"That is all very cruel."

"So be it. But it's also honest... and it was cruel to me as well. I liked Misha... I couldn't even go to the funeral... I didn't have the strength..."

"But you're alive. And he's dead."

Zemsky loomed over Danilov. Is this the Zemsky who just yesterday reeled in confusion with the knife in the buffet? No. This was an oracle, who knew that his prophecies would come to pass. Triumph glowed in Zemsky's eyes. Nikolai Borisovich Zemsky towered above all humanity.

Danilov could no longer sit beneath Zemsky, and he stood up. His movement was harsh, a protest. Nikolai Borisovich noticed it, came to his senses, and spoke more softly.

"The real artist is lonely. I'm lonely. And so are you."

"I'm lonely?" Danilov was amazed.

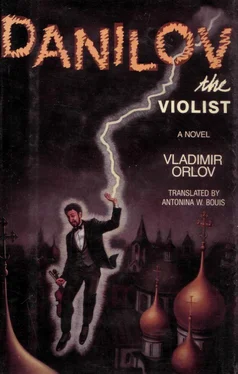

"You're lonely," Zemsky said with a nod. "Let me tell you: You can become a great musician. In the old meaning of the word. I've been listening to you for seven years, maybe more. You're playing better and better. And since you lost your Albani, you're playing even more colorfully on your plain instrument. Others are willing to pay almost any price just for a small success, for a tiny bit of fame... Misha Korenev? He was willing to sell his soul to the devil in moments of desperation... He tried to play the Paganini, it didn't work, and he thought: What if Paganini really had made a pact with the devil? ..."

"It never happened!" Danilov said.

"Why didn't it!" Nikolai Borisovich exclaimed in a high-pitched, nervous voice. "Misha had moments when he wanted to believe in the possibility of that deal! Why talk about Misha? I have those moments, too..."

"Are you serious?" Danilov asked.

"I couldn't be more serious! I get so depressed sometimes that I, Nikolai Borisovich Zemsky, am ready to fall to my knees before anyone -- supernatural being or alien from an advanced civilization, anyone -- fall to my knees and beg him to make me all-powerful, at least in art, and famous, and he can demand any payment in return he wants!"

Zemsky fell on his knees before Danilov.

"I'll sign anything, the most horrible document, in blood if necessary," Nikolai Borisovich exclaimed. "If you need my soul, then take it; if you want my life, take it; if I have to suffer later or perform some deed, fine, I agree! Just satisfy my desire!"

"Get up, Nikolai Borisovich. Why are you on your knees before me?"

"Who else then?" Zemsky asked.

"Get up immediately, Nikolai Borisovich," Danilov said dryly. "Really, it's rather unpleasant."

Nikolai Borisovich had fallen to his knees, but he rose with difficulty, as if his lumbago were acting up. A broken old man, he moved to the armchair, and Danilov saw that the fire had gone out of his eyes. There was no hope.

After a silence, Zemsky asked: "Your friend from Irkutsk, he isn't coming around anymore?"

"I'm not sure," Danilov said, "but I don't think that falling to your knees before him would be wise."

"Maybe," Zemsky whispered. "Maybe. I was just... just in case -- "

"And why all of a sudden?" Danilov asked. "Why do you need someone's help? What's the matter -- aren't you sure of silencism?"

"I'm sure! I'm sure!" Nikolai Borisovich yelled, "but who will understand my silencism now? No one. Who will learn about my works a hundred years from now? No one. I'll drop dead and the Pioneers* will haul off my papers to the recycling plant: Who needs the stuff of somebody named Zemsky? In order for there to be any interest in my theories and compositions, a hundred years from now, I have to become famous now. Now! And for that I am prepared to sign anything. And in blood!"

"I can't be of any help to you," Danilov said.

"Is that so?"

"Nikolai Borisovich, you are looking at me strangely. Are you trying to frighten me the way you frightened Misha Korenev?"

