The Doctor stuttered, obviously trying to regain his wits. Raseed heard himself doing the same thing.

“Questions for later,” he heard Litaz’s voice say from somewhere. “Whoever she is, she’s dying here. We have to get her to our home, now . Raseed!”

He realized he’d been staring uselessly at Zamia’s unmoving form, her soot-stained face, and her closed, long-lashed eyes. Again he tried to speak, but his throat burned from smoke and tears. Ash caked his silks. “Auntie?” he finally managed.

The little Soo alkhemist’s voice was sharp, and her blue-black features were stern. “We’ve brought a litter,” she said, the rings in her twistlocked hair clicking as she nodded toward the wood and leather frame. “Help me carry it.”

His hands and feet moving without his seeming to will it, Raseed obeyed her command. As they lifted the litter, Zamia shrieked once in pain. Raseed felt as if the sound were tearing out his insides. Zamia grimaced and then fell silent.

“There’s hope here yet,” Litaz said. “ Move , boy!”

Raseed blinked away more tears, and he moved.

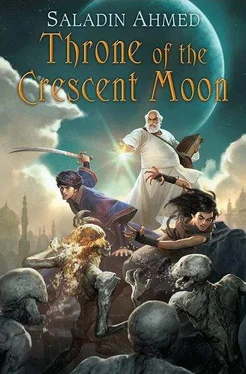

In the hour or so that was neither night nor morning, the Scholars’ Quarter of the great city of Dhamsawaat was quiet. The most indefatigable of the street people had finally gone to bed, even if bed was merely a bit of dirt lane. The first of the cart-drivers, porters, and shopkeepers would not hit the street for another hour or so. Litaz Daughter-of-Likami stared out her cedar-framed window, rubbing her temples and thanking Merciful God for small blessings—the soothing quiet had made the first part of her work a bit easier.

The busy, rough Scholars’ Quarter was usually so noisy that its name—a vestige of the city’s long past, Adoulla had told her—seemed an intentional irony. But Litaz prided herself that she, her husband, and their old friend Adoulla kept the bookish appellation from becoming a total lie. Ages after the neighborhood’s sages and students had been replaced by cheap shopmen and pimps, the three of them ensured that learning still lived in the Quarter. That their learning pertained to unnatural wounds and creatures made of grave-beetles made no difference.

Litaz turned from the window and considered the half-dead girl lying on the low couch before her, her coarse hair splayed across the cushions. The tribeswoman’s labored breathing was the loudest sound in the room. A sharp contrast to a few hours ago, when they’d come charging in with a dying, Angel-touched girl on a litter.

The wound was like none Litaz had ever seen. The tribeswoman had been bitten, though not so badly as to be life-threatening. But within the wound, it was as if the girl’s soul had been poisoned rather than her body. It didn’t fit any of Litaz’s formulae. Praise God that Dawoud—as he had in so many of their past healings—had intuited what to do. Her own tonics and wound poultices had stabilized the girl’s health. But it had been Dawoud’s powers—his mastery of the weird green glow that rose from within him as his hands snaked back and forth above the girl’s heart—that had truly brought her from the brink of death.

The smell of brewing cardamom tea brought her out of her thoughts. She could hear Dawoud in the next room, clinking cup against saucer for her. Making each other’s tea was half the reason they had such a happy marriage. It was one of the most important lessons of alkhemy, one that had stuck with her from the first days, when she’d left behind the stifling lifestyle of a Lady of the Soo court to pursue her training: Simple things ought not be taken for granted. She’d seen a horned monster from another world kill a man because of a small error in a summoning circle. She’d seen a husband and a wife grow to hate each other because they’d forgotten each other’s naming-days.

A shout came in the window from the street: a late drunk, or an early cartman. As if in response, the Badawi girl— Zamia , Adoulla had called her—made a pained noise. Litaz said a silent prayer for the girl and worried over the limits of her own healing-craft. She pulled a clay jar from one of the low visiting room shelves and scooped a handful of golden yam candies from it. The sweet, earthy flavor filled her mouth and calmed her. They were expensive, these tiny reminders of home, but there was nothing quite like them.

“You deserve the whole jar of them, hard as you have worked these past few hours. I think the girl will live because of it.” Her husband came into the room bearing a tea tray in his bony, careworn hands. Concern for her was etched on his wizened red-black face.

“Where are Adoulla and Raseed?” she asked.

He jutted his hennaed goatee at the stairway. “Both upstairs. The boy is in some kind of self-recriminating meditation. Adoulla is mourning his home and wracking his brain regarding this attack.”

Litaz had been doing the same since Adoulla had hurriedly explained that the girl was Angel-touched and described the creature that had attacked her. It would not be madness enough, some sliced-off, calloused part of her thought, for our Adoulla to bring us a dying Badawi girl. She would have to be a shape-changer, too. As though seized by her old friend’s soul, Litaz snorted out a bitter laugh. She took a teacup from Dawoud and sipped as she sat by the girl’s side.

The tribeswoman wore a pained grimace as she slept. Again Litaz found herself troubled by the strangeness of the girl’s malignant wound. For decades she had traveled with her husband and their various companions, dealing with creatures and spells that most men thought unfathomable. But Litaz knew that everything in this world could be analyzed. The ghuls, the djenn, balls of fire, and bridges made from moonrays. All of it made sense, if one understood the formulae. She had given up years ago on searching for liquors of agelessness and turning copper into gold that stays gold. Nor did she waste her talents on the stupid duties that employed the city’s handful of other master alkhemists. Working for weeks at a time to separate alloys or encourage crops—and make rich men richer—was not a way to spend a life, no matter the wealth such work might bring.

But helping hurt people was different. Looking at the girl’s wound again, Litaz once more set to work as an assessor-of-things. She had only ever read about soul-killing. It was new to her, though she knew it was an ancient magic. What mattered here, though, was that it had nearly killed a girl in the home of her and her husband’s closest friend. That made it their problem, too.

She set down her teacup and put a hand to the carved wooden clip that held up her long twistlocks. Dawoud, her opposite in so many ways, had often teased her that it was a fussy, Eastern Soo hairstyle. Years ago he’d proposed that she shave her head, like one of his red-black countrywomen from the Western Republic! The thought still horrified her.

Her husband stepped wordlessly to her side and put his hand on her back. She felt the pressure of his long, strong fingers and thanked God, not for the first time, that someone so unlike her could be such an inseparable part of her.

Litaz heard a noise on the stairs and turned to see Adoulla wearily making his way down them. Dawoud’s hand left her back, and he went over to embrace their friend. She didn’t really see the pain in Adoulla’s heavy-lidded eyes until she heard him speak in a voice not his own—the small voice of a weak man.

“My home. Dawoud, my home. It… it…”

He trailed off, his eyes shining with tears, and his big broad shoulders slumped. It troubled her to see Adoulla this way—he was not easily shaken. Her husband stepped back from embracing his friend and shook the ghul hunter by his shoulders.

Читать дальше