Jeffrey Lord - Slave of Sarma

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jeffrey Lord - Slave of Sarma» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Героическая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

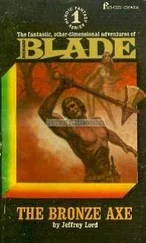

- Название:Slave of Sarma

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Slave of Sarma: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Slave of Sarma»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

__________________________________________

Blade's newest mission: Projection by computer to Dimension X, to track down and kill the russian agent posing as his double.In Sarma, land of weird customs and barbaric punishments, he could survive only by satisfying the cravings of the royal women. Failure ment live burial, or being hurled into the flaming jaws of Bek-Tor. And always the danger from the man who was his double...and might prove to be his final destruction.

Slave of Sarma — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Slave of Sarma», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jeffrey Lord

Slave of Sarma

Chapter One

It had been misting all day and, as London's lights began to go on early, a dark brown fog crept in from the Thames. Pavements were shiny and treacherous, slimed by fallen leaves. Fog horns on the river were raucous and surly, their mood matched by that of millions of Londoners as they began the vespertine shove into tube and train and car. A dour day, in all, with Indian summer gone and the drear of winter upcoming.

At 391/2 Prince's Gate, Kensington, the mood was no less dour.

The house was tall and narrow, of early Victorian vintage. It had been in Lord Leighton's family since he could remember. But because it was at times rented, at times idle, His" Lordship was inclined, until reminded by his agents, to forget that he owned it. The district was no longer fashionable - a matter of little concern to Lord L, who was not very fashionable himself - and it was J who had seen the possibilities. J ran the affairs of MI6A, a most special branch of the Special Branch. J was also immediate superior to Richard Blade, who at the moment was at his cottage in Dorset and, with another foray into Dimension X coming up, was not alone.

J was not thinking of Blade. He sat by a glowing coal fire, a glass of scotch and soda balanced on one impeccably clad knee, and watched the two men duel. J's money was on Lord Leighton, but he had to admit that the Right Honorable Hubert Carrandish was no mean opponent. Carrandish was a Member of Parliament from the West Riding area in Yorkshire, and he reminded J of a well-dressed and articulate rodent. J, a fair man, did not go so far as to equate the MP with a rat; there were, after all, other species of rodent. As he listened, keeping out of the battle, J felt himself becoming increasingly liverish. What the Yanks called an upset stomach. This Carrandish, with his broad Yorkshire speech - surely an affectation, because the man was Oxford - was dangerous. Not in himself, perhaps, but in what he represented. Snooping.

The Right Honorable gentlemen was chairman of a committee. A House of Commons committee set up expressly to scrimp and save and cut corners and, in effect, to halt waste and preserve the Queen's Purse. He was very good at his job.

Now he said, "I have a great deal of authority, Your Lordship, and more than adequate funds and personnel. I pride myself that I work hard. I have been nearly a year on this job. I have had, I think, more than a little success in ferreting out waste and extravagance in government."

Lord L dumped cigar ash on the carpet and stared at the man with yellow bloodshot eyes. Never a patient man, and not taking to fools, so far he had been patient. J knew why. This Carrandish was no fool.

"What you manage to save," Lord L said, "will just about pay for the cost of saving it, eh? That's been my experience. You chaps organize your bloody committees to investigate other committees and the end result is that in the end nothing is saved. Or accomplished. Time and money spent and nothing to show for it, eh?"

J smiled at the fire. Lord L was trying to lay a false trail.

The MP from Yorkshire was having none of it. He was not a drinking man, or a smoking man - possibly because both cost money which could be better spent - and now he pushed away his untouched glass and an empty ashtray and leaned over the table toward His Lordship. He clasped his long bloodless fingers and his eyes, fairly close to a long nose, glinted at the old man in the ragbag suit.

"None of that, sir, is relevant. As you must know. This interview was arranged, with your very gracious permission, so that we might speak in private and without public record. I came, in fact, to ask you one specific question."

Lord Leighton brushed a wisp of white hair away from his high balding forehead. He sat a little sideways in the tall-backed chair - this eased the eternal pain in his hump - and his leonine eyes studied his inquisitor with a mingle of wariness and contempt.

J felt a moment of compassion. This was his work, really, not Lord L's. Yet he could not intervene, even if circumstances had allowed it. Lord L had warned J, in no uncertain terms, to butt out!

"Then," said Lord Leighton, sounding like a much-tried and very patient lion, "get on with it, man. Ask your bloody damned question and get it over with."

J began to feel a little sorry for the Right Honorable gentleman. Lord L's temper was beginning to slip.

Carrandish was not an easy man to bully. He slapped his hand on the shiny surface of the table and some of the respect in his tone had gone.

"I have asked the question, Your Lordship. I have asked it at least six times and in half a dozen ways. So far I have received no intelligible answer."

Lord Leighton reached for a box of cigars. "Are you implying, sir, that I have gone bonkers? It is possible, I suppose. I am an old man and I work very hard. Long hours, you know. I get very little sleep, not nearly what my doctor tells me I need, and I never have eaten well and then of course there are all the aches and pains that come with old age. Our brains begin to deteriorate as we grow older and - "

The MP's patience had already deteriorated. He shrugged his narrow shoulders. His smile was gelid, his gaze flinty, as he said, "That is just what I mean, sir."

Lord L, still holding on to his temper, contrived to look like an idiot. "Mean? Mean what? I don't understand what you mean. Not at all. Not to be wondered at, I suppose. None of you young people know how to talk these days. Nor write, for that matter. Can't think what they teach up at the schools these days. Now in my time - "

J suddenly understood that the MP had received a reprieve. The storm was being held off. Lord L was enjoying himself.

Carrandish was not. J watched with interest as the man made one last great effort.

"I had no intention of implying, sir, that you have gone, er, bonkers. Not at all. I merely - "

"Senile," said Lord L cheerfully. "I suppose that must be it. Pity, but it comes to all of us. And now, Mr. Carrandish, I am afraid I must ask you to excuse me. I am tired and I am sure you have other things to do, more important things, than talking to a doddering old wreck like me."

The MP raised his eyes and stared at the ceiling beams for a moment. J struggled with his desire to laugh.

But the MP was tough. "I would like to put the question to you once more, sir, if you don't mind. Just one last time. I may?"

"What question?"

Carrandish closed his eyes as if in silent prayer.

"With your permission, sir. Once again - I have isolated some three million pounds. What we on the committee refer to as vagrant funds."

"I like that," said His Lordship. "Vagrant funds. Very well stated. Good use of language. Maybe I did you young people an injustice."

Carrandish raced ahead, his eyes glazing and a dew of perspiration on his pale brow: "Some of the vagrant funds quite naturally gravitate to Secret Funds, sir. That is well known and is not questioned. But there are vouchers and they must be signed and the entire process of vouchering must be carried out to its final conclusion so that Her Majesty's books can be balanced: I am sure, Lord Leighton, that you see this."

His Lordship, who hated shaving, stroked a stubbled chin with fragile, liver-spotted hands. He smiled. And when this old man, this high boffin, this chief of all Britain's scientists, smiled, he could be very charming indeed.

He nodded. "I can see that, Mr. Carrandish. Indeed yes. Any fool, and I am not quite that yet, can see that we can't have all those pounds lying around unaccounted for. What I don't see, Mr. Carrandish, is why you come to me?"

Mr. Carrandish pounced. J admitted his error. The man was no rodent. Mustela furo. The weasel family.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Slave of Sarma»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Slave of Sarma» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Slave of Sarma» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.