"If you are what you say you are -- "

"I don't say I'm anyone," Danilov said. "However, I am definitely getting the impression that you are taking me for someone else. Who?"

"It could be anyone -- "

"You," Danilov said angrily, "apparently have convinced yourself of some childish nonsense... It's ridiculous and unpleasant..."

"Forgive me, Volodya!" Zemsky said, speaking fast. "It's all a joke... but, as you know, not everyone likes my jokes... Forgive me... Forget what I said... It's time to get to the theater. I'll give you a cognac for the road. And I'll have some homemade wine."

Nikolai Borisovich filled Danilov's shot glass and then headed into the next room. He returned with a large chalice, made, as Danilov saw, from a skull and circled, on top and bottom, with bands of silver. The silver was engraved. The wine in the chalice was cherry-colored and somewhat transparent. "What a lunatic!" Danilov thought.

"It's all a joke, Volodya! Maybe I still believe in my own strength!"

Here Nikolai Borisovich burst out laughing, opened the ring on the middle finger of his left hand, and poured a red powder into the cup. This made the cherry liquid boil and bubble, and blue-gray steam arose from it. Nikolai Borisovich hoisted the chalice and emptied it like a water glass. Danilov did not feel like having cognac, but he drank it now. "Mysticism of some sort," thought Danilov.

In the entry way, Danilov said to Zemsky: "You can keep your blood-red wine, that's your business. However, you curtailed Korenev's life needlessly."

"Maybe I did and maybe I didn't!" said Zemsky with a laugh. The cherry liquid had made him high. He seemed to be bursting with joy. With his broad belly he pushed Danilov against the entry wall and deafened him:

"You, Danilov, don't show off! What do you know? Nothing! Now, Misha took away a mystery with him. Figure it out. That would be something!"

As he headed for the elevator, Danilov nevertheless turned to give Zemsky a stiff little bow. Zemsky slammed the door behind him.

26

At the theater Danilov learned that the fireproof lockers for the instruments had come. Turukanov played a "Gloria" on his trumpet in honor of the administration and the union. Danilov received the key to his locker, drove in a nail for his tuxedo hanger, and thought how good it would have been to put his Albani in there, too. He sat on the floor next to his locker. The past few days had been so busy he had almost forgotten the Albani. And now he felt sick. As if he had just discovered the loss.

"Nice locker, eh?" Zemsky asked.

"It's nice," Danilov agreed.

"Nice ... I'm thinking of lining mine with cloth ... black... The union could, if they wanted to...."

"They could..."

"That Turukanov is persistent," Zemsky said, referring to the cellist, their local leader. "He should be a store director or be in charge of supplies at a factory. But this time that pig is fine!"

Danilov also considered Turukanov a real pig, but for getting the lockers he deserved a vote of thanks.

"I hear you're going to do a solo performance soon. At the Searchlight Factory Club."

"I am?"

"You are. With a youth orchestra. You're going to perform a symphony by some novice? ..."

"How do you know?"

"I know," Zemsky said. "Aren't you taking a risk at your age? Well, why not? ... The bigger they are, the harder they fall.... Aren't you afraid?"

"I'm afraid," Danilov said and turned away from Zemsky.

"What does the Searchlight Factory Club have to do with this?" thought Danilov. Of course, he knew that Zemsky did free-lance work with factory opera companies, where he actually moved his bow across the strings, and obtained loud noises that could be heard back in the accounting offices. That's where Zemsky must have gotten information about the Searchlight Factory Club.

Pereslegin called from a phone booth. Danilov could hear streetcars running past. Pereslegin said that everything was moving along, Danilov had to meet tomorrow with Yuri Chudetsky, the conductor of the youth orchestra. The orchestra was a good one, with a full complement, all professionals; Danilov didn't need to worry. And if Danilov hadn't changed his mind, of course, the performance would be in three weeks or so.

Читать дальше