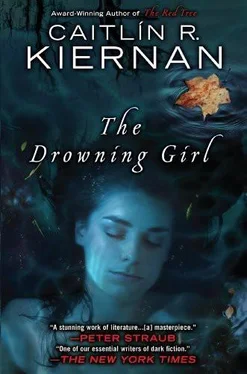

Caitlín Kiernan - The Drowning Girl

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Caitlín Kiernan - The Drowning Girl» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Roc / New American Library, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Drowning Girl

- Автор:

- Издательство:Roc / New American Library

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:978-0-451-46416-3

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Drowning Girl: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Drowning Girl»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Drowning Girl — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Drowning Girl», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

My siren came from the Blackstone River in Massachusetts, a river with the same name as the street that runs past the hospital where my mother died. The Siren of Millville, Perishable Shippen, E. L. Canning, Eva Louise, daughter of Eva May, who walked into Monterey Bay off Moss Landing State Beach, California, when I was only four years old. Who followed a woman named Jacova Angevine into the sea, and who never walked back out again. The deep sea is eternal night, and Jacova Angevine opened that door for E. M. Canning, who obediently stepped through it, along with so many others. She left her illegitimate daughter (like Imp) to her own fate.

“That’s enough rambling prologue, Imp. You’re stalling again. You’re still mired in now , and you’ve sat down to write about then .”

That’s true (and factual). I have sat down to make an end to this. To type the last of my ghost story there is to tell, or, at least, the last of the part from August 2008. One does not find closure, resolution. One is never unhaunted, no matter how much self-help happy-talk purveyors of pop psychology and motivational speaking ladle on. I know that. But at least I will not have to keep coming to the blue room with too many books and continue trying to make sense of my ghost story. I now understand it as well as ever I shall. When I’m done, I’ll show it to Abalyn, and I’ll show it to Dr. Ogilvy, and then I’ll never show it to anyone else, not ever.

A siren came knocking at my door.

It was only a few days after I had lain down in a bathtub of icy water and tried to end an earwig by inhaling myself to oblivion. Abalyn had gone away, and she’d taken all her things with her. I was alone. I was sitting on the sofa, where she sat so often with her laptop. I’d read the same paragraph of a novel several times. I can’t recall what the novel was, and it hardly matters. There was a knock at the door. It wasn’t a loud knocking. It was, I will say, almost a surreptitious knock, almost as if I weren’t meant to hear it, though I was, of course. No one knocks meaning you not to hear, right? No one would ever do such a thing, as a knock at a door or window says “Here I am. Let me in.”

I turned my head and stared at the door. My apartment door is painted the same blue as this room where I type. I waited, and in a few seconds, the surreptitious knock came again. Three raps against the wood. I had no idea who it might be. Abalyn had no reason to come back. Aunt Elaine never comes without calling. Likewise, my few friends all have instructions to always call before visiting. Perhaps, I thought, it was someone from upstairs or someone from downstairs. Perhaps it was Felicia, my landlady, or Gravy, her handyman. On the third surreptitious knock, I called out, “I’m coming.” I stood up and walked to the door.

Before I opened it, I smelled the Blackstone River, exactly as it had smelled the day Abalyn and I drove up there, only to find nothing but a few footprints in the muddy bank. So, I knew who was behind the door. I breathed in silt and murky water and crayfish and carp and snakes and dragonflies, and so I knew precisely who had come calling. I said her name aloud, before I turned the knob.

I said, “Eva.” And then I opened the door. My own Open Door of Night.

She stood on the landing in the same simple red sundress she’d been wearing that scalding day at Wayland Square, and that afternoon at the RISD Museum. She was barefoot, and her toenails were polished a silvery color that reminded me of nacre, which most people call mother-of-pearl. Rosemary Anne had mother-of-pearl earrings when I was a child, but she lost them before she went away to Butler Hospital and I’ve never found them. Eva stood before me, smiling. There was a bundle in her hands, something wrapped in butcher paper and tied up neat with twine.

“Your clothes,” she said, holding out the package. “I had them cleaned.” She didn’t say hello. She offered me the package, and I took it from her.

“I knew you’d come,” I said. “Even if I didn’t know I knew, I knew all the same.”

And she smiled like a shark, or like a barracuda might smile, and she said, “May I come in, India Morgan Phelps?”

I regarded her a moment, and then I said, “That day at the gallery, you told me the time for choice is behind us both. So, why are you bothering to ask?” And I thought of the stories that say vampires and other malevolent spirits have to be invited into your home. (Though hadn’t I invited her once already?)

“I’m only being polite,” she replied.

“But if I say no, you’re not going to leave, are you?”

“No, Imp. We’ve come too far.”

I very almost said, “So remote from the night of first ages.…We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there—there you could look at a thing monstrous and free.” But I didn’t. I didn’t have the nerve, and I didn’t think it would matter. There was no ward to drive her back, not from Joseph Conrad or Herman Melville or Matthew Arnold. Not from any holy book or infernal grimoire. I knew this, as surely as I knew the thing standing on my doorstep was alive and meant to enter, whether I wished it to or not.

But, to tell the truth, I desired nothing more.

“Yeah, you can come in,” I said. “Where are my manners?”

“Well, you weren’t expecting me.”

“Of course I was,” I told her, and she smiled again.

In a notebook, Leonardo da Vinci wrote, “The siren sings so sweetly, she lulls mariners to sleep. She boards ships and murders sleeping mariners.” Translated into English, this is what he wrote. Those who wrote of the fairy Unseelie Court told of the Each-Uisge (ekh-ooshh-kya), the Kelpie, who haunted lakes and bays and rivers in Ireland and Scotland. It rose from the slime and the reeds, a water horse , and any foolish enough to ride were drowned and eaten. Except the liver. The Each-Uisge disdains the liver. I don’t like liver, either.

Imp typed, “You’re drifting again.”

Sailing ships—clippers, dories, schooners, smacks, trawlers, gigantic cargo ships and toxic oil tankers, whaling ships—adrift on treacherous currents and storm winds, and they dash themselves to splinters on jagged headlands.

“Drifting,” Imp typed. “Tiller hard to port. Hold to true north, if you’re not to stray.”

Eva Canning stepped across my threshold.

“Who are hearsed that die on the sea?”

She shut the door behind her, and the latch clicked loudly. She turned the dead bolt, and I found nothing the least bit strange about her doing it. Nothing strange at all about her locking me into my own apartment, with her. I understood she’d not come so far only to be interrupted by intruders. I imagine so many before me have drowned in the depths of her bottle-blue eyes. She’s exactly, exactly, exactly as I remembered her from the July night by the Blackstone River, and from that day at the gallery. Her hair so long and the color of nothing at all, only the color of a place where no light has ever shone.

She turned away from the locked door. She turned towards me. She touched my cheek, and her skin felt like silk against mine. My skin felt like sandpaper compared with hers. This impression was so pronounced that I wanted to pull away and warn her not to cut herself. Her hand had not been fashioned to touch the likes of me. I think of stories I’ve read in books, tales of sharks brushing against swimmers, and how the denticles of sharkskin scrapes bare flesh raw. But here our roles are reversed, if only for this swift assemblage of instants. I am the author of abrasions, or I fear I will be.

But I draw no drop of blood from that silken hand.

“You hurt me,” I say. “You put words in my mind, and I almost died to get them out again.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Drowning Girl»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Drowning Girl» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Drowning Girl» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.