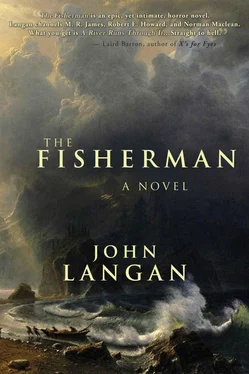

Already, Marie had moved uncomfortably far down the beach. I descended the hill. Stones clattered under my boots. To my left, the surf curled onto the beach with a hissing rumble, while further away, the ocean struck the rock wall with irregular booms. To my right, up the rise, the Vivid Trees maintained formation. A mile or so along the shore, the rock barrier swept in towards the shore, lifting into a cluster of large, jagged rocks. There was activity down there, a lot of it. Figures moved to and fro on the beach and, it appeared, in and out of the ocean — but I was too far removed to distinguish their actions.

I assumed Dan would be waiting for me, ahead. How he had found his way here, I couldn’t guess; though after what had befallen me, I supposed I shouldn’t have been too surprised at it. It seemed reasonable to imagine he’d encountered Sophie and his children, just as I’d met Marie. What it all meant was beyond me, which I knew was not a good thing, but which I hoped to delay reckoning with for as long as possible.

When we were still halfway there, I saw that the multitude of forms on the beach were the same fish-belly pale as Marie. I had no doubt the eyes of every last one of them would be gold. I was less certain of their features, and of what my reaction would be to a school of the creatures I’d glimpsed in Marie’s place. Their activity was focused on the heap of sharp stones that marked this end of the rock wall; as we closed to a quarter mile, I made out long ropes spanning the distance from stones to beach. There were dozens of thick ropes, each one attached to a different spot on what I saw was a much more substantial formation than I had appreciated, each one gripped by anywhere from five to ten of the white figures, at points ranging from far up the beach’s slope to well into the water. The ropes creaked with a sound like a big house in a bad storm. The forms holding them grunted and gasped with their effort.

That I could see, only one of the ropes was not held by ten or twenty hands. This rope ran from a horizontal crack in the formation near the water’s edge to a sizable boulder on shore, which the rope wrapped around three or four times. It was to this spot that Marie headed. Doing my best not to look directly at any of the pale shapes amongst whom I now was passing, I followed. Although having the knife in my hand lent me the illusion of security, I wasn’t sure if the things would take it as a provocation, so I slid my hand into the pocket of my raincoat and kept it there.

The boulder that was our destination was as large as a small house, a stone cube whose edges had been rounded by wind and time. We angled towards the water to reach the side of the rock that faced the ocean. In between watching my steps, I studied the pile of stone to which our goal was tethered. Separated from the beach by a narrow, churning strip of water, the formation was several hundred yards long, its steep sides half that in height. Its top was capped by huge splinters and shards of rock, the apparent remains of even larger stones that had been snapped by some vast cataclysm. The entire surface of the structure was covered in fissures and cracks. Some of the ropes the white creatures held were anchored in these gaps with what looked to be oversized hooks dug into the openings; while other ropes lassoed the ragged rocks on the formation’s crest. I could not guess what enterprise the multitude of ropes was being employed toward; their arrangement was too haphazard for any kind of construction I could envision. I almost would have believed the mass of pale figures was engaged in tearing down the splintered endpoint, but their method of doing so was, to put it mildly, impractical.

For some time, in the midst of the other sounds of sea and strain surrounding me, I’d been conscious of another noise, a metallic jingle that seemed to come from all over the place. Only when we were at the large boulder did I understand what I was hearing: the sound of the hundreds, of the thousands, of fishhooks woven into and dangling from the rope that encircled the stone, swinging into one another as the rope shifted. There were hooks, I saw, strung along all the ropes.

You can be sure, throughout the journey Marie had taken me on, Howard’s story had not been far from my thoughts. How could it have been anywhere else, right? But the sight of all those curved bits of metal, some wound tightly into the rope’s fibers, others tied to those fibers by their eyes, a few of sufficient size to be hung on the rope properly — more than the Vivid Trees, or the black ocean, more than Marie, even, this was the detail that made me think, Oh my God. I believe old Howard was telling the truth. Or close enough. As Marie led me around to what I thought of as the front of the boulder, the man who was bound to it came into view, and any doubts that might have remained were swept away by the sight of the rope that crossed him from right hip to left shoulder, secured to him by the fishhooks that dug through the leather apron and worn robes to his flesh. The rope circled the stone behind him a few times, then ran out across the black waves to the end of the barrier.

The strangest thing was, I recognized this man. I’d met him in the woods on the way here, speaking a language I didn’t understand, until Marie chased him off. What had been a matter of an hour, less, for me, had been much, much longer for him. At a glance, you might have mistaken him for my age, a tad older, but subject him to closer inspection, and the number of years piled on him was apparent. This fellow had seen enough time pass that he should have crumbled to dust several times over. His skin was more like parchment paper, and his face was speckled with some kind of barnacle. All the color had been washed from his eyes. They flicked toward me, and a spark of recognition flared in them. He didn’t speak, though; he left that to Dan.

Dan was sitting cross-legged at the man’s feet, his back to him and me. To his right, a slender naked woman, her skin pale as pearl, sat leaning against him. To his left, a pair of toddler boys, their bare bodies equally white, crawled in and out of his lap. His hat and raincoat were gone, his hair tousled, his clothes rumpled, as if he’d slept in them. When he turned to me, the stubble shadowing his face, way later than five o’clock, reinforced my impression that he’d already spent some time in this place. “Abe,” he said. “I was wondering if you’d make it.”

“Here I am.”

Marie lowered herself to the ground next to the woman beside Dan — to Sophie. Dan eased himself from under Sophie, helped the boy who was crawling off him the rest of the way down, and stood, the wince as he did testament to how long he must have been holding that position. He smiled at Sophie. “This is my wife, Sophie.” His hand swept over the boys. “And these young men are Jason and Jonas.” The three of them swiveled their heads to regard me with flat, gold eyes.

“Dan,” I said, “what is all this?”

“Isn’t it obvious? It’s what your friend was telling us about, at the diner. He got some of the details wrong, but as far as the big picture goes, he was pretty much on target.”

“Big — I don’t know what that means.” I inclined my head to the man bound to the rock. “Is this the Fisherman?”

Dan nodded. “He doesn’t say much. All of his energy is focused on…” He pointed to the end of the barrier and its web of ropes.

“Which is what, exactly?”

“I guess you could call it the great-grandfather of all fishing stories.”

“The…” My voice died in my mouth. I must have noticed it during the walk to this spot, observed the odd striations in the stone of which the barrier was composed, even made the comparison to the scales of a titanic reptile. I must have seen the way the end of the barrier curved out and around from the main body the way the head of a snake flares from its neck. Maybe I’d likened the broken rocks ornamenting its crest to the ridges and horns that decorate the skulls of some serpents; maybe I’d judged the crack in which the Fisherman’s rope was lodged to be in the approximate location of an eye, were this headland an actual head. Whatever I’d imagined, I’d done so because this was what you did when you saw something new, especially something large: you found the patterns in it, saw the profiles of giants in the outlines of mountains, found dragons rearing in the clouds overhead. It was a game your mind played with unfamiliar terrain, not an act of recognition, for God’s sake. Of course it explained what all the ropes were for, identified the task towards which all the pale things were bent, but it was ridiculous, it was impossible, you could not have a creature that size, it violated I didn’t know how many laws of nature.

Читать дальше