Brian McClellan

SINS OF EMPIRE

2017

For Marlene Napalo,

high school English,

for reading and reviewing my early derivative garbage full of dwarves, elves, and dragons, even though I’m sure you had far better things to do over Christmas break.

And for William Prueter,

high school Latin,

for teaching me to think outside the box and work hard. And because I know winding up at the front of a fantasy novel will irritate you.

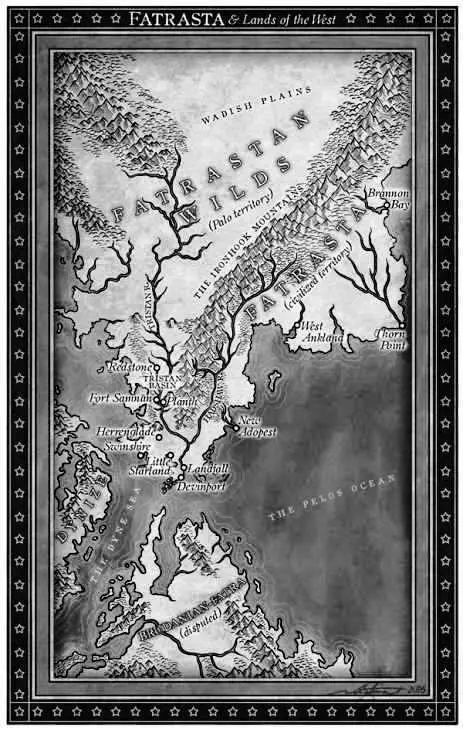

Privileged Robson paused with one foot on the muddy highway and the other on the step of his carriage, his hawkish nose pointed into the hot wind of the Fatrastan countryside. The air was humid and rank, and the smell of distant city smokestacks clung to the insides of his nostrils. Onlookers, he considered, might comment to one another that he looked like a hound testing the air – though only a fool would compare a Privileged sorcerer to a lowly dog anywhere within earshot – and they wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

Privileged sorcery was tuned to the elements and the Else, giving Robson and any of his brother or sister Privileged a deep and unrivaled understanding of the world. Such an understanding, a sixth sense, provided him an invaluable advantage in any number of situations. But in this particular case, it gave Robson nothing more than a vague hint of unease, a cloudy premonition that caused a tingling sensation in his fingertips.

He remained poised on the carriage step for almost a full minute before finally lowering himself to the ground.

