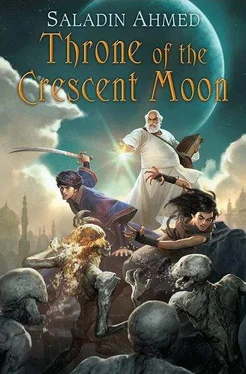

Adoulla didn’t know if it was his imagination or if there was really still a charred stink to the air of the block from the night before. He started to turn back to his townhouse—to make himself see the smoking shell of it. But he found he couldn’t quite force his feet eastward. To face that sight right now… He thought it might finally break him.

It was just as well. He could do nothing there, and maudlin wallowing wasn’t going to stop the monsters that were loose in his city.

Adoulla turned his steps to Gruel Lane. As he walked, he gingerly touched his chest where the sand ghul had slammed its ironlike arm into him. But the flesh there was no longer tender. Compared to the girl’s wound, his own bruises had been easy enough for his friends to heal. Adoulla shook his head, impressed yet again by his own poor fate. No matter how many times his extraordinary friends managed to patch him up, he ruminated, he always managed to show up again with a fresh wound.

He made his way to the great public garden and found a tiny hillock on which to sit, his bright white kaftan splayed around him. He loved this place that came to life at this late afternoon hour. It was nothing like the Khalif’s delicate gardens, where quietly chirping birds selected for their song dotted the branches of the orange and pomegranate trees that suffused the air with their soft scents. In the Khalif’s gardens, rippling brooks flowed magically upwards and filled the gardens with their lulling babble. No one there spoke above a whisper.

It was supposed to be soothing—the perfect place for princes, poets, and philosophers to be alone with their thoughts. But Adoulla, whose calling had more than once brought him to gardens that his station should have barred him from, thought he would go mad in such a place. For one, the tranquility was got by keeping the city’s rabble away at swordpoint. But there was more to it than that: He simply could not think in the Khalif’s gardens. He felt as if doing so might break something delicate.

The public garden of the Scholars’ Quarter, on the other hand, hosted some of the most riotous smells and sounds in all Dhamsawaat. Uppermost were piss, porters unwashed after a day of lifting in the sun, and a thousand kinds of garbage. But beneath these were layered the smells that said “home” to Adoulla—if anything in this unwelcoming world did.

As an orphan-boy, as a ghul hunter’s apprentice, as a young rascal and sometime hero, and now, as an old fart, he needed to breathe these scents. The brewing cinnamon-paint of the fortune tellers, the shared wine barrels of gamblers and thieves forgetting their troubles, the skewers of meat that dripped sizzling juices onto open fire pits and, here and there, a few flowers that seemed to be struggling to prove that this was a public garden and not a seedy tavern… Adoulla took it all in. Home.

Then there were the sounds. His calling had taken him many places, but Adoulla had yet to find a people as loud as those of his home quarter. The children and the mothers scolding the children. The roving storytellers and those who applauded and heckled them. The whores who offered warm arms for the night, and the men who haggled shamelessly with them. All of them going about their business in the loudest voices they could find. For cruel fate or kind, Adoulla thought, these were his people. He had been born among them, and he hoped very much to die quietly among them.

Bah. With your luck, old man, you’ll be slaughtered by monsters in some cold cavern, alone and unlamented.

For what seemed the hundredth time that week, Adoulla silenced the discouraging voice within and tried to focus on the problem before him. He sat and breathed and thought.

“Hadu Nawas,” the creature had said. The meaning of it was at the edge of his thoughts, but the harder he tried to grasp it, the more he felt like a man with oiled fingers clutching at a soapcake.

Baheem, an aging footpad who tried to rob Adoulla twenty years ago and, ten years ago, saved him from a robbery, walked past. He gave a friendly nod and pulled at his moustache, not bothering to speak, understanding that Adoulla was in meditation. Adoulla was known here, and that was why, of all places in the city, he could do what must be done here. Familiarity. It put him at ease, and when he was at ease he noticed things, put things together in their proper place.

Adoulla beckoned to Baheem, gesturing at a flat grassy spot beside him. His thoughts were not going where he needed them to, and trying to force them would only give him a headache. He knew from experience that distraction and idle chatter could help.

Baheem and he said God’s peaces and Baheem sat. The thick-necked man then produced a flintbox and a thin stick of hashi. “If you don’t mind, Uncle?”

Adoulla smiled negligently and quoted Ismi Shihab. “ ‘Hashi or wine or music in measure, God piss on the man who bars other men’s pleasure.’ ”

Stinky sweet, pungent smoke soon surrounded the pair as they sat talking about nothing and everything—the weather, neighborhood gossip, the succulent shapes of girls going by. Baheem offered the hashi stick to him more than once, and though Adoulla refused each time, he could feel the slightest hint of haze begin to creep in at the corners of his mind just from sitting beside Baheem.

It was pleasant, and Adoulla happily let his thoughts get lost in the rhythm of Baheem’s complaints. For a few moments he managed to almost forget all of the grisly madness that filled his life.

“I’ve heard a pack of the Falcon Prince’s men were found dead in an ambush,” Baheem said. “Word is, their hearts were torn from their chests! It has to have been the Khalif’s agents, though you think they’d have gone for the public beheadings they love so much.”

Adoulla’s distracted half-cheer evaporated. Hearts torn from their chests? He struggled to think through his secondhand hashi haze. It sounded as if the Falcon Prince faced the same foe as Adoulla and his friends. And Pharaad Az Hamaz could prove a powerful ally in this. Adoulla started to ask about this, but Baheem was on a hashi-talkative roll now, his complaining uninterruptable.

“And then there’s the damned-by-God watchmen and this dog-screwing new Khalif!” the thief said quietly but forcefully, punctuating each word with a pull of his moustache. “These rules they have! Take the other day. I’m trying to move goods through Trader’s Gate for my sick old Auntie—” he smiled shamelessly “—and two watchmen stop me, asking for a tax pass. Now, of course, I have a tax pass. An almost legitimate one! But these sons-of-whores start talking about new taxes and tariffs on this gate and that gate, at this rate and that rate, and pretty soon I’m headspun and copperless. Their rules and regulations are all hidden script to me, Uncle, but I know well enough when someone wants to starve my children to death. I—”

Hidden script and dead children! That’s it! God forgive me, why didn’t I think of it before? All his other thoughts fell away as Adoulla realized that Beneficent God had at last handed him a clue. “Of course! Curse my fuzzy-headedness, of course! That’s it!” Adoulla leapt up and grunted with the exertion of it. It was so sudden that Baheem actually stopped talking.

Baheem came to his feet more easily, clearly ready to fight despite the hashi-haze. “What is it, Uncle?”

“Baheem, my beloved, right now I am on a hunt that could kill me. And if that happens, many others in our city will die. But if it doesn’t happen, I owe you a night of feasting on the silver pavilion!”

Baheem had the good street sense to ignore the more dire part of Adoulla’s pronouncement. “The silver pavilion! I’d rather you just pay my rent for a month! If I knew I had information that valuable, Uncle, I would have sold it!”

Читать дальше