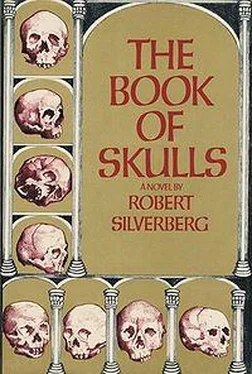

Robert Silverberg - The Book of Skulls

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Silverberg - The Book of Skulls» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1972, ISBN: 1972, Издательство: Charles Scribner's Sons, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Book of Skulls

- Автор:

- Издательство:Charles Scribner's Sons

- Жанр:

- Год:1972

- ISBN:0-684-12590-0

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Book of Skulls: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Book of Skulls»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Book of Skulls — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Book of Skulls», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Aha! The sin of Eli Steinfeld! No trifling sexual peccadillo, no boyhood adventure in buggery or mutual masturbation, no incestuous snuggling with his mildly protesting mother, but rather an intellectual crime, the most damning of all. Little wonder he had held back from admitting it. Now, though, he poured forth the incriminating truth. His father, he said, lunching one afternoon‘ in an Automat on Sixth Avenue, had happened to notice a small, gray, faded man sitting by himself, exploring a thick, unwieldy book. It was an arcane volume on linguistic analysis, Sommerfelt’s Diachrordc and Synchronic Aspects of Language , a title that would have meant nothing whatever to the elder Steinfeld had he not just a short while before forked out $16.50, no trivial sum in that family, to buy a copy for Eli, who felt he could not live much longer without it. The shock of recognition, then, at the sight of that bulky quarto. Upswelling of parental pride: my son the philologist. An introduction follows. Conversation. Immediate rapport; one middle-aged refugee in an Automat has nothing to fear from another. “My son,” says Mr. Steinfeld, “he’s reading that same book!” Expressions of delight. The other is a native of Rumania, formerly professor of linguistics at the University of Cluj; he had fled that land in 1939, hoping to enter Palestine but arriving instead, by a roundabout route through the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Canada, in the United States. Unable to secure an academic appointment anywhere, he lives in quiet poverty on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, holding whatever jobs he can find: dishwasher in a Chinese restaurant, proofreader for a short-lived Rumanian newspaper, mimeograph operator for a displaced-persons information service, and so on. All the while he is diligently preparing his life’s work, a structural and philosophical analysis of the decay of Latin in early medieval times. The manuscript now is virtually complete in Rumanian, he tells Eli’s father, and he has begun the necessary translation into English, but the work goes very slowly for him, since even now he is not at home in English, his head being so thoroughly stuffed with other languages. He dreams of finishing the book, finding a publisher for it, and retiring to Israel on the proceeds. “I should like to meet your boy,” the Rumanian says abruptly. Instant emanations of suspicion from Eli’s father. Is this some kind of pervert? A molester, a fondler? No! This is a decent Jewish man, a scholar, a melamed , a member of the international fellowship of victims; how could he mean any harm to Eli? Telephone numbers are exchanged. A meeting is negotiated. Eli goes to the Rumanian’s apartment: one tiny room, crammed with books, manuscripts, learned periodicals in a dozen languages. Here, read this, the worthy man says, this and this and this, my essays, my theories; and he thrusts papers into Eli’s hands, onionskin sheets closely typed, single spaced, no margins. Eli goes home, he reads, his mind expands. Far out! This little old man has it all together! Inflamed, Eli vows to learn Rumanian, to be his new friend’s amanuensis, to help him translate his masterwork as quickly as possible. Feverishly the two, the boy and the old man, plan collaborations. They build castles in Rumania. Eli, out of his own money, has the manuscripts Xeroxed, so that some goy in the next apartment, falling asleep over a cigarette, does not wipe out this lifetime of scholarship in a mindless conflagration. Every day after school Eli hurries to the little cluttered room. Then one afternoon no one answers his knock. Calamity! The janitor is summoned, grumbling, whiskey-breathed; he uses his master key to open the door; within lies the Rumanian, yellow-faced, stiff. A society of refugees pays for the funeral. A nephew, mysteriously unmentioned previously, materializes and carts off every book, every manuscript, to a fate unknown. Eli is left with the Xeroxes. What now? How can he be the vehicle through which this work is made known to mankind? Ah! The essay contest for the scholarship! He sits possessed at his typewriter, hour after hour. The distinction in his own mind between himself and his departed acquaintance becomes uncertain. They are collaborators now; through me, Eli thinks, this great man speaks from the grave. The essay is finished and there is no doubt in Eli’s mind of its worth; it is plainly a masterpiece. Moreover he has the special pleasure of knowing that he has salvaged the life’s work of an unjustly neglected scholar. He submits the required six copies to the contest committee; in the spring the registered letter comes, notifying him he has won; he is summoned into marble halls to receive a scroll, a check for more money than he can imagine, and the excited congratulations of a panel of distinguished academics. Shortly afterward comes the first request from a professional journal for a contribution. His career is launched. Only later does Eli realize that in his triumphant essay he has, somehow, forgotten entirely to credit the author of the work on which his ideas are based. Not an acknowledgment, not a footnote, not a single citation anywhere.

