“Bess, my little starling,” he rumbled as she worked to open its lid. “These cards are most special; they belonged to your father, a wonderful man, and in them are the keys to all the world. It is time you were instructed. I’ve heard from my son, Zachary. Our friend Benno has found you a guide. Her name is Katya, and she is the daughter of your father’s teacher.”

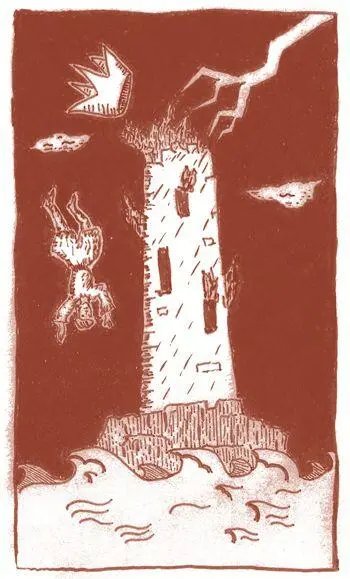

Bess’s soft fingers touched the orange deck, flipping over the first card. Lightning and flames — a broken sky. The Tower.

With morning comes pounding. We survived the night. Alice is at the front door, knocking on the glass with her forearm. She is in tall green rubber boots, practical as ever.

Enola rouses when I shake her. She smacks Doyle awake.

“Come on,” I say. “Help me move the coats so we can let Alice in.”

“She’s here? I thought we were leaving her the keys.”

“She probably just wanted to check in.” We move the chairs and throw the coats and sweaters aside, each landing with a saturated thud on the wet carpet. Outside, Alice is bouncing on her toes. Something is very wrong. We open the door.

“Oh God,” she says. “It flooded in here? How bad is it?”

The books. Of course, she’s here for the books. I didn’t know I’d wanted her worried about me until I’d been supplanted by books. “Downstairs got the worst of it. I kept whatever I could dry. I stopped the back door, but there wasn’t much we could do. I’m sorry. The whaling archive is safe, though.”

“Of course it is. In the archive we trust.” The words are joyless. She looks me up and down. “Are you all right?”

“Sure,” I say. Then her arms are around me in a quick hug, warm and good. She’s still in her pajama bottoms. “Are you okay?”

She takes a breath and holds it. In middle school the girls used to have contests to see who could hold their breath the longest; Alice once held it until she fainted. Her words shoot out all at once. “You have to come with me. Your house is going over and you need to get whatever you can out of it now.”

She says something else, but I can’t hear it because Enola is saying, “Shit, shit, shit.”

“It’s bad?” I ask.

“It’s bad. The roads are still flooded. My dad told me to get you. He kept calling and calling, and I didn’t want to pick up but I thought it could be my mother.” She tugs on her hair, wringing it out. “I’m really sorry. Look, I brought the truck. If you follow me I’ll take you back where the roads are good. You can put anything from the house in the truck.”

The water is more than ankle deep through the lot. We pile into my car and slowly move through the flooding, with Alice leading in Frank’s flatbed. She must have picked it up from him, which means she’s seen the house. She leads us nearly to the center of the island. Port must still be closed off.

Enola continues quietly swearing.

“You have a chance to get stuff,” Doyle says. “That’s good.”

We follow Alice’s taillights up Middle Country Road. Cars are stranded on either side — a ghost town of vehicles. She turns us toward the water, heading north, taking side roads around downed trees. When we reach Till Road, Enola starts to cry.

Alice pulls into Frank’s driveway and I park alongside her. I tell myself not to look until we get out of the car and can stare it in the face.

* * *

The house is in silhouette, hanging off the cliff’s edge, tilting like an Irishman’s cap. We stand beside it, four tiny figures, no more than paper dolls, two huddled together, the smallest spark dancing between their bodies. Children at the gates of our history.

“Throw whatever you can get in the truck and come back to my place,” Alice says. “You can stay with me.”

“Thanks,” I say. “It won’t be forever.”

“We’ll work it out.” She gives my hand a squeeze. “I need to talk to my mom.” She walks toward the house where she grew up, and for a minute I don’t know who has it worse, and then I do. It’s Alice.

Enola tells Doyle to wait by the car. “This is excavation. Watsons only.”

Though he says cool, he conveys be careful.

* * *

The door hangs off its hinges and the hole in the living room floor has become a pit. A wide split spiders up the wall between the kitchen and living room. I can see Mom’s hand wrapping around the corner, laughing as she ran down the hallway. We walk around the edge of the room, balancing against things — the couch — I can remember Enola hiding behind it, giggling — my desk, anything that will take weight. Enola sees me limping and offers her shoulder.

“Get that picture,” she says, pointing. “The one of me and Mom.”

“Frank took that.”

“Get over it.” She yanks it from the wall. My grown sister hands me her child self. “You’re going to want it.”

“You don’t want anything?”

She shakes her head. “You know I never asked you to stay, right? When it’s gone I think you should just forget it was ever here. Be happy, okay?”

A sharp whining screams down the hallway. We tense. Her fingers dig into my shoulder. The sound deepens to a low howl, then crashing. I clap my hands over my ears, but it’s too late. Enola mouths something— what the fuck . Plaster showers over us. I yell, “Run,” as the floor begins to roll. I tuck my head to my knees. Tossed against the front wall, back slammed into the desk. A sucking spasm. Emptied out. A great tearing sound. A chair topples. Glass shatters. Papers and books tumble onto me. Air, air pushes up from under.

The sound dies and the floor stops moving. My ears buzz. The room is thick with dust. Enola is huddled in the corner by the sofa, covered in papers, shaking.

“Fuck! Are you all right? Everybody all right?” Doyle is in the doorway, streaming nervous chatter. Daylight comes from the hall through the dirt and debris. Tentacled arms lift Enola, me, pulling us onto what’s left of the lawn and into the whipping grass; his grip has the bite of electricity.

* * *

We wind up on the hood of my car. The damage is incredible. The side of the house collapsed, spilling the contents of my parents’ bedroom across the cliff, along with bits and pieces of the stone foundation. The bed traveled farthest, mattress hidden among the beach grass, headboard kissing the remnants of the bulkhead, and Dad’s shoes toppled down the bluff until they bounced their way into the water. I wanted to throw them out, but I could never bring myself to.

The crabs are still here. They should be gone. They should have left after I’d burned Frank’s things and the book. Or rolled out with the tide as the storm that took my house pulled back. It’s stronger now, the feeling that I’ve missed something. Papers are scattered everywhere — leaves or snowflakes — pieces of my family thrown to the wind. Why are the crabs here? Was burning not enough?

“Is that Mom’s typewriter?” Enola asks. It is, banked against a scrub pine along with what must be manuals. A piece of chimney falls. Down the cliff, Dad’s tools dig themselves into the sand. It’s gone. All of it.

Enola takes her cards from her pocket. In the light of day they’re brown and worn, edges rounded out until there’s almost nothing left at all. They’re nearly pulp, worn by skin oils — hers, Mom’s, other people’s. They smell like dust, paper, and women. She sets them beside her on the hood of the car. Doyle hops down and begins pacing.

“Put those away, Little Bird.”

“No.” To me she says, “Cut.”

Читать дальше