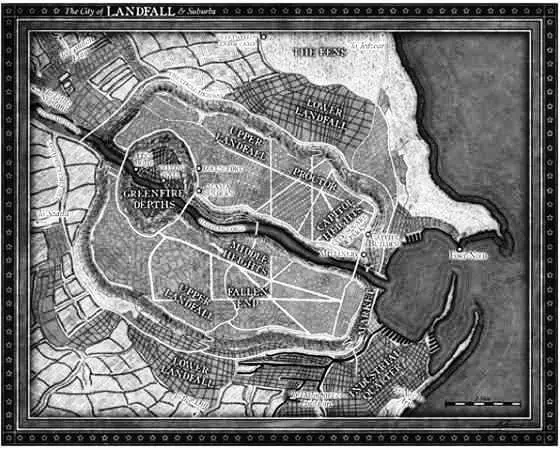

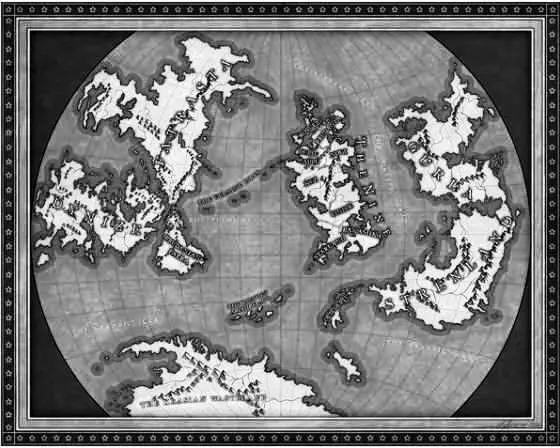

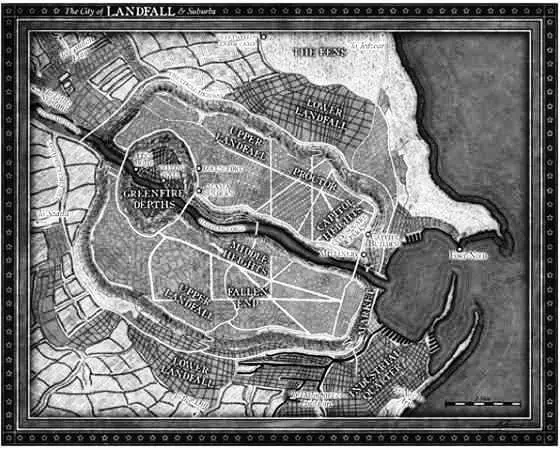

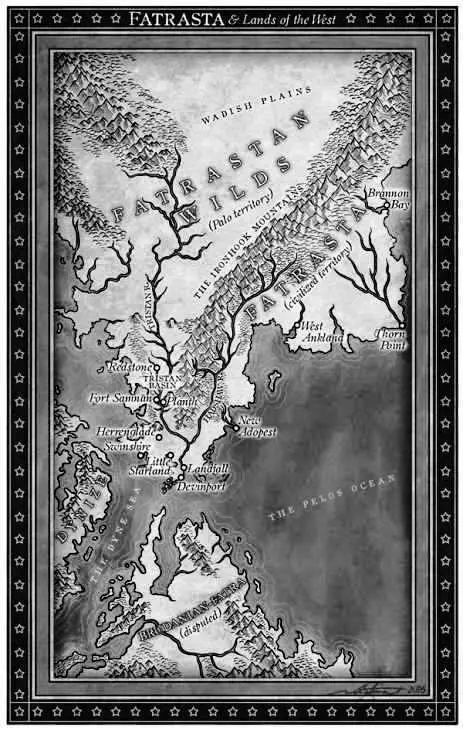

The countryside was empty, floodplains and farmland rolling toward the horizon to the south and west. A salty wind blew off the ocean to the east, and to the north the Fatrastan capital of Landfall sat perched atop a mighty, two-hundred-foot limestone plateau. The city was less than two miles away, practically within spitting distance, and the presence of the Lady Chancellor’s secret police meant that it was very unlikely that any threat was approaching from that direction.

Robson remained beside his carriage, pulling on his gloves and flexing his fingers as he tested his access to the Else. He could feel the usual crackle and spark of sorcery just out of reach, waiting to be tamed, and allowed a small smile at the comfort it brought him. Perhaps he was being foolish. The only thing capable of challenging a Privileged was a powder mage, and there were none of those in Landfall. What else could possibly cause such disquiet?

He scanned the horizon a second and third time, reaching out with his senses. There was nothing out there but a few farmers and the usual highway traffic passing along on the other side of his carriage. He tugged at the Else with a twitch of his middle finger, pulling on the invisible thread until he’d brought enough power into this world to create a shield of hardened air around his body.

One could never be too careful.

“I’ll just be a moment, Thom,” he said to his driver, who was already nodding off in the box.

Robson’s boots squelched as he followed a muddy track away from the highway and toward a cluster of dirty tents. A work camp had been set up a few hundred yards away from the road in the center of a trampled cotton field, occupying the top of a small rise, and a small army of laborers hauled soil from a pit at the center of the camp.

Robson’s unease continued to grow as he approached the camp, but he pushed it aside, forcing a cold smile on his face as an older man left the ring of tents and came out to greet him.

“Privileged Robson,” the man said, bowing several times before offering his hand. “My name is Cressel. Professor Cressel. I’m the head of the excavation. Thank you so much for coming on such short notice.”

Robson shook Cressel’s hand, noting the way the professor flinched when he touched the embroidered fabric of Robson’s gloves. Cressel was a thin man, stooped from years of bending over books, square spectacles perched on the tip of his nose and only a wisp of gray hair remaining on his head. Over sixty years old, he was almost twenty years Robson’s senior and a respected faculty member at Landfall University. Robson practically towered over him.

Cressel snatched his hand back as soon as he was able, clenching and unclenching his fingers as he looked pensively toward the highway. He was, from all appearances, an awfully flighty man.

“I was told it was important,” Robson said.

Cressel stared at him for several moments. “Oh. Yes! Yes, it’s very important. At least, I think so.”

“You think so? I’m having supper with the Lady Chancellor herself in two hours and you think this is important?”

A bead of sweat appeared on Cressel’s forehead. “I’m so sorry, Privileged. I didn’t know, I…”

“I’m already here,” Robson said, cutting off the old professor. “Just get to the point.”

As they drew closer to the camp Robson noted a dozen or so guards, carrying muskets and truncheons, forming a loose cordon around the perimeter. There were more guards inside, distinguished by the yellow jackets they wore, overlooking the laborers.

Robson didn’t entirely approve of work camps. The laborers tended to be unreliable, slow, and weak from malnourishment, but Fatrasta was a frontier city and received more than its fair share of criminals and convicts shipped over from the Nine. Lady Chancellor Lindet had long ago decided the only thing to do with them was let them earn their freedom in the camps. It gave the city enough labor for the dozens of public works projects, and to lend out to private organizations including, in this case, Landfall University.

“Do you know what we’re doing here?” Cressel asked.

“Digging up another one of those Dynize relics, I heard.” The damned things were all over the place, ancient testaments to a bygone civilization that had retreated from this continent well before anyone from the Nine actually arrived. They jutted from the center of parks, provided foundations for buildings, and, if some rumors were to be believed, there was an entire city’s worth of stone construction buried beneath the floodplains that surrounded Landfall. Some of the artifacts still retained traces of ancient sorcery, making them of special interest to scholars and Privileged.

“Right. Quite right. The point,” Cressel said, wringing his hands. “The point, Privileged Robson, is that we’ve had six workers go mad since we reached the forty-foot mark of the artifact.”

Robson tore his mind away from the logistics of the labor camp and glanced at Cressel. “Mad, you say?”

“Stark, raving mad,” Cressel confirmed.

“Show me the artifact.”

Cressel led him toward the center of the camp, where they came upon an immense pit in the ground. It was about twenty yards across and nearly as deep, and at its center was an eight-foot-squared obelisk surrounded by scaffolding. Beneath a flaking coat of mud, the obelisk was made of smooth, light gray limestone carved, no doubt, from the quarry at the center of the Landfall Plateau. Robson recognized the large letters on its side as Old Dynize, not an uncommon sight on the ruins that dotted the city.

Читать дальше