This error of omission abashes him, but he feels it is too late to remedy the oversight, nor does the giving of proper credit become any easier for him as the months pass, as his essay gets into print, as the scholarly discussion of it begins. He lives in terror of the moment when some elderly Rumanian will arise, clutching a parcel of obscure journals published in prewar Bucharest, and cry out that this impudent young man has shamelessly rifled the thought of his late and distinguished colleague, the unfortunate Dr. Nicolescu. But no accusing Rumanian arises. Years have gone by; the essay is universally accepted as Eli’s own; as the end of his undergraduate days approaches, several major universities vie for the honor of having him do advanced study on their faculty.

And this sordid episode, Eli said in conclusion, could serve as metaphor of his whole intellectual life — all of it face, no depth, the key ideas borrowed. He had gone a long way on a knack for making synthesis masquerade as originality, plus a certain undeniable skill in assimilating the syntax of archaic languages, but he had made no real contribution to mankind’s store of knowledge, none, which at his age would be pardonable had he not fraudulently gained a premature reputation as the most penetrating thinker to enter the field of linguistics since Benjamin Whorf. And what was he, in truth? A golem, a construct, a walking Potemkin Village of philology. Miracles of insight now were expected of him, and what could he give? He had nothing left to offer, he told me bitterly. He had long ago used up the last of the Rumanian’s manuscripts.

A monstrous silence descended. I could not bear to look at him. This had been more than a confession; it had been hara-kiri. Eli had destroyed himself in front of me. I had always been a little suspicious, yes, of Eli’s supposed profundity, for though he undoubtedly had a fine mind his perceptions all struck me in an odd way as having come to him at second hand; yet I had never imagined this of him, this theft, this imposture. What could I say to him now? Cluck my tongue, priestlike, and tell him, Yes, my child, you have sinned grievously? He knew that. Tell him that God would forgive him, for God is love? I didn’t believe that myself. Perhaps I might try a dose of Goethe, saying, Redemption from sin through good works is still available, Eli, go forth and drain marshes and build hospitals and write some brilliant essays that aren’t stolen and all will be well for you. He sat there, waiting for absolution, waiting for The Word that would lift the yoke from him. His face was blank, his eyes devastated. I wished he had confessed some meaningless fleshly sin. Oliver had plugged his playmate, nothing more, a sin that to me was no sin at all, only jolly good fun; Oliver’s anguish thus was unreal, a product of the conflict between his body’s natural desires and the conditioning society had imposed. In the Athens of Pericles he would have had nothing to confess. Timothy’s sin, whatever it was, had surely been something equally shallow, sprouting not from moral absolutes but from local tribal taboos: perhaps he had slept with a serving wench, perhaps he had spied on his parents’ copulations. My own was a more complex transgression, for I had taken joy in the doom of others, I perhaps had even engineered the doom of others, but even that was a subtle Jamesian sort of thing, in the last analysis fairly insubstantial. Not this. If plagiarism lay at the core of Eli’s glittering scholastic attainments, then nothing lay at the core of Eli: he was hollow, he was empty, and what absolution could anyone offer him for that? Well, Eli had had his cop-out earlier in the evening, and now I had mine. I rose, I went to him, I took his hands in mine and lifted him to his feet, and I said magic words to him: contrition, atonement, forgiveness, redemption . Strive ever toward the light, Eli. No soul is damned for all eternity. Work hard, apply yourself, persevere, seek self-understanding, and there will be divine mercy for you, because your weakness comes from Him and He will not chastise you for it if you show Him you are able to transcend it. He nodded remotely and left me. I thought of the Ninth Mystery and wondered if I would ever see him again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Book of Skulls»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Book of Skulls» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Book of Skulls» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.