Juliet’s parents died when she was twelve and she was sent to live with her great-uncle, Dr. Roderick Ashton, in London. Though not an unkind man, he was so mired in his Greco-Roman studies he had no time to pay the girl any attention. He had no imagination, either—fatal for one engaged in child-rearing.

She ran away twice, the first time making it only as far as King’s Cross Station. The police found her waiting, with a packed canvas carry-all and her father’s fishing rod, to catch the train to Bury St. Edmunds. She was returned to Dr. Ashton—and she ran away again. This time, Dr. Ashton telephoned me to ask for my help in finding her.

I knew exactly where to go—to her parents’ former farm. I found her opposite the farm’s entrance, sitting on a little wooded knoll, impervious to the rain—just sitting there, soaked—looking at her old (now sold) home.

I wired her uncle and went back with her on the train to London the following day. I had intended to return to my parish on the next train, but when I discovered her fool of an uncle had sent his cook to fetch her home, I insisted on accompanying them.

I invaded his study and we had a vigorous talk. He agreed a boarding school might be best for Juliet—her parents had left ample funds for such an eventuality.

Fortunately, I knew of a very good school—St. Swithin’s. Academically a fine school, and with a headmistress not carved from granite. I am happy to tell you Juliet thrived there—she found her studies stimulating, but I believe the true reason for Juliet’s regained spirits was her friendship with Sophie Stark and the Stark family. She often went to Sophie’s home for half-term vacation, and Juliet and Sophie came twice to stay with me and my sister at the Rectory. What jolly times we shared: picnics, bicycle rides, fishing. Sophie’s brother, Sidney Stark, joined us once—though ten years older than the girls, and despite an inclination to boss them around, he was a welcome fifth to our happy party.

It was rewarding to watch Juliet grow up—as it is now, to know her fully grown. I am very happy she asked me to write to you of her character.

I have included our small history together so you will realize I know whereof I speak. If Juliet says she will, she will. If she says she won’t, she won’t.

Very truly yours,

Simon Simpless

Susan Scott to Juliet

17th February, 1946

Dear Juliet,

Was that possibly you I glimpsed in this week’s Tatler, doing the rumba with Mark Reynolds? You looked gorgeous—almost as gorgeous as he did—but might I suggest that you move to an air-raid shelter before Sidney sees a copy?

You can purchase my silence with torrid details, you know.

Yours,

Susan

Juliet to Susan Scot

18th February, 1946

Dear Susan,

I deny everything.

Love,

Juliet

From Amelia to Juliet

18th February, 1946

Dear Miss Ashton,

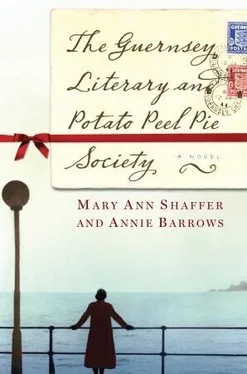

Thank you for taking my caveat so seriously. At the Society meeting last night, I told the members about your article for the Times and suggested that those who wished to do so should correspond with you about the books they read and the joy they found in reading.

The response was so vociferous Isola Pribby, our Sergeant-at-Arms, was forced to bang her hammer for order (I admit that Isola needs little encouragement to bang her hammer). I think you will receive a good many letters from us, and I hope they will be of some help in your article.

Dawsey has told you that the Society was invented as a ruse to keep the Germans from arresting my dinner guests: Dawsey, Isola, Eben Ramsey, John Booker, Will Thisbee, and our dear Elizabeth McKenna, who manufactured the story on the spot, bless her quick wits and silver tongue.

I, of course, knew nothing of their predicament at the time. As soon as they left, I made haste down to my cellar to bury the evidence of our meal. The first I heard about our literary society was the next morning at seven, when Elizabeth appeared in my kitchen and asked, “How many books have you got?”

I had quite a few, but Elizabeth looked at my shelves and shook her head. “We need more. There’s too much gardening here.” She was right, of course—I do like a good garden book. “I’ll tell you what we’ll do,” she said. “After I’m done at the Commandant’s Office, we’ll go to Fox’s Bookshop and buy them out. If we’re going to be the Guernsey Literary Society, we have to look literary.”

I was frantic all forenoon, worrying over what was happening at the Commandant’s Office. What if they all ended up in the Guernsey jail? Or, worst of all, in a prison camp on the continent? The Germans were erratic in dispensing their justice, so one never knew which sentence would be imposed. But nothing of the sort occurred.

Odd as it may sound, the Germans allowed—and even encouraged—artistic and cultural pursuits among the Channel Islanders. Their object was to prove to the British that the German Occupation was a Model Occupation. How this message was to be conveyed to the outside world was never explained, as the telephone and telegraph cable between Guernsey and London had been cut the day the Germans landed in June 1940. Whatever their skewed reasoning, the Channel Islands were treated much more leniently than the rest of conquered Europe—at first.

At the Commandant’s Office, my friends were ordered to pay a small fine and submit the name and membership list of their society. The Commandant announced that he, too, was a lover of literature might he, with a few like-minded officers, sometimes attend meetings?

Elizabeth told them they would be most welcome. And then she, Eben, and I flew to Fox’s, chose armloads of books for our newfound Society, and rushed back to the Manor to put them on my shelves. Then we strolled from house to house—looking as carefree and casual as we could—in order to alert the others to come that evening and choose a book to read. It was agonizing to walk slowly, stopping to chat here and there, when we wanted to scurry! Timing was vital, since Elizabeth feared the Commandant would appear at the next meeting, a bare two weeks away. (He did not. A few German officers did attend over the years but, thankfully, left in some confusion and did not return.)

And so it was that we began. I knew all our members, but I did not know them all well. Dawsey had been my neighbor for over thirty years, and yet I don’t believe I had ever spoken to him of anything more than weather and farming. Isola was a dear friend, and Eben, too, but Will Thisbee was only an acquaintance and John Booker was nearly a stranger, for he had only just arrived when the Germans came. It was Elizabeth we had in common. Without her urging, I would never have thought to invite them to share my pig, and the Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society would never have drawn breath.

That evening when they came to my house to make their selections, those who had rarely read anything other than Scripture, seed catalogues, and The Pigman’s Gazette discovered a different kind of reading. It was here Dawsey found his Charles Lamb and Isola fell upon Wuthering Heights . For myself, I chose The Pickwick Papers, thinking it would lift my spirits—it did.

Then each went home and read. We began to meet—for the sake of the Commandant at first, and then for our own pleasure. None of us had any experience with literary societies, so we made our own rules: we took turns speaking about the books we’d read. At the start, we tried to be calm and objective, but that soon fell away, and the purpose of the speakers was to goad the listeners into wanting to read the book themselves. Once two members had read the same book, they could argue, which was our great delight. We read books, talked books, argued over books, and became dearer and dearer to one another. Other Islanders asked to join us, and our evenings together became bright, lively times—we could almost forget, now and then, the darkness outside. We still meet every fortnight.

Читать дальше