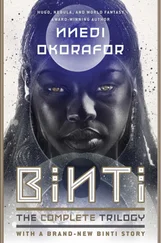

But sometimes a girl is still forced , I thought, thinking of Binta.

“Aro wouldn’t teach me a thing,” she said. “I asked about the Mystic Points and he only laughed at me. I was fine with this but when I asked him about small things like helping the plants grow, keeping ants out of our kitchen, keeping the sand out of our computer, he was always too busy. He’d even place the Eleventh Rite juju on the scalpels when I was not around! It felt… wrong .

“You’re right, Onyesonwu. There should be no secrets between a husband and wife. Aro is full of secrets and he gives no excuse for keeping them. I told him I was leaving. He asked me to stay. He shouted and threatened. I was a woman and he was a man, he said. True. By leaving him, I went against all that I was taught. It was harder than leaving my children.

“He bought me this house. He comes to me often. He’s still my husband. He was the one who described the Lake of the Seven Rivers to me.”

“Oh,” I said.

“He’s always given me inspiration to paint. But when it comes to those deeper things, he tells me nothing.”

“Because you’re a woman?” I asked hopelessly, my shoulder slumping.

“Yes.”

“Please, Ada-m, ” I said. I considered getting on my knees, but then I thought of Mwita’s uncle begging the sorcerer Daib. “Ask him to change his mind. At my Eleventh Rite, you yourself said that I should go see him.”

She looked annoyed. “I was foolish and so is your request,” she said. “Stop making a fool of yourself by going over there. He enjoys saying no.”

I sipped my tea. “Oh,” I said, suddenly realizing. “That fish man near the door. The one that is so old with the intense eyes. That’s Aro, isn’t it?”

“Of course it is,” she said.

Chapter 14

The Storyteller

The man juggled large blue stone balls with one hand. He did it with such ease that I wondered if he was using juju. He is a man, so it’s possible, I thought resentfully. It had been three months since Aro had rejected me that second time. I don’t know how I got through those days. Who knew when my biological father would strike again?

Luyu, Binta, and Diti weren’t so amazed by the juggler. It was a Rest Day. They were more interested in gossip.

“I hear Sihu was betrothed,” Diti said.

“Her parents want to use the bride price to invest in their business,” Luyu said. “Can you imagine being married at twelve?”

“Maybe,” Binta said quietly, looking away.

“I could,” Diti said. “And I wouldn’t mind having a husband who is much older. He would take good care of me as he should.”

“Your husband will be Fanasi,” Luyu said.

Diti rolled her eyes, irritated. Fanasi still wouldn’t speak to her.

Luyu laughed and said, “Just watch and see if I’m not right.”

“I’m not watching for anything,” Diti grumbled.

“ I want to marry as soon as possible,” Luyu said with a sly grin.

“ That’s not a reason to marry,” Diti said.

“Says who?” Luyu asked. “People marry for lesser reasons.”

“I don’t want to marry at all,” Binta mumbled.

Marriage was the last thing on my mind. Plus Ewu children weren’t marriageable. I would be an insult to any family. And Mwita had no family to marry us. On top of all this I questioned what intercourse would be like if we were married. In school we were taught about female anatomy. We focused most on how to deliver a child if a healer was unavailable. We learned ways of preventing conception, though none of us could understand why anyone would want to. We’d learned how a man’s penis worked. But we skipped the section on how a woman was aroused.

I read this chapter on my own and I learned that my Eleventh Rite took more from me than true intimacy. There is no word in Okeke for the flesh cut from me. The medical term, derived from English, was clitoris. It created much of a woman’s pleasure during intercourse. Why in Ani’s name is this removed? I wondered, perplexed. Who could I ask? The healer? She was there the night I was circumcised! I thought about the rich and electrifying feeling that Mwita always conjured up in me with a kiss, just before the pain came. I wondered if I’d been ruined. I didn’t even have to have it done.

I tuned out Luyu and Diti’s talk of marriage and watched the juggler throw his balls in the air, do a somersault, and catch them. I clapped and the juggler smiled at me. I smiled back. When he first saw me, he did a double take and then looked away. Now I was his most valuable audience member.

“The Okeke and the Nuru!” someone announced. I jumped. The woman was very very tall and strongly built. She wore a long white dress that was tight at the top to accentuate her ample bosom. Her voice easily cut through the market’s noise.

“I bring news and stories from the West.” She winked. “For those who wish to know, come back here when the sun sets.” Then she dramatically whirled around and left the market square. She probably made this announcement every half hour.

“Pss, who wants to hear more bad news?” Luyu grumbled. “We’ve had enough with that photographer.”

“I agree,” Diti said. “Goodness. It’s a Rest Day.”

“Nothing can be done about the problems over there, anyway,” Binta said.

That was all that my friends had to say on the matter. They forgot or simply overlooked me, who I was. I’ll just go with Mwita then , I thought.

According to rumor, like the photographer, the storyteller was from the West. My mother didn’t want to go. I understood. She was relaxing in Papa’s arms on the couch. They were playing a game of Warri. As I prepared to leave, I felt a pang of loneliness.

“Will Mwita be there?” my mother asked.

“I hope so,” I said. “He was supposed to be here tonight.”

“Come right home, afterward,” Papa said.

The town square was lit by palm oil lanterns. There were drums set in front of the iroko tree. Few people came. Most were older men. One of the younger men was Mwita. Even in the dim light, I could easily see him. He sat to the far left, leaning against the raffia fence that separated market booths from passersby. No one sat near him. I sat beside him and he put his arm around my waist.

“You were supposed to meet me at my house,” I said.

“I had another engagement,” he said, with a slight smile.

I paused, surprised. Then I said, “I don’t care.”

“You do.”

“I don’t.”

“You think it’s another woman.”

“I don’t care.”

Of course I did.

A man with a shiny bald head sat down behind the drums. His hands produced a soft beat. Everyone stopped talking. “Good evening,” the storyteller said, walking into the lantern light. People clapped. My eyes widened. A crab shell dangled from a chain around her neck. It was small and delicate. Its whiteness shone in the lantern light against her skin. It had to be from one of the Seven Rivers. In Jwahir, it would be priceless.

“I’m a poor woman,” she said, looking out at her small crowd. She pointed to a calabash decorated with orange glass beads. “I got this in exchange for a story when I was in Gadi, an Okeke community beside the Fourth River. I’ve traveled that far, people. But the farther east I have come, the poorer I get. Fewer people want to hear my most potent stories and those are the ones I want to tell.”

She sat down heavily and crossed her thick legs. She adjusted her expansive dress to fall over her knees. “I don’t care for wealth, but please when you leave, put what you can in here, gold, iron, silver, salt chips, as long as it’s worth more than sand,” she said. “Something for something. Am I heard?”

Читать дальше