’re next on the agenda.”

Discovery , like all the shuttles, had ten windows; six wrapping all the way around the flight controls in front, two facing back into the cargo bay, and two more overhead when you were looking out the back. Allen was blocking the view out the overheads; he’d been watching over Judy’s shoulders while she used the aft reaction controls to edge the shuttle slowly away from the space station and into its normal flight attitude. He nodded to Carl and pushed himself over to the payload controls, a distance of only a few feet. In the cramped quarters of the shuttle’s flight deck nearly everything was within easy reach. It was possible— if you floated with your feet in between the pilot’s and copilot’s chairs and your head pointed toward the aft windows—to strand yourself without a handhold, but to manage it you had to be trying. Allen had put himself in (hat position once earlier in the flight, and he’d gotten the worst case of five-second agoraphobia that Judy had ever seen before she could rescue him. After that he kept a handhold within easy reach all the time.

Читать дальше