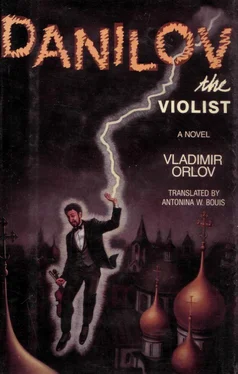

The black void was replaced by crimson. In the distance fiery white peaks, which had not been there before, exploded and collapsed. The crowd of wild creatures was now swirled and beaten into a lump and mashed with cruel, hooked fingers by an element hostile to them. Then there were more explosions, stronger and more horrible than before. Now Danilov was shaken. He realized a catastrophe was imminent: the end of everything he could see or perhaps to everything in which he existed. The creatures and phantoms were dying, vanishing, the violet blisters were swelling up, everything was turning to dust, and once again Danilov saw the floating spirals, disks, galaxies, and planets. There motion grew somnolent, as if everything were turning to ice. Danilov was not cold, but he felt icy and doomed. The blackness and stillness took him into itself.

Then he woke up. For how many minutes or centuries he had not been alive, he did not know. He was in emptiness. To the left there seemed to be the glimmer of dawn. "What's that lying over there?" Actually, he saw clearly what it was: the shoemaker's leather apron. Danilov wanted to walk or float over to it, but he could not twitch or quiver a single muscle. The apron vanished.

"Did they forget to take it away out of carelessness," thought Danilov, "or did they leave it for a reason? But what meaning is there to that apron?" What could he say in response? Nothing. He had to consider it a miracle that he still existed. He tried to marshal his willpower again by keeping track of time, by re-creating music inside himself -- any that he could remember -- and to think in a way that was comforting for him. As Danilov strained, something caught him up and spun him around -- it was like being inside a tornado funnel -- and lifted him high. This was the feeling he had been trying to avoid. He felt eternity. The sensation was instantaneous and piercing. Danilov imagined his hair had turned white.

Danilov was flung down. Then he heard something scraping and striking metal.

And the blackness took Danilov in again and seemed to dissolve him.

35

Danilov lay on a bed with a metal grid, the kind found in hotel rooms in smallish cities. The mattress was thin, and Danilov could feel with his ribs the grid, which had been stretched by long years of use. The bed actually now resembled a hammock. As for the bed linens, they were freshly laundered, clean-smelling, with the rubber-stamped inventory markings in the right places. Danilov lay there in a pair of blue pajamas. Next to the bed stood a walnut wardrobe, where perhaps Danilov's clothes hung, including his coat and nutria hat. On previous occasions he had been assigned much nicer accommodations, sometimes even suites with palatial alcoves and silver-framed mirrors and ceiling paintings by Boucher.

Smarting from the insult, Danilov pulled the rough blanket over his head. And awoke completely. How could he be huffy? What was his problem? Why be a fool? So it wasn't Versailles or Sans Souci or the Houston Hilton -- after all, this was following the Well of Anticipation. He was lucky to be alive and have bed linens, which even though worn, were clean and ironed. And on the night table next to the radio was a carafe containing some liquid.

Danilov was encouraged. He sat up, pulled the carafe over, and drank straight from it. The liquid was lukewarm. Nevertheless, Danilov drank half of it. That made him hungry. And there was something encouraging about even that bodily need. It meant he was alive and wanted to live. The menu for breakfast (call it breakfast, Danilov decided) would be communicated to him either by interior signals or sent typed on a piece of paper. Here Danilov considered himself clever: The dishes listed would give him an inkling of the degree of trouble he was in. How were they planning to feed him? Like a prisoner? A convict on death row? A guest? Someone out of favor? Or what?

Danilov arose and found worn slippers under the bed. At the sink, he brushed his teeth with a rough brush and combed his hair. And reached out to discover his fate.

There were many dishes, but they all came from railroad station cafes. "Have they got me confused with Karmadon?" he thought. Maybe this was a new fashionable cuisine here?

