Yet Orso was quite alert. He kept looking from face to face, thinking. This room contained some of the most powerful men in the city — and many of them were founder lineage. If anyone acted surprised to see him alive — well. That would be a helpful indication.

Ofelia cleared her throat. “There is no recorded natural occurrence of scriving blackouts,” she said. “Not like a typhoon or some such, anyways — neither in our history, nor that of the Occidentals. So, why don’t we cut to the chase, and simply ask — was this the product of something we did here, in Tevanne?”

The room swelled up with muttering.

“Are you accusing another merchant house of this act, Founder?” demanded a Morsini representative.

“I accuse no one,” said Ofelia, “for I understand nothing. Could it not have been an accidental effect of some research endeavor?”

The muttering grew louder. “Ridiculous,” someone said.

“Preposterous.”

“Outrageous.”

“If Dandolo Chartered is willing to make such a supposition,” said one of the Michiel deputies, “perhaps the Dandolo hypatus can provide us with some supporting research?”

All eyes turned to look at Orso.

Great , he thought.

He cleared his throat and stood. “I must slightly correct my founder’s testimony,” he said. “There is, in hierophantic history, one obscure legend in which the phenomenon we witnessed possibly appears — the Battle of Armiedes.” He coolly looked around at the gathered crowd. Come on, you bastard , he thought. Break for me. Show yourself. “Such methodologies remain beyond the abilities of Tevanne, of course,” he said. “But if we trust our histories, then it is possible.”

One of the Morsinis sighed, exasperated. “More hierophants, more magicians! What more could we expect from a disciple of Tribuno Candiano?”

The room went silent at that. Everyone stared at the Morsini representative, who slowly grew aware that he had greatly overstepped.

“I, ah, apologize,” he said. He turned toward a part of the room that had hitherto remained quiet. “I misspoke, sirs.”

Everyone slowly turned to look at the portion of the room dominated by Company Candiano representatives. There were far fewer of them than the other houses. Sitting in the founder’s seat was a young man of about thirty, pale and clean-shaven, wearing dark-green robes and an ornate flat cap trimmed with a large emerald. He was an oddity in many ways: for one, he was about a third of the age of the other three founders — and he was not, as everyone knew, an actual founder, or indeed a blood relation to the Candiano family at all.

Orso narrowed his eyes at the young man. For though Orso hated many people in Tevanne, he especially loathed Tomas Ziani, the chief officer of Company Candiano.

Tomas Ziani cleared his throat and stood. “You did not misspeak, sir,” he said. “My predecessor, Tribuno Candiano, brought great ruin to our noble house with his Occidental fascinations.”

Our noble house? thought Orso. You married into it, you little shit!

Tomas nodded at Orso. “An experience that the Dandolo hypatus, of course, is keenly aware of.”

Orso gave him the thinnest of smiles, bowed, and sat.

“It is, of course, preposterous to imagine that any Tevanni merchant house is capable of reproducing any hierophantic effects,” said Tomas Ziani, “let alone one that could have accomplished the blackouts, to say nothing of the moral implications. But I regret to say that Founder Dandolo has not truly cut to the quick of the question — what I think we all want to know is, if we want to find out if any merchant house is behind the blackouts…how shall we institute this authority? What body shall have this oversight? And who shall make up this body?”

The room practically exploded with discontented mutterings.

And with that , Orso thought with a sigh, young Tomas delivers the killing blow to this idiot meeting. For this notion was heresy in Tevanne — the idea of some kind of municipal or governmental authority that could inspect the business of the merchant houses? They would genuinely rather fail and die than submit to that.

Ofelia sighed. A handful of tiny, white moths flitted around her head. “What a waste of time,” she said softly, waving them away.

Orso glanced at Tomas, and found, to his surprise, that the young man was watching him. Specifically, he was looking at Orso’s scarf — very, very hard.

“Maybe not entirely,” he said.

When the meeting closed, Orso and Ofelia held a brief conference in the cloisters. “To confirm,” she said quietly. “You do not think this is sabotage?”

“No, Founder,” he said.

“Why are you so certain?”

Because I have a grubby thief who says she saw it happen , he thought. But he said, “If it was sabotage, they could have done a hell of a better job. Why target the Commons? Why only glancingly affect the campos?”

Ofelia Dandolo nodded.

“Is there a… reason to suspect sabotage, Founder?” he asked.

She gave him a piercing look. “Let’s just say,” she said reluctantly, “that your recent work on light could attract…attention.”

This was interesting to him. Orso had been fooling around with scrived lights for decades, but it was only at Dandolo Chartered, with its superior lexicon architecture, that he’d started trying to engineer the reverse: scriving something so it absorbed light, rather than emitting it, producing a halo of perpetual shadow, even in the day.

So the suggestion that Ofelia Dandolo might worry about other houses fearing this technology…that was curious.

What exactly , he wondered, is she planning to veil in shadow?

“As in all things,” she said, “I expect your secrecy, Orso. But especially there.”

“Certainly, Founder.”

“Now…if you will excuse me, I’ve a meeting shortly.”

“I as well,” he said. “Good day, Founder.”

He watched her go, then turned and swept out to the hallways around the council building, where the legions of attendants and administrators and servants hovered to assist the throngs of great and noble men within. Among them was Berenice, yawning and rubbing her puffy eyes. “Just four hours?” she said. “That was quick, sir.”

“Was it,” said Orso, rushing past her. He walked through the crowd of people dressed in white and yellow — Dandolo Chartered colors — and moved on to the red and blue crowd — Morsini House — and then the purple and gold crowd — which was, of course, Michiel Body Corporate.

“Ah,” said Berenice. “Where are we going, sir?”

“You are going somewhere to sleep,” said Orso. “You’ll need it tonight.”

“And when will you sleep, sir?”

“When do I ever sleep, Berenice?”

“Ah. I see, sir.”

He stopped at the crowd of people dressed in dark green and black — Company Candiano colors. This crowd was much smaller, and much less refined. The effects of the Candiano bankruptcy still lingered, it seemed.

“Uh…what would you be planning to do here, sir?” asked Berenice with a touch of anxiety.

Читать дальше

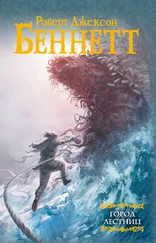

![Роберт Беннет - Город чудес [litres]](/books/405553/robert-bennet-gorod-chudes-litres-thumb.webp)