"The altars of Bel are of gold and rayed like the sun! On them burn the golden fires of the summer lightnings and the smoke of the incense hangs over them like the clouds of the thunderstorm! The Kerubs whose bodies are lions and whose heads are eagle heads, and the Kerubs whose bodies are bulls and whose heads are the heads of men guard the golden altars of Bel, and both are winged with mighty wings! And the altars of Bel are reared upon thews of elephants and are held upon the necks of buijs and the paws of lions!

"He goes by them! He sees the fires of the lightnings sink and the altar shake! In his ears is the sound of worlds crushed by the fist of Bel; of worlds breaking beneath the smiting of Bel!

"Yet he passes!

"For lo! Not even the Might of God may crush the desire of man!"

The voice ceased, it seemed to retreat to those far regions whence it had come. In its withdrawal Kenton sensed finality; knew it would sound no more for him there; that now he was thrown on his own wit and strength; must captain his own way henceforward.

Out from one side of the House of Bel jutted a squared buttress, perpendicular, fifty feet or more wide. It thrust itself into this temple within a temple like the gigantic pier of a bridge. Its top was hidden.

Down its smooth facade darted a broad and angled streak of gold that Kenton for an instant took to be a colossal ornament, a symboling of the darting lightning bolt of Bel. Closer he came to it, following the priest. And now he saw that the golden streak was no ornament. It was a stairway, fashioned to represent the leaping levin but—a stairway. A stepped stairway of sharply angled flights that, clinging to the mighty buttress wall, climbed from the floor of the House of Bel up to—what?

At the foot the priest of Bel faltered; for the first time he looked behind him; seemed half moved to retreat. Then with the same despairing gesture of defiance with which he had turned from the altar, he began to creep cautiously, silently up the angled stairs.

And Kenton, waiting again, until he was but a shadow in the shining mists, followed.

THE TEMPEST had struck. Kenton, climbing, heard thunderings like the clashing of armied shields; clanging of countless cymbals, tintamarre of millions of gongs of brass. Ever louder grew the clangor as he ascended; with it mingled now the diapason of mighty winds, staccato of cataracts of rain.

The stairway climbed the sheer wall of the buttress as a vine a tower. It was not wide—three men might march abreast up it; no more. Up it went, dizzily. Five sharp–angled flights of forty steps, four lesser–angled flights of fifteen steps he trod before he reached its top. Guarding the outer edge was only a thick rope of twisted gold supported by pillars five feet apart.

So high was it that when Kenton neared its end and looked down he saw Bel's house only as a place of golden mists—as though he looked from some high mountain ledge upon a valley whose cloudy coverlet had just been touched by rays of morning sun.

The clinging stairway's last step was a slab some ten feet long and six wide. Upon it a doorway opened—a narrow arched portal barely wide enough for two men to pass within it side by side. The doorway looked out, over the little platform, into the misty space of the inner temple.

The hidden chamber into which it led rested upon the head of the gigantic buttress.

One man might hold that stair end against hundreds. The doorway was closed by a single fold of golden curtains as heavy and metallic as those which had covered the portal of the Moon God's Silver House. Involuntarily he shrank back from parting them—remembering what the parting of those argent hangings had revealed to him.

He mastered that fear; drew a corner of them aside.

He looked into a quadrangular chamber, perhaps thirty feet square, filled with the dancing peacock plumes of the lightnings. He knew it for his goal—Bel's place of pleasance where Kenton's love waited, fettered by dream.

He glimpsed the priest crouched against the further wall, rapt upon a white veiled woman standing, arms stretched wide, beside a deep window close to the chamber's right hand corner. The window was closed by one wide, clear crystal pane on which the rain beat and the wind lashed. With thousands of brushes dipped in little irised flame the lightnings limned the loves of Bel broidered on hangings on the walls.

In the chamber were a table and two stools of gold; a massive, ivoried wooded couch. Beside the couch was a wide bellied brazier and a censer shaped like a great hour glass. From the brazier arose a tall yellow flame. Upon the table were small cakes, saffron colored, in plates of yellow amber and golden flagons filled with wine. Around the walls were little lamps and under each lamp a ewer filled with fragrant oil for their filling.

Kenton waited, motionless. Danger was gathering below him like a storm cloud with Klaneth stirring it in wizard's caldron. Perforce he waited, knowing that he must fathom this dream of Sharane's—must measure the fantasy in which she moved, mind asleep, before he could awaken her. The blue priest had so told him.

To him came her voice:

"Who has seen the beatings of his wings? Who has heard the tramplings of his feet like the sound of many chariots setting forth for battle? What woman has looked into the brightness of his eyes?"

There was a searing flash, a clashing of thunder—within the chamber itself it seemed. When his own sight had cleared he saw Sharane, hands over eyes, groping from the window.

And in front of the window stood a shape, looming gigantic against the nickering radiance, and helmed and bucklered all in blazing gold—a god–like shape!

Bel–Merodach himself who had leaped there from his steeds of storm and still streaming with his lightnings!

So Kenton for one awed instant thought—then knew it to be the Priest of Bel in the stolen garments of his god.

The white figure, that was Sharane, slowly drew hands from eyes; as slowly let them fall, eyes upon that shining form. Half she dropped to her knees, then raised herself proudly; she searched the partly hidden face with her wide, green dreaming eyes.

"Bel!" she whispered, and again: "Lord Bel!"

The priest spoke: "O beautiful one—for whom await you?"

She answered: "For whom but thee, Lord of the Lightnings!"

"But why await you—me?" the priest asked, nor took step toward her. Kenton, poised to leap and strike, drew back at the question. What was in the mind of the Priest of Bel that he thus temporized?

Sharane spoke, perplexed, half–shamed:

"This is thy house, Bel. Should there not be a woman here to await thee? I—I am a king's daughter. And I have long awaited thee!"

The priest said: "You are fair!" His eyes burned upon her—"Yes—many men must have found you fair. Yet I—am a god!"

"I was fairest among the princesses of Babylon. Who but the fairest should wait for thee in thy house? I am fairest of all—" So Sharane, all tranced passion.

Again the priest spoke:

"Princess, how has it been with those men who thought you fair? Say—did not your beauty slay them like swift, sweet poison?"

"Have I thought of men?" she asked, tremulously.

He answered, sternly. "Yet many men must have thought of you—king's daughter. And poison, be it swift and sweet, must still bear pain. I am—a god! Yet I know that!"

There was a silence; abruptly he asked: "How have you awaited me?"

She said: "I have kept the lamps filled with oil; I have prepared cakes for thee and set out the wine. I have been handmaiden to thee."

The priest said: "Many women have done all this—for men, king's daughter—I am a god!"

She murmured: "I am most beautiful. The princes and the kings have desired me. See—O Great One!"

Читать дальше

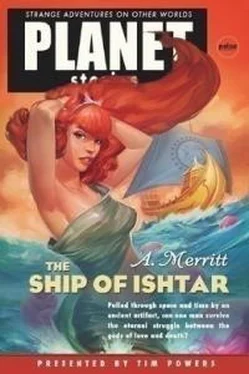

![Абрахам Меррит - Лунный бассейн [Лунная заводь]](/books/20623/abraham-merrit-lunnyj-bassejn-lunnaya-zavod-thumb.webp)