Danilov decided to eat first and guess later, especially since there was boiled chicken on the menu. On previous occasions when he had come from Earth on a summons, Danilov himself had ordered chicken wrapped in Sport. Now the chicken arrived cold and lean, but Danilov gladly swallowed it and chewed on the bones. Danilov demanded paper napkins; napkins appeared. He asked for a toothpick, and they sent one down.

There was no doubt that yesterday (yes, yesterday!) in the Well of Anticipation, besides everything else, they had more in mind than just scaring him or offering him puzzles. The investigators were indubitably interested in his reactions to the visions and cataclysms. And finally, at the revelation of eternity. (When Danilov had seen his face in the mirror over the sink, he was amazed to find his hair had not turned white.) Of course, when he woke up he had realized that the sensation of eternity had left him. The abyss was forgotten. They had removed the instant of enlightenment. He vaguely recalled that his future had been revealed, too. So what, then? Had they dunked him into eternity by accident? Had they given Danilov excess information by mistake, and then, realizing their error, wiped it from his memory with a wet rag to make sure he found no loophole in the future? Or had they simply needed his instantaneous reaction? And no more?

Now Danilov strained his memory, hoping to resurrect even a grain of information. But in vain. By now his responses had been studied and were in the files.

"Let them!" Danilov thought desperately. "Let them! What more can they learn about me? Why did they waste their time and energy?" And a lot of effort and energy had been expended in the Well of Anticipation. All those crashes, worlds, galaxies, all that confusion of the essences of things and phenomena! They had shown him a lot of nonsense and bizarre things that had never existed in real life. For instance, the Cossack with the sleeping child behind him throwing a corpse into the abyss was borrowed from Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol. He wondered if the investigators had actually read Terrible Revenge, or whether some information on it (perhaps distorted: the Carpathian Mountains was a rather rough estimate) had gotten into their files in some oblique way. Of course, it didn't really matter. What mattered was that the investigators had tried to affect him in much the same way Karmadon had. What were they preparing for him now? "Hah!" Danilov dismissed the idea.

He decided to order a wall clock from the Serdovsk factory, and pushed his luck by asking for a cuckoo clock. The clock showed it was lunchtime. Pages of a menu descended into his hands, and they listed dishes from a restaurant car. "When did this insane vogue begin?" Danilov asked, worried. In the past he had been fed turtle soup and had even allowed himself to turn down oysters in wine...

Danilov sighed. Really, were they confusing him with Karmadon, or reminding him of the duel? Where was Karmadon now? Punished, or had he risen up, straightened his jaw, been promoted, and was now sitting next to Danilov's observers? Danilov thought that if the summons had been occasioned by Karmadon and the duel, his case might not be so hopeless.

By now the dishes were on the table. "Don't they have any beer? Not even one botde?" Danilov was incensed but he still pleaded. Apparently it wasn't a question of the kitchen's refrigerators, though -- the client did not have a right to beer.

Soon Danilov was thinking that being dressed in pajamas was not hotel-like but prisonlike, pathetic, as if he had given up and was prepared to position his head precisely on the block to make things easier for the executioner. No, he had to take off the pajamas immediately and go somewhere. Not without a twinge of fear, Danilov went over to the wardrobe. Before, he had been certain that his winter clothes were in there. But what if they had been taken away, leaving him only the pajamas? Danilov pulled the door handle aggressively, as if he had been robbed. No, they had left his Moscow winter clothing. Danilov was ashamed of his thoughts; it was a good thing he didn't pull off the door in his anger. After some hesitation, he asked for immediate delivery of a decent suit for going about in society. They sent the suit. When he put it on he realized that it was well made. He stood there, touched. Outer-appearance services obviously was treating him more kindly than nutrition services. Maybe there were reasons for that? Or did the services exist independently? Why bother guessing?

Читать дальше