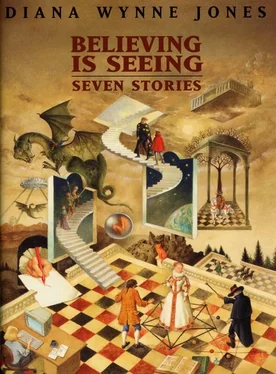

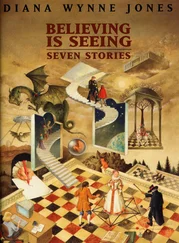

DIANA WYNNE JONES

Believing Is Seeing

Seven stories

These stories were written at intervals over a long period, and it so happened that each time I had written one of them, someone asked me for a story for a collection. I began to feel positively precognitive.

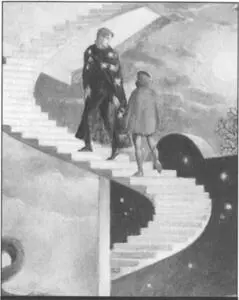

The trouble is that the collection didn’t always match the story. “The Sage of Theare” started because I remembered, or thought I remembered, a story by Borges being read on the radio, in which a scholar arduously tracked down a learned man but never quite found him. I have never actually found that story either. If it exists, it behaves like its own plot. But years after I thought I remembered hearing it, I started having dreams about it—strange circular dreams in a strange city where gods took a hand—and the dream person never found the wise man he was looking for. In order to exorcise the dreams, I wrote the story. I was writing Chrestomanci books at the time, so the story fairly naturally included Chrestomanci, too. While I was finishing it, Susan Schwartz asked me for something for a collection called Hecate’s Cauldron, and with some doubts, I sent it to her. She used it, and to my dismay, it stuck out like a sore thumb. All the other stories were very female. Chrestomanci strides among them like a grasshopper in a beehive. His effect on the gods in the story is rather the same, too.

“The Master” was another dream, or maybe a nightmare, which I dreamed more than once and had again to exorcise by writing it down. I know it is really part of the complex of ideas out of which Fire and Hemlock got written, but I couldn’t explain how. It is, of course, about precognition. At that time, I was quite worried about the way most of my books came true at me after I had written them, but I am glad to say that the events in “The Master” have (so far) not happened to me.

One rainy afternoon quite a long time later I sat down and wrote “The Girl Who Loved the Sun.” I had been thinking about all those Greek stories where women get turned into plants and animals, and I kept wondering how and why: how it felt to the person it happened to and why they let it happen. It seemed to me that nothing that radical could happen to someone without their personal consent, and I wondered why one might consent. When I had done the first draft, I had two phone calls. The first was from my sister, who wanted to tell me she had been writing poems about women who were turned into plants and animals and asking much the same questions as I had (my sister and I seem to share trains of thought quite often), and the second was someone wanting a story about unhappy love. I sent this story, as doubtfully as I had earlier sent “The Sage of Theare,” because I was not sure it quite counted. But they said it did. You must see what you think.

Peculiarly, I do not remember why I wrote “Enna Hittims,” but I presume I was sick in bed and feeling bored. And when Greenwillow asked me for a new story for this collection, it was ready and waiting.

Much earlier than all of these, while I was thinking out the multiplicity of alternate worlds that occur in The Lives of Christopher Chant, I wrote “Dragon Reserve, Home Eight” almost by way of clarifying things. At that time, though, I was thinking of the worlds as rather like a wad of different colored paper handkerchiefs. If you were to take that wad and crumple it in one hand, each color would be separate, but wrapped in with the others. And I was also thinking of an enchanter’s gifts rather more as inborn psychic talents. As so often happens, when I came to write the actual book a good four years later, everything turned out differently, and probably no one would realize this story had anything to do with it unless I told them. Again, I had just done a rather rough and unsatisfactory first draft when Robin McKinley asked me for a fantasy story. I sent this one, but she refused it on the grounds that it was not fantasy. This struck me as fair and reasonable, even though I knew it was going to be fantasy later.

I asked myself for a story with “What the Cat Told Me.” When I wrote it, I was suffering cat deprivation. I was brought up with cats and didn’t have one at that time (this was four years ago, just before someone suddenly arrived and organized me a cat, so this one came true in a way). I love the exacting self-centeredness of cats. The story is about that. Then I was asked to compile a collection of fantasy stories, and I put this one in among the original selection, which I knew was going to be far too long. I mean, what can one leave out of a fantasy collection? My idea was to leave my own story out. But when it came to cutting the list down to publishable size, the editors, to my great surprise, insisted that this one stay in. I was glad. It was fun to write.

It was even more fun to write “nad and Dan adn Quaffy.” This one is a loving send-up of a well-known author whose writing I admire and read so avidly that I’m sure I know where a lot of it comes from. The idea for it came to me as I typed nad for and for the hundredth time, changed it, found it was now adn, reached for my coffee in frustration, and idly realized—among other things—that this other writer did this, too. Typos are a great inspiration. Depending on which side you hit the wrong key, coffee can be either xiddaw or voggrr , both of which are obviously alien substances that induce a state of altered consciousness. And yet again, when I was halfway through it, giggling as I wrote, I was asked for a story about computers.

And there you are: believing is seeing.

Diana Wynne Jones

Bristol, 1999

There was a world called Theare in which Heaven was very well organized. Everything was so precisely worked out that every god knew his or her exact duties, correct prayers, right times for business, utterly exact character, and unmistakable place above or below other gods. This was the case from Great Zond, the king of the gods, through every god, godlet, deity, minor deity, and numen, down to the most immaterial nymph. Even the invisible dragons that lived in the rivers had their invisible lines of demarcation. The universe ran like clockwork. Mankind was not always so regular, but the gods were there to set him right. It had been like this for centuries.

So it was a breach in the very nature of things when, in the middle of the yearly Festival of Water, at which only watery deities were entitled to be present, Great Zond looked up to see Imperion, god of the sun, storming toward him down the halls of Heaven.

“Go away!” cried Zond, aghast.

But Imperion swept on, causing the watery deities gathered there to steam and hiss, and arrived in a wave of heat and warm water at the foot of Zond’s high throne.

“Father!” Imperion cried urgently.

A high god like Imperion was entitled to call Zond Father. Zond did not recall whether or not he was actually Imperion’s father. The origins of the gods were not quite so orderly as their present existence. But Zond knew that, son of his or not, Imperion had breached all the rules. “Abase yourself,” Zond said sternly.

Imperion ignored this command, too. Perhaps this was just as well, since the floor of Heaven was awash already, and steaming. Imperion kept his flaming gaze on Zond. “Father! The Sage of Dissolution has been born!”

Читать дальше