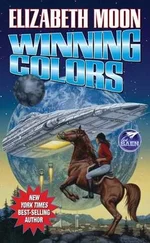

“They won’t catch you on that horse,” said the Marshal. “But I’ll see if I can delay them.”

Paks nodded, and reined the red horse around. He shook his head, fighting the rein as he never had, and moved out stiffly when she nudged him. In a few lengths he tried to sidle back toward the Marshal. Paks bumped him harder with her heels, and wondered what he thought he was doing. Then a horn signal floated across the air, and she froze. It couldn’t be. In a single motion, she reined the horse around yet again, and galloped toward the oncoming riders. She heard the Marshal yell her name as she rode by, but did not stop or reply.

Again the horn call: incredibly, the call she knew so well. She rode on; the red horse slid to a stop just in front of the cohort’s commander, who was already braced for an attack.

“You!” Dorrin’s voice was hardly recognizable.

“I don’t believe it,” said Paks, believing it. The horn spoke again, and ninety swords slipped back into their scabbards.

Dorrin reached out to grip her arm. “It is really you? The Duke said—”

“It is. And this is you, and how—”

Dorrin pushed up her visor. “We,” she said, “are not the Tsaian Royal Guard. It doesn’t take my cohort two days to pack and ride.”

“I thought he left that night.”

“He did, but I nearly had to pack every Tir-damned mule myself. And a third of their heavy horses needed new shoes, and so on. It’s a wonder I have a voice left.”

“And?” Paks had turned the red horse, and they were jogging together at the head of the column.

“And as soon as he got back, he sent Selfer north, to pick up my cohort.”

“All the way to the stronghold?”

“No-o. Not quite. In case of any difficulty, he’d stationed them along the southern line.”

They were riding through Westbells now, and Paks waved to Marshal Torin, who stood watching with an uncertain expression. She pulled the red horse out of line, and went to him.

“It’s Dorrin’s cohort of Phelan’s company,” she said quickly. “They’ve come to help.”

“I gathered it was his, from the pennant,” he said. “By Gird, they move fast. When did they leave the north?”

“I don’t have the whole story yet,” said Paks. “Someday—” And she turned again and rode after them, for the column was past already. Again at the head of it, riding into the rising sun, Paks felt at home.

Dorrin reined her horse close to Paks’s. “Paks, I never expected to see you again, let alone riding at my side this day. And you look—I have never seen you looking better. How did you get free of them? And that mark—”

“Gird’s grace,” said Paks. “I can’t explain it all, but they kept their bargain, at least to leaving me alive. Then the gods gave healing: that mark began as Liart’s brand. I presume,” she said with a sidelong glance, “that they had more for me to do. Something is stirring the Thieves Guild; they had a part in it.”

Dorrin nodded. “The Duke—the king—blast, I must get that straight in my mind—anyway, he said something about the Thieves Guild. They wouldn’t let the Liartians kill him there, he said. But how did that help you?”

“Oh—a couple of years ago, after I left the Company, I met a thief in Brewersbridge.” Dorrin grunted, and Paks went on. “A priest of Achrya had set up a band of robbers in a ruined keep near there, and the town hired me to find and take them. This thief—he said he was after the commander, because they hadn’t been paying their dues to the Guild.”

Dorrin shook her head. “I have a hard time imagining a paladin of Gird with a thief for a friend.”

Paks thought of Arvid. “Well—he’s not a thief—exactly. Or my friend, exactly, either.” Dorrin looked even more dubious; Paks went on. “So he says. Obviously he’s high in the Guild, but he’s never said exactly what he does do. He’s not like any thief I ever heard of. But in this instance, he saved my life. He’s the one who arranged to have me taken outside the city, alive or dead, when the time was up. And he killed someone who had bargained to kill me.”

Dorrin turned to look at her. “A thief?”

“Yes.” Paks wondered whether to tell Dorrin that Gird had as much interest in thieves as kings, but decided against it. A knight of Falk, born into a noble family, had certain limitations of vision, even after a lifelong career as a mercenary captain.

“Hmmph. I may have to change my mind about thieves.” From Dorrin’s tone, that wasn’t likely. Paks laughed.

“You needn’t. Arvid’s uncommon.”

“He’s never robbed your pocket,” said Dorrin shrewdly.

“No. That’s true. Just the same, he took no advantage when he might have, in Brewersbridge, and he served me here.” She rode a moment in silence, squinting against the level rays of the rising sun. “What does the king expect, that he called your cohort in? And what did the Council think of it?”

Dorrin frowned. “He said they would never have released him if they hadn’t thought they could take him before the coronation. That they thought, with you out of the way, to attack somewhere on the road. The crown prince would have given him a larger escort, but he refused it . . . said it might be needed even in Vérella.”

“What does he have?”

“I suppose near seventy fighters altogether: a half-cohort of Royal Guards, the tensquad out of this cohort, those King’s Squires, the High Marshal and another Marshal. Plus supply and servants—an incredible amount, the Royal Guard insists on. It’s easy to see they don’t travel much.”

“Umm. I wish we had the whole Company.”

“So do I. But he said he couldn’t strip the north bare, not after the other troubles this winter. And Pargun might move, knowing him so far away. He did tell Arcolin to move the two veteran cohorts to the east and south limits, just in case. Val’s got the recruit cohort at the stronghold. He’s afraid that the evil powers will move with all violence.”

“And we have one cohort,” said Paks quietly. Dorrin smiled at her.

“And a paladin they didn’t expect us to have.”

“And two Marshals—perhaps more, if we’re near a grange. That is, if we can catch up to them.”

“We will,” said Dorrin. “Those heavy warhorses won’t make a third the distance we’re making. And I daresay that red horse of yours could go even faster. Will you go ahead, then, or stay with us?”

Paks thought about it. “For now, I’ll stay with you. He has the Marshals with him; they will know, as I would know, if great evil is near. For all you are a Knight of Falk, Captain, I might be useful to you.”

“You know you are. I tell you, Paks, I was never so surprised—and relieved—as when you rode up. It harrowed all our hearts to go without trying to free you. But he said no one must do anything for five days.”

Paks nodded. “That was necessary.”

“But when I thought of it—” Dorrin shook her head. “Falk’s oath in gold! For anyone to be in their hands five days—and you—”

“It was necessary.” Paks looked over to Selfer, who had said nothing during all this. “How’s your leg?”

“It’s well enough,” said Selfer. “The Marshal took care of it, before I rode north.”

“How long did that take?”

“I left—let me think—well before midnight, and by dawn the third day I was with the cohort. We marched the next dawn—they were ready, but let me sleep until dark, and the Duke—the king—had said to march by day only, to Vérella.”

“He didn’t want the cohort too tired to fight,” said Dorrin. “We were to march out again at once. Selfer brought them in good shape—remarkable, considering the weather and all.”

Читать дальше